http://dx.doi.org/10.19183/how.24.1.311

Extensive Listening in a Colombian University: Process, Product, and Perceptions

Escucha extensiva en una universidad colombiana: proceso, producto y percepciones

Carlos A. Mayoraa

aUniversidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia. E-mail: carlos.mayora@correounivalle.edu.co.

Received: May 29, 2016. Accepted: November 3, 2016.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Mayora, C. A. (2017). Extensive listening in a Colombian university: Process, product, and perceptions.

HOW, 24(1), 101-121. http://dx.doi.org/10.19183/how.24.1.311.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. License Deed can be consulted at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

The current paper reports an experience implementing a small-scale narrow listening scheme (one of the varieties of extensive listening) with intermediate learners of English as a foreign language in a Colombian university. The paper presents (a) how the scheme was designed and implemented, including materials and procedures (the process); (b) how the students performed in the different activities with an emphasis on time spent watching/listening and their perceptions of video difficulty and self-rated comprehension (the product); and (c) how the students felt and viewed the experience (perception). Product and perceptions showed that the pedagogical implementation was positive which leads to a discussion of a number of implications for this context and similar ones.

Key words: Authentic materials, comprehension, extensive listening, narrow listening, news.

El presente artículo reporta una experiencia en la cual se implementó un modelo de escucha focalizada (una de las modalidades de la escucha extensiva) de pequeña escala con alumnos de nivel intermedio de inglés como lengua extranjera en una universidad de Colombia. El artículo presenta (a) el diseño y la implementación del modelo, incluyendo materiales y procedimientos (el proceso); (b) el desempeño de los alumnos en las diferentes actividades con énfasis en tiempo dedicado a la escucha, y la valoración de los estudiantes respecto a la dificultad de los materiales y su propia comprensión (el producto); y (c) cómo los estudiantes se sintieron y valoraron la experiencia (percepción). La combinación de producto y percepciones muestra que la implementación pedagógica fue positiva y conducen a una serie de implicaciones pertinentes para este y otros contextos educativos.

Palabras clave: comprensión, escucha extensiva, escucha focalizada, materiales auténticos, noticias.

Introduction

Intensive listening has been the dominant approach to the teaching of foreign language listening. Broadly described, in intensive listening the teacher brings an oral text (audio-only or video) to the class and guides the students through a three-phase classroom procedure including activities before, while, and after listening. The audio is played by the teacher a number of times (usually between two and three) and the activities of each phase are reviewed either as a whole class or in small groups. In the last decade, different language teaching experts have built a case in favour of extensive listening (Krashen, 1996; Renandya, 2011; Rodrigo, 2004), an alternative approach that draws largely on the theoretical bases of and practical experiences from extensive reading. In fact, Lynch (2009) has defined extensive listening as “the oral equivalent of extensive reading” (p. 153). Thus, extensive listening (EL henceforth) can be defined and described by adapting five broad principles that define extensive reading:

There are several advantages to implementing EL in contexts where English as a foreign language (EFL) is taught. First of all, it can increase the amount of exposure to spoken English since for many EFL learners “their teacher is the only consistent source and the English class the only opportunity of exposure to the language” (Cárdenas & Chaves, 2013, p. 341). Secondly, EL reduces the feelings of anxiety and frustration learners experience in intensive listening classes since they can control the pace (number of repetitions) of delivery of the oral text and select the topic of the listening material (Renandya & Farrell, 2011). Thirdly, it allows learners to actually listen more and to truly focus on content (Renandya, 2011; Rodrigo, 2004). Finally, it opens a space for listening to more authentic materials as opposed to artificially controlled audios from commercially produced textbook series. These and other benefits have been confirmed by different empirical studies (Dupuy, 1999; Ewert & Mahan, 2012; Yeh, 2013).

Different listening activities that involve learners listening for meaning and enjoyment, independently from the class, can be classified as EL. Such activities include, among others, narrow listening, reading-and-listening, and other modalities designed for self-access centres. Particularly important for the current paper is narrow listening which involves learners listening to many oral texts that are connected or “narrowed” by one overarching feature, be it topic, genre, or author (Krashen, 1996; Rodrigo, 2004). Examples of these would be EFL learners listening to many audio books from the same author or to several recordings of native-speakers discussing the same topic. It has been proposed that by listening to texts that are narrowed down thematically or discursively, students’ chances of re-encountering the same vocabulary and/or discursive features increase, thereby increasing learners’ familiarity with the content, vocabulary, and other textual and oral characteristics concurrently (Rodrigo, 2004).

