http://dx.doi.org/10.19183/how.23.2.267

Collaborative Work and Language Learners’ Identities When Editing Academic Texts

Trabajo colaborativo e identidades de aprendices de lenguas al editar textos académicos

Lorena Caviedesa

Angélica Mezab

Ingrid Rodríguezc

aUniversidad El Bosque, Bogotá, Colombia. E-mail: caviedeslorena@unbosque.edu.co.

bUniversidad El Bosque, Bogotá, Colombia. E-mail: mezamaria@unbosque.edu.co.

cUniversidad El Bosque, Bogotá, Colombia. E-mail: rodriguezingrid@unbosque.edu.co.

Received: January 15, 2016. Accepted: April 6, 2016.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Caviedes, L., Meza, A., & Rodríguez, I. (2016). Collaborative work and language learners’ identities when editing

academic texts. HOW, 23(2), 58-74. http://dx.doi.org/10.19183/how.23.2.267.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. License Deed can be consulted at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This paper presents a qualitative case study that involved three groups of English as a foreign language pre-service teachers at a Colombian private university. Each group attended tutoring sessions during an academic semester. Along these sessions, students were asked to work collaboratively in the editing process of some chapters of their thesis project through a corpus interface. Students wrote journals and participated in interviews about their experiences. Teachers also wrote journal entries to describe and interpret their observations from the meetings. Findings reveal the participants’ identities that emerged from their group dynamics and their insights about their collaborative process when editing academic texts.

Key words: Collaborative work, editing process, learners’ identities.

Este artículo presenta un estudio de caso cualitativo con tres grupos de estudiantes de licenciatura en educación bilingüe de una universidad privada en Colombia. A cada grupo se le asignó un tutor durante un semestre y se le solicitó trabajo colaborativo para la edición de un proyecto de grado usando un corpus. Los estudiantes escribieron diarios y participaron en entrevistas sobre su experiencia, mientras que los docentes escribieron diarios para describir e interpretar sus observaciones del proceso. Los resultados develaron las identidades de los estudiantes que emergieron a partir de su dinámica de grupo y sus percepciones del proceso de edición de manera colaborativa.

Palabras clave: identidades de los estudiantes, proceso de edición, trabajo colaborativo.

Introduction

Academic writing represents a challenge for writers since it requires certain vocabulary and a number of structures that show what they can do with the academic discourse as part of different disciplinary communities (Wolsey, Lapp, & Fisher, 2012). It involves multiple participants in a single writing project (Galegher & Kraut, 1994) since it is important for the writers to receive feedback from their audience in order to improve their production. Hence, the writing of academic texts can be enriched through collaborative processes as it offers students the opportunity to be part of a community through their texts and to support each other (Hirvela, 1999).

Using collaborative writing for the production of academic texts is based on the idea that co-authorship allows English as a foreign language (EFL) students to observe their partners’ cognitive processes and strategies in order to develop a single topic (Daiute, 1986). At the same time, it provides them with the opportunity to act as editors of their texts (Storch, 2005).

Taking into account the information shared above, we decided to follow 10th semester students’ editing process of their research reports in order to find some aspects that required improvement in terms of collaborative writing and group work. Throughout a series of observations held in a private university’s EFL teaching program, we were able to notice that students’ academic production presented inaccurate uses of English vocabulary, grammar structures, and mechanics; which made their texts difficult to understand.

Additionally, when students were assigned to edit texts collaboratively, they could not reach a general agreement, so they just divided the sections to be edited, making the final version of the manuscript incoherent and with different styles and proficiency levels.

This article therefore explores collaborative work of pre-service EFL teachers from a private university to help them throughout the editing processes of an academic manuscript. It also explores the language learner identities that emerged from this experience. We decided to use a corpus interface as a tool that allows students to find linguistic patterns of authentic uses of English in different contexts. In this article, we present first definitions of constructs we consider to be key in the development of our research process. Then we share our research design, the results we obtained from the students’ and the teachers’ insights about collaborative work, and the conclusions gathered from our research experience.

