http://dx.doi.org/10.19183/how.22.2.141

Creativity in the English Class: Activities to Promote EFL Learning

Creatividad en la clase de inglés: actividades que promueven el aprendizaje del inglés como lengua extranjera

Hernán A. Avila

nitpicker12@hotmail.com

Universidad del Cauca, Popayán, Colombia

Received: July 7, 2015. Accepted: August 31, 2015.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Avila, H. A. (2015). Creativity in the English class: Activities to promote EFL learning. HOW, 22(2), 91-103. http://dx.doi.org/10.19183/how.22.2.141.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. License Deed can be consulted at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This article introduces a pedagogical intervention that includes a set of creative activities designed to improve the oral and written production of students in the English classroom, especially those who have shown a lack of interest or attention. It was observed that participants initially seemed careless about studying the language. Eventually they responded to the proposed methods positively and were more willing and motivated to participate in chain games, creative writing, and screenwriting exercises. The activities helped develop the students’ fluency in both oral and written production and improved their understanding of English grammar and structure.

Key words: Activities, creativity, teaching, English, strategies.

Este artículo presenta una intervención pedagógica que incluye un conjunto de actividades creativas diseñadas para mejorar la producción oral y escrita de los estudiantes en el aula de inglés, especialmente en aquellos que han demostrado una falta de interés o atención. Se observó que los participantes inicialmente parecían desinteresados en el idioma. Finalmente, los pupilos respondieron a los métodos propuestos positivamente y estaban más dispuestos y motivados a participar en juegos de cadena, ejercicios de escritura creativa y guiones cinematográficos. Las actividades con tribuyeron a desarrollar la fluidez de los estudiantes en la producción oral y escrita demostrando fortalezas en la comprensión gramatical y estructural del idioma inglés.

Palabras clave: actividades, creatividad, enseñanza, estrategias, inglés.

Introduction

Just as writers face writer’s block and comedians “die” on stage, teachers can expect to confront moments when a crippling lack of classroom interest or general lack of attention threatens to throw the learning process off course. In order to enhance the performance of English as a foreign language (EFL) for teachers faced with such a situation, creative activities that were regarded as useful were collected in this pedagogical reflection.

Being an English teacher is indeed a challenge to take on in any educational context. When I was a novice teacher, I struggled to design activities that were both enjoyable and fruitful and that fully engaged my students’ creativity. For this reason, I implemented several strategies such as creative writing exercises as well as oral interaction activities that demanded a greater degree of creativity to reinforce the quality of teaching. Such creative activities will be presented in this text since they were used in order to stimulate learning and developing a more appropriate foreign language experience.

There is a need to be aware of innovative and powerful strategies for the improvement of learning a foreign language in an academic setting. In order to be fully prepared and confident in the classroom, teacher-researchers should look for what is suitable in their particular educational context. Educators should consider potential and creative teaching options to overcome students’ learning challenges such as their lack of interest and attention in the subject.

I start by presenting an assortment of theories based on creativity and its usefulness in developing the instructional strategies. Then, I describe the setting and the participants. In addition to that, I include the methodology as well as the description and reflection obtained in the process and, finally, I put forward the respective conclusions.

Teachers take on a role of authority in the eyes of the students, which greatly influences pupils’ learning process (Burns & Richards, 2009). In my view, teaching is quite a demanding job that requires expertise and thorough knowledge of different activities to win students over. When starting out as a teacher, it is common to feel lost and nervous; however, I did not let it discourage me. For this reason, I used my creativity to its maximum potential to engage in appropriate activities and carry out helpful strategies.

My instructional activities are meant to help teachers increase their effectiveness as they make the transition from being a college language student into this phase of their teaching career. As teachers, we have to be aware that our pupils are promised a well-rounded education in the English field, which covers the four skills: reading, writing, speaking, and listening. Therefore, teachers are meant to let students receive the full spectrum of the language benefits emphasizing approaches that could help students learn in a creative, innovative way.

In my teaching career, I have observed that pupils are usually taught with a traditional method where the teacher uses a marker and writes the lesson on the board. In regard to that tradition, I stress that fact that educators have to be quite prepared to teach, rather than just cover the units of an English book with its requirements. It is important for teachers to give students a sense of what to expect in the course while making the class fun, entertaining, and beneficial for the learners.

Throughout this article, I intend to provide helpful strategies, which instructors may rely on to use in the classroom where they will be teaching. By sharing the activities I propose in this pedagogical experience, I expect students to find them fruitful and consequently educators may practice them in their educational context.