Among the recommended materials that can be used for EL and its different varieties are the following: graded-readers audio books (Ewert & Mahan, 2012; Lynch, 2009), teacher-produced recordings of conversations with native-speakers (Krashen, 1996), teacher produced recordings of native-speakers in monologues or interviews (Dupuy, 1999; Rodrigo, 2004, 2008); online audio/video libraries for EFL learners such as English Listening Lesson Library Online or ELLLO, Dave’s ESL Café, or Voice of America (Ewert & Mahan, 2012; Renandya & Farrell, 2011); Podcasts (Renandya & Farrell, 2011; Yeh, 2013); and even TED talks (Takaesu, 2013).

In spite of the growing number of reports of experiences implementing EL in different contexts and with different materials, the approach is still infrequent in Latin America. Considering the potential advantages of EL, it seems evident that the approach could be beneficial for the teaching of EFL in such context. One particular example is Colombia, a country in which the national government has adopted a bilingualism policy that aims at having all high school graduates reach a B1 level in English by the end of their studies and all college graduates reach a B2 level. However, this policy has been far from successful (Cárdenas, Chaves, & Hernández, 2015; Education First, 2015; González, 2015) because of, among other reasons, learners’ limited exposure to the language and the prevalence of traditional methods in schools.

The current paper reports on an experience implementing a small-scale narrow listening scheme with intermediate learners of EFL in a Colombian university. The paper presents (a) the design and implementation of EL including materials and procedures (the process); (b) the performance of the learners in the different EL activities (the product); and (c) the perspectives and comments from the students regarding EL (perception). As such, this is not a primary research report. Yet, it is expected that the article will provide general guidelines on how to implement EL in similar contexts and to contribute to building up pedagogical and practical knowledge in the use of EL in Latin America.

Context

The EL scheme heretofore described was implemented in an “English V” class of students of the Bachelor of Education degree programme in foreign languages at Universidad del Valle in Cali, Colombia. Students in the B.Ed. program are simultaneously trained to teach both English and French. The program is made up of four components: foreign languages (English and French), linguistics and first language (Spanish), research and pedagogy, and language teaching. Within the EFL component, the first four courses, labelled as integrated skills in English I to IV, are four-skill courses that aim at developing the students’ language proficiency. The fifth course, labelled as Oral Text Typologies in English V, aims at developing advanced listening and speaking skills in English. The sixth and seventh courses concentrate on academic reading and writing, respectively, while the eighth and ninth courses focus on literature from English-speaking cultures. Each course is a semester long (16 weeks) and provides six weekly hours of instruction.

Twenty-six students were enrolled in the aforementioned English V class (18 females, eight males) and had taken 312 hours of instruction in English in their two previous years of studies in the B.Ed. program. Students’ ages ranged from 19 to 35 with a mean of 21. By the mid-term period, two students dropped the course, rendering 24 participants.

As stated before, the English V class aims at developing learners’ listening and speaking skills. The course is structured around different oral text genres (news reports, speeches, documentaries, academic/professional oral presentations, advertisements, TV shows, movies, etc.). Typically, the course involves a lot of intensive listening and students doing oral presentations emulating the characteristics of the genres and texts previously worked in class. The course was designed and implemented according to these general guidelines but included the EL component.

Extensive Listening Implementation

Process

Among the different EL modalities, narrow listening was chosen. An accompanying class blog was created for course management purposes (available at http://univalleenglishv.blogspot.com/) and an overview of EL and the specific instructions for the activities were posted there (visit http://univalleenglishv.blogspot.com/p/blog-page_27.html). Students were instructed to look for videos weekly on their own time, watch them, and complete an online EL worksheet for each selected video. The only requirements were as follows: (a) videos should be news reports in English, (b) students should complete a minimum of two worksheets each week during a period of 11 weeks for a total of 22 worksheets, and (c) videos should be at least one-minute long.

A much-debated topic in extensive reading is the suitability of authentic materials as source reading texts versus the suitability of simplified materials especially at intermediate and advance levels. For some authors, simplified materials offer learners both comprehensible input (Krashen, 1991) and opportunities for them to be exposed to specific target vocabulary and structure that aid acquisition (Hill, 2008). On the other hand, simplified materials are often criticized for the artificiality and unnaturalness of the language they contain and expose learners to (Berardo, 2006). A similar debate arises in EL since comprehensibility of the oral texts is considered a crucial feature of the approach. In the current experience, authentic videos were chosen as input sources because of their motivational potential and availability online (Yeh, 2013). In order to compensate for the inherent difficulty of authentic videos, students were given the freedom to select what videos to watch. It was believed that the freedom to self-select materials and the increasing familiarity resulting from repeated exposure to the same genre would aid comprehensibility while offering learners the chance to be exposed to natural and realistic spoken English.