Literature Review

Along the different observations we made during our students’ editing process, we noticed three areas that caught our attention. The first aspect was related to the way students worked as part of a group in order to edit their manuscripts; the second aspect was the way the editing process was developed in groups; and the third one was related to students’ identities as members of a team. Taking these observations as a starting point, we decided to work on four main constructs: collaborative work and collaborative writing, which gave us insight about the process that a group would carry out as editor of a single text; academic writing, which is relevant since students were expected to follow the standards of writing an academic text, so they would require a supportive academic community to receive feedback; and the relation between identities and language learning, which would inform us about the positioning process of students inside an academic group as a social community.

Collaborative Work

Collaborative work fosters the generation of knowledge inside an academic community. It differs from cooperative work in its epistemological nature, which is oriented towards acculturation and negotiation processes, since it is not focused on highly organized processes and techniques. While cooperative work is prescriptive, collaborative work attempts to promote knowledge in less traditional ways (Oxford, 1997).

Authors such as Vygotsky (1978) and Dewey (1938) focused on the importance of academic communities in the learning processes. Dewey establishes the necessity to promote a close relationship among the individuals, their community and the world, to socially construct their ideas. Moreover, Vygotsky states that communication as a social practice allows cognitive development in the participants of a community. Thus, individuals develop their potential when they are part of a collectivity. It is important formembers of a community to allow the negotiation of their ideas, roles, arguments, and strategies in order to create inclusive environments where everyone helps to construct knowledge and identities (César & Santos, 2006).

Collaborative Writing

Collaborative writing is a social practice that interprets and responds to other texts through the construction of collective discourses mediated by progressive and dynamic discussions and negotiations (Hirvela, 1999). These processes encourage students to work as a team, learning from one another and generating one text together. Participants of a collaborative writing group become, on the one hand, genuine readers of their peers; whereas, on the other hand, they also become critical writers by being aware of the needs and characteristics of their audience. Collaborative writing promotes the development of writing skills through the construction of different drafts and versions that will allow the production of an improved, edited final text (Oshima & Hogue, 1999).

Yate González, Saenz, Bermeo, and Castañeda Chaves (2013) identified the need to foster solid linguistic foundations in order for their students to write properly. Hence, they implemented collaborative work and writing, so that their students would be able to create environments where they would help each other to construct meaning and knowledge in their EFL classes.

Academic Writing

Academic writing differs from other writing processes because it is neither anecdotic nor personal. It requires more elaborated texts that abide by the standards and conventions of an academic community (Lewin, Fine, & Young, 2001). This type of text should have coherence, cohesion, organization, and fluency in order to accomplish its rhetorical goal.

These texts also require the elaboration of different drafts and versions; therefore, it is important to create communities where the participants can become both readers and writers. Zúñiga and Macías (2006) decided to offer their students tools to provide feedback on their peers’ texts. Hence, the advantage of receiving and providing feedback and the interpersonal commitment that such processes entail would be made evident.

Identity and Language Learning

Norton (1997) states that the term identity refers to the way “people understand their relationship to the world, how that relationship is constructed through time and space, and how people understand their possibilities for the future” (p. 410). Drawing on Halliday’s sociocultural theory of language (1985) and Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory of mind (1978), people can only create this relationship with the outer world through language and the way they use it to position themselves before others through their subjectivity. Weedon (1987) defines subjectivity as the “conscious or unconscious thoughts and emotions of the individuals, and their sense of themselves and their ways of understanding their relation with the world” (p. 32). In other words, people shape their relationship with the world and the use they give to language according to the context they are part of and the needs they have for positioning themselves.

Over the last years, the relationship between identity and language learning has taken an important role in the analysis of learning processes, particularly because speakers are constantly “organizing a sense of who they are and how they relate to the social world” (Norton, 1997, p. 410), and the way they tend to follow this process is through their discourse. Since classrooms and educational contexts give rise to societal practices and interactions (Toohey, 1998), they tend to exhibit and generate social structures that can determine the way students and teachers see themselves and are seen by others inside a given context.

Research Design

Since the main objective of the research is to analyze language learners’ identities that emerge when working collaboratively, the study was based upon a qualitative paradigm. The main goal of qualitative research is to “offer descriptions, interpretations and clarifications of naturalistic social contexts” (Burns, 1999, p. 22). It draws from data collected from teachers and students’ journals and interview transcripts that allowed us to interpret human behavior within a specific research context (Saldaña, 2011).