I also intend to share the activities since I want to strengthen English teachers’ views on how to carry out their tasks in a more innovative, creative way, distancing themselves, if possible, from just explaining on the board or following a grammar book. Having different activities near at hand will probably benefit teachers while they embark on this difficult, but rewarding task, especially those practitioners who will be confronting several students to please.

In order to present the most suitable activities that I have collected throughout my experience as an educator, I will discuss the theory I found to be most pertinent for the development of these instructional strategies.

Theoretical Framework

In order to solve problems and have innovative activities to reach out to students, one has to be creative. Naiman (1998) states that creativity is the process of turning imaginative ideas into reality. For this author, creativity involves two processes: thinking, then producing; and adds that innovation is the production or implementation of an idea. If teachers have ideas, but do not act on them, they are imaginative but not creative. It is noteworthy that any idea should be used in an educational context to see if it works or if it does not.

Lannon (2000) agrees with the previous statements, arguing that being a teacher requires a lot of thinking, especially when students are not showing the expected results. For this reason, several of the activities I gathered were created based on the participants’ needs, so that they could be more engaged in the classes. I, on the other hand, would disagree with Naiman’s description of the process as “thinking and then producing.” To complement that statement, I think that when we are done producing we have to be thinking again to see what worked and what did not work to realize what needs to be changed. So we start by thinking and also end up thinking about the results we observe.

According to May (1994) creativity is the process of bringing something new to the culture and requires passion and commitment. This brings to our awareness what was previously hidden and helps us gain new points of view. May even regards the experience of creativity as one of “heightened consciousness ecstasy.” Based on May’s statement, I highlight the fact that when we are in a classroom, we become aware of our previous knowledge and use it with our new knowledge, creating and innovating based on what we observe, develop, and reflect upon.

Burns and Richards (2009) assert that our contribution to education is to enhance student-teachers’ knowledge growth providing them with opportunities to make their preexisting knowledge explicit to be examined and challenged. Therefore as teachers, we must use whatever we can get our hands on to evaluate students’ performances in order to achieve success in the classroom.

In order to improve the instructional practices in my context, I did a lot of reading as to what strategies would work best for the aspects I observed and analyzed in my setting. Vecino (2007) tackles creativity in one of the skills of the language with an appealing strategy. The author suggests creative writing as a research tool to improve students’ feelings towards writing. I thought I could go in the same direction to try to improve the way creativity was used in my teaching context.

The above statements could be related to Pardlow’s (2003) view on creative writing. The author states that with the specialized techniques of creative writing, it was easier to teach the writing process and the students did not experience any writer’s block when the writing was creative. Amado (2010) contends that creative writing methods enabled students “to pour out words, open the gate of imagination, gain understanding of accuracy, and most importantly, experience the sheer joy of [learning a foreign language]” (p. 163).

In Csikszentmihalyi’s (2013) view, the components of creativity include domains, fields, and people. A domain is defined as a set of symbolic rules and procedures. A field includes all the individuals who act as gatekeepers for the domain. I would agree with the author since creativity is achieved when a person using the symbols of a given domain-like language has a new idea or sees a new pattern. Thus, educators can build a repertoire of strategies carried out to spark a novelty in the English language domain and bring out a spirit of creativity in the foreign language field. Therefore, creativity is expanded to its fullest potential.

In order to have an in-depth understanding of the creativity term, Csikszentmihalyi (2013) describes five steps to achieve creativity:

Preparation: Arousing curiosity of a problematic situation.

Incubation: Ideas fly below the threshold of consciousness.

Insight: The moment when the puzzle starts to fall together.

Evaluation: Deciding if the insight is valuable and worth pursuing.

Elaboration: Translating the insight into its final work. (p. 79)

These steps are brought up when teachers use their minds to create something, in this case an activity to make the most of in class. The whole creativity process engages teachers to show something innovative and imaginative that is worth researching. After analyzing the authors’ views, I see creativity in teachers as essential to create suitable activities to motivate learners and encourage their progress.

Setting and Participants

This pedagogical intervention was carried out in a Colombian private English-teaching institute.1 This institute offers several personalized English programs aimed at learners from diverse backgrounds as well as students of all ages who want to perfect their English or live abroad. This school focuses on innovative, cost-effective solutions for English learners. The aim of this English school is to be a recognized school, known internationally by remaining committed to learners with fresh ideas and professional experience.

Personalized courses are a priority since students’ performances are thoroughly analyzed and assessed according to their needs. Courses are usually made up of 10 to 20 people at the most to help students on a personal basis. Eleven participants—young adults from 20 to 25 years old—agreed to be a part of this pedagogical intervention after they were explained how effective the use of creativity may be in an educational setting. Students were at an intermediate level in the English language.