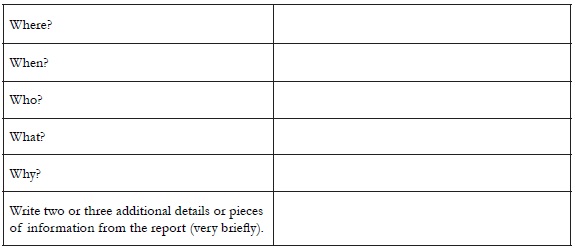

The EL worksheet was designed based on Pino-Silva’s (1992, 2009) extensive reading worksheet and some suggestions for designing generic worksheets for self-access listening centres recommended by Lynch (2009). The worksheet consisted of three parts. The first part collected general information about the video such as title, URL, category (sports, breaking news, science and technology, world news, entertainment, or other), length, and dominant rhetoric function (description/definition, comparison and contrast, process, chronological order, argument, or other). The overall purpose of this part was collecting information on the kind of videos students chose to watch.

The second part required students to answer very general comprehension questions that could be relevant to any piece of news (who, what, where, when, etc.). The purpose was not to “test” students’ comprehension, but to provide them a focus for attention while watching and to create a sense that they were doing some comprehension task and not just “watching”.

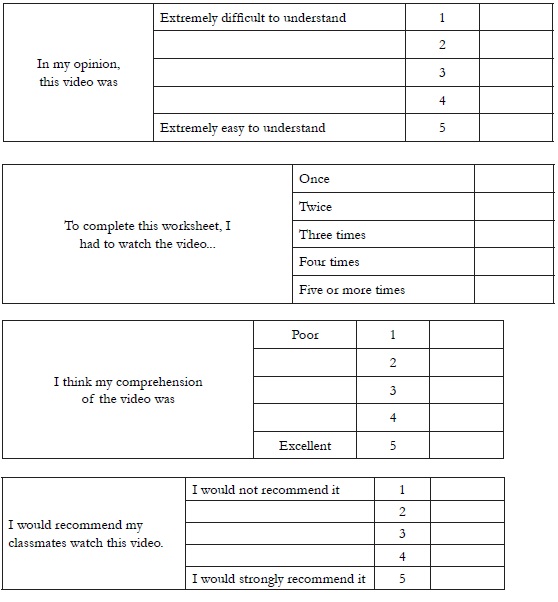

Finally, the last section collected information on the students’ experience interacting with the video including their own rating of difficulty of the video and their perceived comprehension. Students were also requested to inform how strongly (if at all) they would recommend the selected videos for other classmates to watch. The purpose of this section was to collect information on how students felt about their performance while doing the activity and to help them reflect on the viewing experience. The complete EL worksheet is presented in Appendix 1.

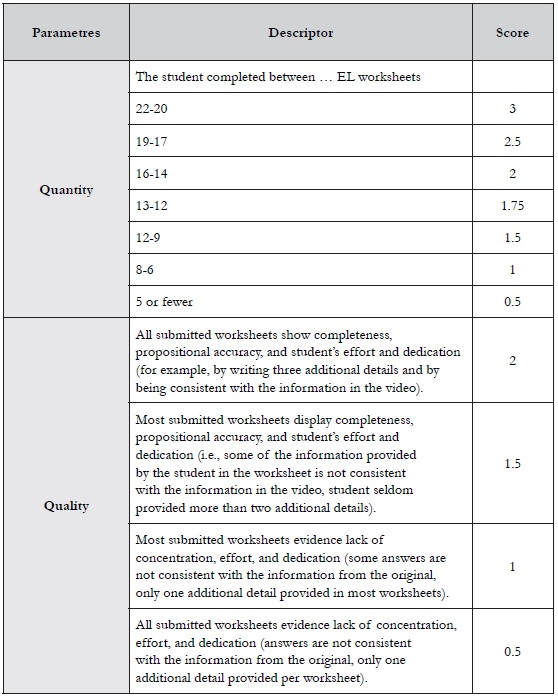

In many of the previously reported EL implementations, no credit or grades were assigned for the activities. In this particular case, the narrow listening activity was conceived as an integral part of the course and not as an additional out-of-class activity, so credit was given for completing the weekly worksheets. Grading criteria were designed in line with the five broad principles that define EL (listed above), placing emphasis on quantity of videos watched and completeness of the submitted worksheets. Students’ responses were not corrected or graded and only the questions in the second sections were reviewed for propositional consistency with the original video in order to avoid cheating and to determine if the video had actually been watched. Linguistic accuracy (spelling, vocabulary, or grammar) was not taken into account. The scoring rubric for the EL activity is presented in Appendix 2.

Another course activity assigned to the students was keeping an audio journal using podcasts. Their audio journal should have had at least three entries during the term (or three podcasts) and a protocol of topics and questions were suggested which they could use as guidelines for what they had to record (visit http://univalleenglishv.blogspot.com.co/p/audio-journal-topics.html). On the whole, the suggested topics invited students to reflect on their listening and speaking skills and their experiences along the course. Although none of the suggested protocols directly addressed EL, some of the students decided to comment on the activity and their experience a motu proprio which provided data on students’ perceptions.