Additionally, the study is catalogued as a case study. It allows us to establish relations, draw upon conclusions from the gathered information, and understand the participants’ perceptions and worldviews (Thacher, 2006). It also enables us to identify the characteristics of a particular entity, phenomenon, or person.

Setting and Participants

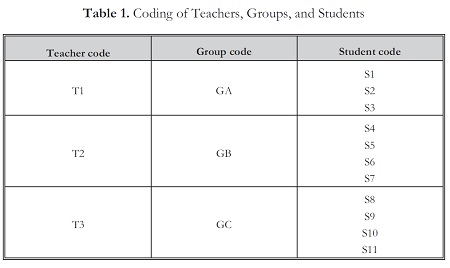

This study took place in a Colombian private university. It was applied to a group of 10th semester students studying in a bachelor in bilingual education program. The participants were 11 students divided into three groups; they had already finished all their English courses and were in the process of editing their final research reports they were asked to present in order to graduate. The participants in the study were coded as shown in Table 1.

Method

During the implementation of the project, each researcher was in charge of a single group and each group handed in a first version of the manuscript to be edited. We proceeded to write our comments and make suggestions for changes in the texts in terms of grammar, vocabulary, and mechanics. Afterwards, students were asked to attend tutoring sessions to work on the use of a corpus interface and the editing process of their reports.

These tutoring sessions were thought out to guide students through the editing process of their manuscripts. We decided to use the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA) as a tool, since it offers a structural analysis of linguistic patterns used in situ (Biber, Conrad, & Reppen, 1998). Both students and teachers wrote their personal reflections regarding collaborative work, the use of corpus, and the different interactions students had inside each group. In the final session, students participated in an interview about their experience working collaboratively to edit their texts.

Instruments, Techniques, and Procedures for Data Collection

Students’ journals. Through these journals we asked our students to provide insights about what they had done to edit their manuscripts, what they had learnt while doing so, and their personal reactions towards the editing process and the use of a corpus.

Teachers’ journals. These journals included the researchers’ observations and perceptions about the students’ collaborative work, their editing process by using a corpus interface, and the identities that emerged inside the groups.

Interviews. The interviews let us know the students’ perceptions about collaborative writing, the process they went through when editing their manuscripts and the use they made of a corpus.

Data Analysis

The data we collected were analyzed through methodological triangulation of the sources. The analysis followed the processes of the grounded theory approach, since this perspective makes researchers immerse themselves into the real world to come up with findings that are grounded in the empirical world (Patton, 1990). Thus, the grounded theory approach focuses on generating theory instead of reproducing a particular theoretical content. Table 2 shows the research inquiries and the headings of the sections of this data analysis.

Emerging Identities When Working Collaboratively

The interviews and journals carried out allowed us to observe the different identities that emerged along the process. Since students’ groups interacted as a social community, their interactions are catalogued as social practices. From this perspective, Norton’s (1997) notion of identity as quoted above is the most suitable to the analysis.

The following subcategories display a series of descriptions corresponding to the students’ identities according to their behavioral patterns throughout the process. It is important to keep in mind that the different names given to the identities in this research follow a literal description of students’ attitudes and behaviors. That is, they are just a tool for cataloguing. All in all, we consider that identities are an intricate social construct that goes beyond cataloguing students (or any person for that matter) as “good” or “bad”.

The overconfident learners. The students catalogued as “overconfident learners” show a very particular set of attitudes during the sessions. These students did not show any interest at all regarding the editing process, and actually made it clear that they were able to edit their texts without any extra help, especially the use of corpus, since they considered it too time consuming. There was one participant who presented this identity in each group (S3, S4, and S8).