Teaching Frame

Seeking to adapt the best methodology for my purposes, I needed to have a grasp of the course content as well as access to all necessary materials, including screenplays, creative writing exercises, and other resources. I intended not to go over the same content that students were learning. I took a broader view, considering the ideas and assumptions behind the content and anticipating topics that students would be studying.

I systematized this pedagogical experience by following the tenets of action research, an approach that could be a huge step toward making the positive changes in the English class that my creative activities are meant to achieve. This process is related to Carr and Kemmis (1986), who contend that action research helps teachers make changes in carrying out their classroom practices and in planning, implementing, and evaluating them. My activities are intended to be implemented and reflected upon according to the data gathered from participants.

Kemmis and McTaggart (1988) add that action research means to plan, act, observe, and reflect more carefully, more systematically, and more rigorously than one usually does in everyday life. Though I present this article as a pedagogical experience, I see action research as paramount in systematically collecting the data that help me organize my thoughts in planning and carrying out classroom activities. In the last fifteen years, teachers and educators have increasingly relied on action research methodology to collect reliable data and provide valuable insights to classroom teachers, and it has proven to be an excellent source of archival data (Zuber-Skerritt, 1991).

In carrying out classroom activities, I used Elliot’s (1991) action model, in which the teacher plans, acts, observes, and reflects upon the pedagogical experience. This cycle includes the planning of exercises and pertinent observation as the teacher helps students improve their oral and written production skills and increases their motivation to learn. Observing, acting, and reflecting on these activities create a proper space for a pedagogical experience to take place and for students to communicate their feelings and enhance their abilities in the target language.

Several activities were planned according to the time I had with the participants. The purpose was to introduce students to creative methods supported by theory. In the workshops carried out in this teaching experience, students found exercises that led their language skills in various directions, as well as strategic steps with which to use their knowledge. Besides that, students found techniques to support their views in order to have a solid foundation in their foreign language practice.

The exercises were created to let students write/speak with focus and direction, to develop their ideas and descriptions, to discover their voices, and to apply grammar rules in a fun way. I consider my activities such as chain games and teamwork to comprise a great space for students to communicate their feelings through exercises so as to develop their thinking and enhance their abilities in the target language. My intention was to design activities that offered students the opportunity to communicate their feelings, develop their thinking, and enhance their abilities in the target language. Thus, participants were given an opportunity to develop their creative potential and to synthesize and apply knowledge and skills by creating and participating in the teaching process.

Description of the Activities

In this section, I describe nine activities and their positive impact on the students’ learning process. Participants are labeled using letters (e.g., Student A). All of the activities are listed one by one and are arranged in order of complexity. I followed a systematic process with each one of the exercises and strategies enhancing the four abilities, which are writing, speaking, listening, and reading.

Activity 1: Remembering English Grammar and Structures

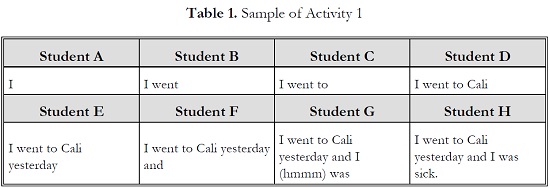

In this activity, I asked students to sit in a semicircle. Each student had to say a word, one by one, following the structure of the previous word already mentioned. For example, Student A would say “I,” or “you,” or “he.” Then, Student B would continue with another word following the structure of the word Student A mentioned. For example, Student B would say “I went,” because students would already know that a personal pronoun is usually followed by a verb. Student C would follow through with the third word: “I went to,” and so on. Consequently, students would remember grammar and structures in the language and they would be listening to their peers (See Table 1).

This activity proved to be quite beneficial because students did not only remember grammar, but had the opportunity to test their memory skills. They also interacted together hearing their peers’ voices. Students were more encouraged to get points or not to be penalized doing something funny in front of the other students. I would strongly advise teachers to use this chain game to reinforce grammar as well as structures in the English language.

Activity 2: Creating a Fictional Story

In this activity students sat again in a semicircle. In this case, however, the procedure was more complex than Activity 1 because, instead of a word, each student had to say a complete sentence. Students tried to make the emerging story as coherent as possible as can be seen below:

Student A: Pepito went to school.

Student B: Pepito went to school and he had a bike accident.

Student C: It was very serious; his leg was bleeding (new word).

Student D: He called his mother.

Student E: His mother fainted (new word).

While students made up their story, I, as a guide, encouraged them to use the dictionary and assisted them along the process. All students participated and were quite creative. Students helped one another, participating more fully, and were not as quiet as they were at the beginning. So first time-teachers can benefit greatly from these kinds of activities where there is teamwork and all pupils participate, working on grammar while creating their own stories.

Activity 3: Promoting Creative Writing

In this activity, students were divided into two groups. Both groups had to sit in a semicircle and were given a sheet of paper that said: “It was dark and stormy.” Then, students in both groups had three minutes to write a story and then hand it to their partners to continue writing about the same subject and complete the story. The group who had the best story with the best grammar and content would get points.

I realized that students wrote freely and with great skill and self-assurance. Pupils prepared their characters already determining their physical, emotional features and traits, incubating ideas, evaluating and elaborating the development of the story with the description of the place and locations. Both groups allowed their creativity to fly and imagine what it was like to write their stories in groups, creating their own world of fiction.

These teaching strategies give informative and emotional structure where grammar is a natural way of expressing ideas. I realize that activities like these not only promote teamwork and peer editing, but also give students liberty of expression, interest, and purpose in the course of work. Every story had the proper structures, so exercises can be built according to a principle of developing writing skills.

Activity 4: Boosting Vocabulary Through Screenwriting

Instead of writing essays or short texts, I decided to expand on my previous work (Amado, 2010) to boost students’ vocabulary as well as to develop their writing skills with screenwriting. According to Argentini (1998), screenwriting is a document that outlines every aural, visual, behavioral, and lingual element required to tell a story. The way students visualize the story they want to write, based on their experience or their imagination, is relevant in the process of acquiring smoothness in writing.

With this form of creative writing, Al-Alami (2013) suggests that students start with the creation of an idea; then the student fleshes out that idea into actions, dialogue, characters, and scenes. Would it not be positive if students had an idea, and from that simple idea, wrote more pages? With screenwriting, students visualize a story, and they can turn a simple sentence or idea into a properly formatted screenplay.

In order to practice screenwriting in class, I allowed students to see a movie and then read three scenes of the screenplay. They had to underline or circle unknown vocabulary. They could infer the new vocabulary they learned because they had previously watched the movie. The words they underlined were cohesive devices and unknown words such as clockwise direction, nun, chapel, whispering, kneeling, lights in the windows flick on, stretcher, pulls up in BMW, moves off, among others. These are just some of the words that could evidence how much vocabulary students learned when watching the movie and inferring what those words meant.

Pupils learned grammar and my corrections as well. Some of the comments the students made were: “It was great to watch a film and then read some of the scenes;” “I had never read the screenplay of a movie;” “I didn’t know many of the words, but I could infer them easily since I saw the film and the scenes of the screenplay were my favorite.” All these comments motivated students to go on reading scripts instead of the usual texts teachers give students such as essays, worksheets, and so on.

Activity 5: Sharing a Speech

I would also suggest writing and sharing a speech about any topic students want to share. In this strategy, for a speech, students could use whatever they wanted to say. Students were given 20 minutes to write their speech. They were free to use their own knowledge or what was easy for them. They chose interesting speeches such as personal information about their lives, family, love life, problems, favorite movie, their best or worst experience, and so forth.

With this activity, teachers get the chance not only to see students’ limitations language-wise, but they get to know what the students are like, building rapport with and among them. The way students give and share their speech will be influenced by experiences from the past, expectations for the future and will contribute to teachers’ practices (Kelchtermans, 2009).

Activity 6: Circles of Life

In order to listen to what students have to say and share I proposed a very interesting activity that enabled me to get excellent results. I asked students to draw three big circles. In the circles, they had to write about the most significant aspect of their lives. For example in Circle 1, they had to write the most meaningful number for them; in Circle 2, the object they could not live without; in Circle 3, the most important name for them.

Students were told to stand up and walk around the classroom sharing every circle with the other students. For instance, as shown in Figure 1, Student A shared with his classmates that 2 was his most significant number because he had two children. He went on to elaborate more on his life and how proud he was of his children. Then, he made sure others knew that reading books was his passion. He proudly added that Andrea is his wife, giving personal details about her.

This technique, although quite simple, was very effective because students interacted with one another, listening to what the other had to say. A friendship could be formed this way and they practiced their oral skills as well. Besides that, telling this in circles is appealing and creative instead of just writing information in the notebook.

Activity 7: Drawing and Speaking

I used another student activity that was new to this specific group. In order to practice speaking, I asked students to draw something they wanted to share. They had to draw it on the board and explain why it was drawn. After that, another student would come up and draw another object or person next to it. After all the participants drew their objects, they would have to create a story based on the drawings on the board.

Students had the opportunity to share their stories with others and evaluate their own process with peer feedback. I understood that students welcomed the activity with a wide array of emotions. First of all, they seemed to be willing to create, draw, and speak. They claimed more autonomy in their own drawings and gained confidence while speaking to their peers.