S3 found [the interface] difficult and he didn’t seem willing to participate in the tutoring sessions as well as when working on the interface. He usually tapped his feet as if he wanted to finish quickly. (T1, Journal 1)

The three students showed similar behavior during the first tutoring session. S3 and S4 sat far from the group and did not participate actively. They just listened to the suggestions given, but did not interact. S3 and S8 started to tap their feet as if they wanted to finish the activity quickly. The three teachers interpreted their reluctance to learn about the interface as a lack of interest towards the process they were about to start. Additionally, students’ journals stated that the interface was not necessarily useful, and it was very difficult to use, which did not deserve their effort. They seemed to be able to correct their manuscript without using the tool:

S8 mentioned that [COCA] was useful, but he did not use it so much as he had the knowledge of the language that was required to make the corrections on his own. (T3, Journal 6)

Along the sessions, S3 and S4 started progressively to interact with their group when correcting and answering questions by using the corpus and their own knowledge of the language, thus being more involved. However, they explained the interface was time-consuming and difficult to use:

[S3’s] attitude towards the edition process using corpus changed in the last session. Although he insisted on the fact that they were overwhelmed with the amount of work, and he did not want to spend so much time in the edition of the manuscript using a corpus, he accepted that the corpus was useful. (T1, Journal 6)

In contrast, S8 did not attend the following three sessions but kept working on his own to implement the corrections suggested; it was just during the last two sessions that he had met the teacher. Since he was not able to implement the changes required in the manuscript on his own, he thought the corpus would be helpful:

S8 came to the tutoring session and posed some questions about the use and functions of the interface. There were some corrections he couldn’t make, so now he was interested in using the corpus to edit the text. (T3, Journal 5)

As evidenced above, there were two aspects that helped the researchers to categorize some students as “overconfident”. At first, they did not think the corpus interface was useful enough, which at the beginning made them reluctant to participate in the training process to use it, particularly because they considered they had the knowledge to do the corrections suggested without using the corpus as a tool. However, they progressively changed their mind about the corpus and used it when their knowledge was not enough.

The empowered learners. GA and GB presented students who improved their performance progressively as active editors by working collaboratively and using the corpus. S1 and S6 did not seem to be confident in the first sessions; however, their group dynamics and their own interest in the use of the interface made them participate more and feel capable of making decisions in the editing process.

At the beginning of the semester, S1 was perceived as a reserved person who did not participate very often in the tutoring sessions; as a consequence, T1 had to elicit answers from her most of the time. Furthermore, this participant had a lower English proficiency level in comparison to her fellow classmates and displayed a lack of confidence in their tutorials:

She was quiet and shy during her first meeting. When she spoke, it was possible to notice she was less proficient in English, as compared to her partners as she made several mistakes. (T1, Journal 1)

T1 was concerned about S1’s insecurity; however, this participant began to change her attitude in the third session by participating more and showing a better use of the corpus interface. By the end of the semester, S1 was the student who showed more interest in the corpus; in fact, she was the participant who proved a better command of it to edit the manuscript in GA. Additionally, S1 participated more actively in comparison to the first tutoring sessions; thus, she was able to provide explanations and concerns about the corrections and her experience with the corpus:

S1 was the most motivated as she seemed to explain more about the way they had corrected the text by using a corpus . . . she mentioned the functions of the interface and the types of corrections they had implemented. (T1, Journal 5)

Likewise, when the process began, S6 seemed to be afraid of speaking. She kept quiet and waited for her partners to explain what was required when a question was posed. She often looked at her partners nervously and seemed to be too hesitant to speak. Besides, when T2 asked her directly, S6 demonstrated a low English proficiency, which prevented her from communicating:

S6 did not know what to say. She looked at S4 and said nothing. (T2, Journal 1)

It was possible to notice how S6 started to play a more active role. She helped her partners recall ideas and organize their work. When they looked for options given by the corpus, S6 helped in choosing which language form was more suitable for the manuscript. Her partners listened to her and tried to implement her recommendations when it was appropriate. Later, S6 demonstrated how much confidence she had gained, as she was willing to provide explanations, regardless of the language mistakes she would have made. Besides, her peers were willing to restate what she had mentioned in a judgment-free way whenever it was necessary, so she was confident enough to continue seeking for approval or support by looking at her partners, especially S4. She tended to speak as if she were formulating a question and seemed more comfortable when they agreed with her:

S6 gave some explanations. She tried several times to explain what was written and while doing so, she looked at S4 looking for support to express her ideas. (T2, Journal 5)

In short, there were two students who gradually became active editors of their manuscripts by working collaboratively and having a better command of the interface. It seems to be that the supportive and respectful environment inside their teams and their interest in the corpus interface empowered them to be active and confident members and to be able to take decisions in the editing process.

The mediators. The “mediators” were in charge of both interpreting the ideas provided by their partners and teacher and reporting the advances in the edition. They were constantly engaged in the processes of editing and using the corpus. In GA, S2 was able to answer all questions posed by the teacher and provided information when her partners did not participate actively in the discussions:

S2 seemed to be more confident than S1 as she participated more…she seemed to be a mediator between S1, who knew about the functions and options given by the interface, and S3, who did not want to spent time using the corpus and was not completely willing to participate in the tutoring sessions. (T1, Journal 2)

In GB, S5 was constantly in charge of explaining their ideas and the advances of their text. She was the most skillful one when using the interface:

S5 was able to answer the questions I posed. She seemed to understand what I was explaining by moving her head. (T2, Journal 3)

Finally, S9 constantly attended the sessions with questions and inquiries about the edition and the interface; however, he did not make any changes, he just informed S8 about the feedback provided. His lack of confidence was evident:

S9 arrived with a list of questions but he didn’t implement any change in the document. He says S8 is in charge of doing the corrections as he is the one with a higher level of English. (T3, Journal 3)

As evidenced above, the mediators were a group of members who participated actively in the tutoring sessions by posing questions and offering relevant information related to their work. They also helped improve communication among the participants and the teachers, and contributed to ease the mood of the tutoring sessions when the group members were reluctant to participate or were not confident enough to state their ideas. Furthermore, they seemed interested in the editing process of the manuscript and the use of the interface.

The outsiders. There were students who would not show their interest or commitment to the process in two of the groups. In GB, there was a participant (S7) who arrived after they had already consolidated their group dynamics. She did not participate voluntarily during the sessions:

S7’s reaction towards the mistakes . . . was different, she kept quiet and looked at the document and at her partners as if she were upset. She just participated when I asked her directly, but she looked confused and said she didn’t know what the text was about. (T2, Journal 4)

When T2 asked about the manuscript, she was not able to answer accurately so her partners could not agree with her. She looked worried, touched her head with her hands and looked at the others as if in search of support or help in order to answer:

S7 was quiet and took her head several times. She did not participate, except for the times I asked her directly what the text was about and she gave some ideas that the rest of the group did not accept. (T2, Journal 5)

In GC, there were two students who did not seem to be engaged at all with the editing process of their manuscript. S10 attended only two meetings. He attended one of the sessions with another partner, but he did not make any comments; in fact, he appeared to be confused about what the teacher and the other student were talking about, since he was not aware of the process and did not have any information about the assignments given and the advance in the edition of the text:

He came, but he did not participate at all. He did not show any interest. He looked at S9 and he seemed to be confused. (T3, Journal 3)

S11 is also categorized as an “outsider”. He attended the introductory session but did not establish any sort of communication with the teacher afterwards.

Overall, “outsiders” were categorized this way if they presented two of the following attitudes: first, they did not participate in the sessions despite attending all of them. In the case of S7, she did not participate because she had arrived late in the group, so she did not have as much knowledge about the project as her peers. Second, they did not attend the sessions and were not informed about the different decisions regarding the edition of the manuscript. Such was the case of S10 and S11 in GC, who were not involved in the group’s editing process.

Reflecting Upon the Group Work Process

Along the editing process, we were able to notice that each group had different perspectives when working as a team since it was not possible to identify common patterns between the analysis and descriptions we portrayed for each group in this subcategory. We divided this analysis according to each researcher and group experience.

Group A. Group A understood the dynamics of working collaboratively. In general terms, they were committed students who always attended the tutoring sessions together and were remarkably punctual to attend meetings, send the edited manuscripts, and hand in their journals with reflections about their experiences and perceptions regarding the edition process and the use of corpus.

Time was a concern for the participants since they not only had to edit, but also had to finish writing the data analysis and conclusions of their manuscript. Every session, T1 asked the participants about how they managed to correct the manuscript and use the corpus to do it. Their answers were consistent as they stated that all of them managed to meet to correct the mistakes. T1 had asked to explore the corpus interface in order to check how it could be helpful to edit their manuscript:

Sometimes it was difficult for us to meet during the week, so…we met on the weekend to work together on the manuscript. (S2, Interview 2)

Thus, students seemed to allocate time to work as a group despite the amount of work they had due to the project, so what could have been used as an excuse not to work collaboratively helped them to be good time managers and work partners.