One of the students drew a guitar, the other a rabbit. Another drew the teacher, just to name a few. Students had the challenge to create a story with those drawings, which proved to be funny and at the same time quite beneficial for their skills. Besides that, they got to know more about their classmates’ personalities.

Activity 8: Asking and Answering Questions

I asked students to write as many questions as they could in 15 minutes about anything they wanted. I told them to be careful about grammar and the structures for asking a question. After students were done with the questions, each one of them had to come up front and sit in a chair while the other classmates asked them the questions they wrote.

This exercise proved to be very beneficial because students could learn the structures of questions in the English language. The class was very active since all students participated and they asked each one of their peers interesting questions which enabled students to be more prepared for interviews in the future.

Activity 9: Students’ Autonomy in Creating Their Own Activities

The best technique, in my opinion, to win students over is certainly to let them do their own activities. After I proposed many of the activities I did, I thought perhaps they could just do the same. I told them to get into groups and prepare their own fun and fruitful activities for their peers.

Most of the students used fun and comprehensible activities such as guessing games, looking for objects in the classroom to learn prepositions, minimal pairs with appealing visual aids, broken telephone, crossword puzzles, going outside the classroom to compete in relay races, etc. When students created their own games and proposed them to the class, I could see they were more involved and the class was much more motivating than it was before. Therefore, pupils’ autonomy was paramount in foreign language achievement.

Conclusions

By stimulating creative strategies in the classroom, I ensured English learning had a purpose in every activity. I was able to expand my knowledge with the students’ contributions and learned that these activities have helped participants to expand their creativity. Hence, these techniques could surely be repeated in any group of students the teacher will be confronting.

With the instructional use of creativity in the English class, many insightful, accessible activities emerged and I could observe that pupils experienced new learning techniques to tell more about themselves. Participants at first were reluctant to participate, but later responded positively to the methods. The classes and the students’ contributions provided for a vivid and imaginative experience. They also were a challenge, confronting students with the need to follow English language rules.

When carrying out this pedagogical intervention, students followed a systematic process from activity to activity that allowed for clarity and better organization. From starting with a simple creative exercise like the chain game, participants ended up giving their own speech and creating their own activities as well, based on the theory previously given. Teaching systematically provides participants with better tools for their final products.

English teachers can use their creativity to make classes much more original, and go outside the formal bonds of teaching. There are many more methods, exercises, and activities to explore and teach. For this reason, teachers need to expand their horizons in an EFL context to see what will probably be efficient for future generations.

1The name of the institute is kept confidential to maintain the anonymity of the participants.

References

Al-Alami, S. (2013). Utilising fiction to promote English language acquisition. Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Amado, H. (2010). Screenwriting: A strategy for the improvement of writing instructional practices. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 12(2), 153-164.

Argentini, P. (1998). Elements of style for screenwriters: The essential manual for writers of screenplays. Boulder, CO. Lone Eagle Press.

Burns, A., & Richards, J. C. (2009). The Cambridge guide to second language teacher education. Cambridge, UK. Cambridge University Press.

Carr, W., & Kemmis, S. (1986). Becoming critical: Education, knowledge and action research. Melbourne, AU: Deakin University Press.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2013). Creativity: The psychology of discovery and invention. New York, NY: Harper Perennial.

Elliott, J. (1991). Action research for educational change. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

Kelchtermans, G. (2009). Who I am in how I teach is the message: Self-understanding, vulnerability, and reflection. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 15(2), 257-272. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13540600902875332.

Kemmis, S., & McTaggart, R. (1988). The action research planner (3rd ed.). Geelong, AU: Deakin University Press.

Lannon, J. M. (2000). The writing process: A concise rhetoric and reader (9th ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

May, R. (1994). The courage to create. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

Naiman, L. (1998). Fostering innovation in an IT world. Canadian Information Processing Society Journal.

Pardlow, D. (2003, March). Finding new voices: Notes from a descriptive study of how and why I learned to use creative writing pedagogy to empower my composition students and myself. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Conference on College Composition and Communication, New York, NY. Retrieved from ERIC database. (ED474934)

Vecino, A. M. (2007). Exploring the wonder of creative writing in two EFL writers. (Master’s thesis). Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas, Bogotá.

Zuber-Skerritt, O. (Ed.). (1991). Action research for change and development. Aldershot, UK: Gower.

The Author

Hernán A. Avila holds a Master’s degree in Applied Linguistics to the teaching of English from Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas, Colombia. His research interests include the improvement of instructional strategies for educators.