All of the participants were able to answer questions about the editing process when they were asked individually and as a group. Despite the different identities that emerged in the tutoring sessions (the mediator, the empowered, and the overconfident one), they worked cooperatively to improve their text since all of them knew what they had changed, the reasons why and the examples found on the corpus interface that helped them to correct their manuscript. Sometimes, they would share what and how they edited voluntarily, and sometimes T1 would ask the students that had not participated to check whether they actually knew about the editing process or not; in either case, S1, S2, and S3’s answers demonstrated they were equally involved in a true collaborative environment:

So far, students have been equally engaged in the editing process. I’ve asked them about the use of corpus and the samples and they’ve agreed on the reasons why they had chosen certain corrections instead of others. Today, S1 and S2 managed to answer the questions about synonyms and collocations on the COCA interface, S3 was just nodding so I asked S3 specific questions about the collocations and synonyms they had chosen and S3 could successfully respond providing accurate arguments. (T1, Journal 4)

Group A also demonstrated they liked working together when they had to fill a document related to the use of the corpus. This process seemed time-consuming and participants expressed they were concerned about their lack of time; so T1 tested S1, S2, and S3’s attitudes towards group work by suggesting they split the corrections and then submit the paper. Nevertheless, students affirmed that they preferred to work together:

I told them to divide evenly the corrections they had to include in the chart and then e-mail it to me, but all of them refused to do so. S1 and S2 said they always worked together for editing the text and for using corpus. S3 added that it was much better to meet face-to-face as a group and discuss the corrections before any submission. (T1, Journal 4)

T1’s journals and interview revealed Group A had a successful collaborative work experience. All of the students were involved in the editing process, so they could submit the manuscript and the charts on time; also, they were familiar with the use of corpus and the corrections and they agreed on what was clear or challenging along the semester. Although every participant portrayed a different identity during the tutoring sessions, their engagement displayed in the submissions and their responses during face-to-face meetings unveiled they liked group work and could work collaboratively in an effective way.

Group B. Although at the beginning it was difficult for GB to differentiate collaborative from cooperative work, due to the tendency to divide the edition of the manuscript among the participants and join all the sections at the end, they were able later to notice the importance of working together in order to create a better quality manuscript, which could be edited more easily. They eventually decided to discuss the corrections and ideas they were going to register in their document before making them, no matter if they were meeting during the process or if they were working from different places:

At the beginning we divided the work and it made the final result very difficult, it made the text not easy to understand. Then we implemented some changes, so when we did not write as a group, we previously discussed about what to write. Therefore, although we wrote from our houses, we would have the same focus. Thereupon, after the change of methodology, the experience was very positive. (S4, Interview 2)

In order to work collaboratively, they decided to identify the skills each one had according to the different duties they had to face along the editing process. Thus, they took responsibility for some tasks, such as correcting grammar and vocabulary, revising and editing, including more ideas, using APA style, and so on. They noticed that by assuming a given task according to their abilities, they were able to complement each other and work more efficiently, which contributed to the editing process of the manuscript:

Some time here we have noticed what skill each integrant has, and so we have worked more efficiently, and I think we have been able to move forward more quickly and get better results. (S4, Interview 2)

Additionally, working collaboratively helped them gain self-confidence. The supportive and respectful environment allowed them to feel they were valuable and able to cope with the demands of the manuscript, which helped them overcome their lack of motivation and confidence. Dialogue was an important strategy to share and learn from one another; they appreciated respect towards their ideas no matter if they were enriching or in need of some correction:

I could notice how important it was for S6 and S7 to receive support from S4. Whenever they wanted to participate, they turned around and looked at S4 trying to see if he agreed with them. Whenever S4 accepted their comments, he mentioned, “as my partner just said,” and S6 and S7 looked proud of themselves. Then they tried to speak again. I think they feel more confident nowadays. (T2, Journal 4)

In short, GB realized the importance of working collaboratively since they noticed how it contributed to their goal. First, it helped them make their work more efficiently. Second, it allowed them to be aware of their skills and take responsibilities according to them. Finally, partnership and respect seemed to empower some members, who at the beginning did not show much confidence, to see how valuable they were for the group.

Group C. Group C presented very different dynamics. Despite having been informed about the collaborative work methodology for the editing process of the manuscript and its characteristics, they were unable to work this way. The main reason was their different working schedules, which did not allow them to find a proper time to meet and discuss the process as a unit:

It’s really hard to meet with the whole group because of schedule and other excuses. S9 says he is coming to the tutoring sessions representing his classmates. I think he is the only one that seems interested at all. (T3, Journal 2)

Since the students did not have time to meet all at once, the two that could meet on a regular basis assigned themselves responsibilities with the edition of their report: one was in charge of the mechanics corrections, and the other one attended the tutoring sessions with questions about the editing process and reported back to the “corrector”. The other two however, did not have clear responsibilities during the process. This did not really help raise their interest and engagement as members of a group:

I think some of my classmates don’t work as hard as me and S8, and S8 is in charge of the correction because he knows more. The others never have time. (S9, Interview 3)

Since collaborative work is based on the active participation of all the students of the group, and this enables the negotiation of ideas, clear roles, and strategies in the construction of knowledge (César & Santos, 2006), we could see that this group did not really work collaboratively during the process, an observation that had two serious consequences in the group dynamics and in the overall outcome of the process itself: students’ lack of information about the process, and students’ tasks (or lack of them) as participants of the group.

First, not all students were properly informed about how to implement the corpus as an editing tool. This was made evident when S10 came to a session with S9 and was unaware of what S9 and T3 were talking about, especially in relation to the functions of the interface:

Today I helped them and explained S9 and S10 how to fill in the chart with the corpus corrections (S10 had no idea of what I was talking about! He just looked at S9 in awe). (T3, Journal 3)

Second, since only two participants were assigned tasks inside the group, they had to divide their work. These assignments emerged from S8’s apparent higher English proficiency level, and S9’s lack of confidence in his own skills:

Apparently some of the participants are not working as hard as the others, and the corrections of the final version has fallen on one person alone (S8) and S9 does his best but it is not enough. I also asked S9 about S8 being the only one that makes changes in the document, and he says that since S8 is the one with the higher level, he is the one who usually corrects the text. (T3, Journal 4)

Hence, some GC members’ lack of time and commitment affected the editing process they carried out negatively. They were deprived from working collaboratively and as a unit, which was expected from them because the manuscript belonged to all four members of the group. This is evidenced since the corrections were made by only one person despite the need for the text to have been written by all of them.

All in all, the patterns of group work varied substantially among the different cases, which is why students’ behaviors and reactions and also the teachers’ observations and insights were so different. One aspect that could affect collaborative work is students’ investment and interest since working together implies having the availability and time to meet other participants. Additionally, the relation participants of a group have among themselves and the voices and identities they have as part of the group are also very important.

Conclusions

We identified four different language learner identities that emerged in EFL pre-service teachers when working collaboratively: the overconfident learners, the empowered learners, the mediators, and the outsiders. Additionally, we were able to analyze insights about group dynamics and the students’ and the teachers’ views about collaborative work.

At the beginning of the editing process, the overconfident learners did not think the corpus interface was useful enough since they thought they had the knowledge to edit their manuscripts without using a corpus. However, along the process they changed their attitude and accepted the corpus as having been a useful tool.

The empowered learners were not confident at the beginning. However, their hard work on the corpus and group support empowered them to be more confident and to participate actively in the tutoring sessions and the editing process. They made the most of the corpus interface and the group dynamics, so they gave themselves the opportunity to learn from the tool and enriched both the group work and the editing process.

The mediators enriched the editing process and the experience inside the tutoring sessions. They enabled communication among the participants and the teachers and eased the mood when students did not want to participate or did not understand the teachers’ instructions.

Finally, the outsiders were learners who did not participate actively in the editing process because of their lack of information or because they did not attend all the tutoring sessions, so they did not have as much knowledge about the project in comparison to their peers. They may not have seized the opportunity to learn from the process as their fellow partners did, so they affected the group dynamics.

In regard to the students’ and teachers’ insights about the experience working collaboratively when editing academic texts, some of the students tended to blend the concepts of cooperation and collaboration as they accepted dividing topics, working individually, and joining parts of the text which evidenced that not all the participants understood the concept of working collaboratively in the same way.

Groups that actually worked collaboratively reported that they felt successful with the editing process and experienced a more inclusive work environment and group dynamics. Not working collaboratively made it harder for the students to edit their manuscript and to have a good command of the corpus interface. The lack of collaborative writing deprived some participants from learning from each other. Some of them even quit or avoided their responsibility at the moment of editing their manuscripts.

It was evidenced that working collaboratively requires time to meet and work as a team, identifying peers’ abilities, agreeing on what to write and having a common focus, interest and determination to get involved. The lack of these aspects might affect the group dynamics and the effectiveness of the students’ participation. Furthermore, values such as camaraderie, respect, and support ensure collaborative work and let participants learn from one another.

References

Biber, D., Conrad, S., & Reppen, R. (1998). Corpus linguistics: Investigating language structure and use (1st ed.). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511804489.

Burns, A. (1999). Collaborative action research for English language teachers. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

César, M., & Santos, N. (2006). From exclusion to inclusion: Collaborative work contributions to more inclusive learning settings. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 21(3), 333-346. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF03173420.

Daiute, C. (1986). Physical and cognitive factors in revising: Insights from studies with computers. Research in the Teaching of English, 20(2), 141-159.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Galegher, J., & Kraut, R. E. (1994). Computer-mediated communication for intellectual teamwork: An experiment in group writing. Information Systems Research, 5(2), 110-138. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/isre.5.2.110.

Halliday,M. A.K. (1985). Spoken and written language (2nd ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Hirvela, A. (1999). Collaborative writing instruction and communities of readers and writers. TESOL Journal, 8(2), 7-12.

Lewin, B. A., Fine, J., & Young, L. (2001). Expository discourse: A genre-based approach to social research text. New York, NY: Continuum.

Norton, B. (1997). Language, identity, and the ownership of English. TESOL Quarterly, 31(3), 409-429. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3587831.

Oshima, A., & Hogue, A. (1999). Writing academic English. New York, NY: Longman.

Oxford, R. L. (1997). Cooperative learning, collaborative learning, and interaction: Three communicative strands in the language classroom. The Modern Language Journal, 81(4), 443-456. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1997.tb05510.x.

Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Saldaña, J. (2011). Fundamentals of qualitative research: Understanding qualitative research. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Storch, N. (2005). Collaborative writing: Product, process, and students’ reflections. Journal of Second Language Writing, 14(3), 153-173. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2005.05.002.

Thacher, D. (2006). The normative case study. American Journal of Sociology, 111(6), 1631-1676. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/499913.

Toohey, K. (1998). “Breaking them up, taking them away”: ESL students in grade 1. TESOL Quarterly, 32(1), 61-84. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3587902.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The development of higher psychological process. London, UK: Harvard University Press.

Weedon, C. (1987). Feminist practice and poststructuralist theory. London, UK: Blackwell.

Wolsey, T. D., Lapp, D., & Fisher, D. (2012). Students’ and teachers’ perceptions: An inquiry into academic writing. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 55(8), 714-724. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/JAAL.00086.

Yate González, Y. Y., Saenz, L. F., Bermeo, J. A., & Castañeda Chaves, A. F. (2013). The role of collaborative work in the development of elementary students’ writing skills. PROFILE Issues in Teachers Professional Development, 15(1), 11-25.

Zúñiga, G., & Macías, D. F. (2006). Refining students’ academic writing skills in an undergraduate foreign language teaching program. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 11(17), 311-336.

The Authors

Lorena Caviedes is a teacher at Universidad El Bosque, Colombia. She holds an MA in applied linguistics to the TEFL from Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas, Colombia. Her research interests include discourses, identities, and collaborative work inside EFL classrooms.

Angélica Meza is a teacher at Universidad El Bosque, Colombia. She holds an MA in education from Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Colombia. Her current research interests include ELT methodology, curriculum design, and collaborative work in the EFL classroom.

Ingrid Rodríguez is a teacher at Universidad El Bosque, Colombia. She holds an MA in applied linguistics from Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas, Colombia. Her research interests include collaborative work and teachers’ and students’ beliefs and reflections.