Products

In this section, performance of the students in the EL activities is reported, namely, the amount of videos watched, time spent watching them, and the students’ ratings of text difficulty and comprehensibility of the videos. A complete report of all students’ answers is beyond the length and scope of the present paper.

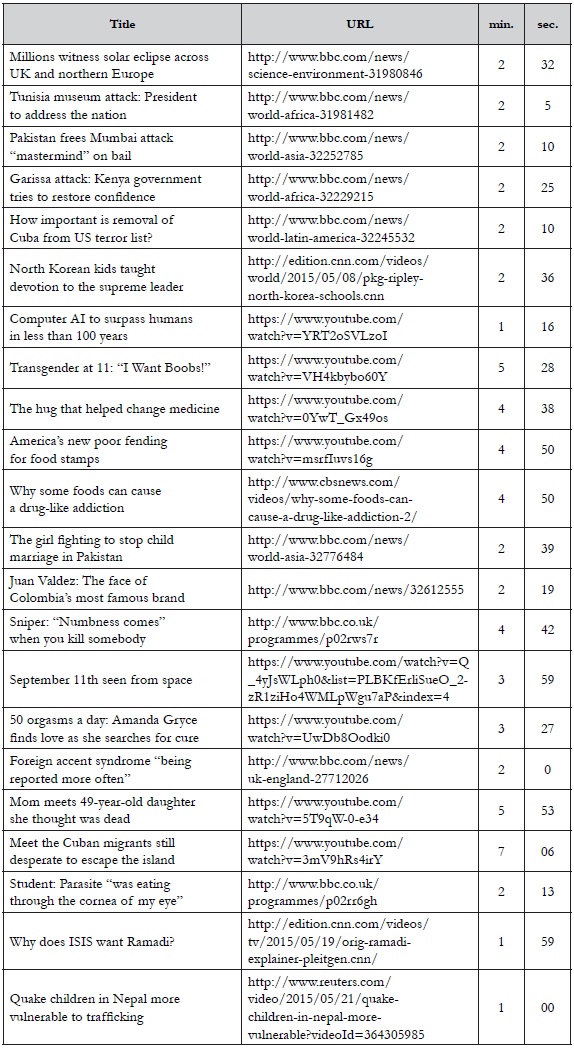

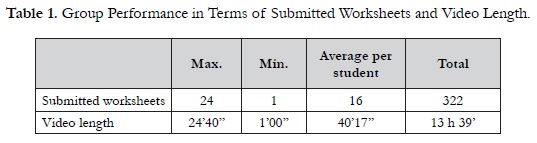

Out of the 24 students in the class, 20 completed the activity while the remaining four did not complete any worksheets. These 20 students completed 322 worksheets and watched 306 videos (some videos were watched by more than two students). Three students completed 24 worksheets, doing more than two worksheets per week. Five students completed between 20 and 23 worksheets, eight students completed between 10 and 19, and four students completed less than 10 worksheets. Some sample titles of the videos selected by students are available in Appendix 3.

Video length ranged between one minute (shortest video) and 24 minutes and 40 seconds (longest). In total, these 20 students watched 14 hours and 45 minutes of videos, for an average of 42 minutes and 11 seconds of additional exposure to spoken authentic English outside class. However, in order to arrive at a proper estimation of time spent watching, it was also necessary to consider the number of times the students reportedly watched each video. Of the statement, “To complete this worksheet, I had to watch the video...” followed by options that represented the numbers of viewings from one (once) to five (five times or more), twice (n = 119) and three times (n =75) were the most frequently selected answers. If averaged, the number of viewings per video equals 2.4 which doubles the amount of time and exposure each student had to roughly 96 minutes and 42 seconds. This information is summarized in Table 1.

When looking at performance individually, the diversity of the work done by the students along the semester became evident. This information is summarized in Table 2. By freely choosing videos, most students were exposed to over 40 additional minutes of English. Most students generally watched the videos more than once, thus increasing the time of exposure. The student labelled as “5” in Table 2 selected longer videos to manage completion of 139 minutes (over two hours). On the other extreme, many students did not complete the minimum of required worksheets thereby getting very little exposure. The most notable cases in this trend were students labelled as “3, 8, 18, and 19”.

Since students worked on self-selected videos from the Internet in this EL experience, it was interesting for the current study to explore students’ perceptions of difficulty and their own assessment of comprehension of these materials. This information is reported in Figures 1 and 2.

Of the statement, “in my opinion, this video was ... to understand”, which was followed by options that represented levels of difficulty from 1 (extremely difficult) to 5 (extremely easy), the options extremely easy and easy were the most frequently selected. As can be seen in Figure 1, from the 322 submitted worksheets, 227 videos were rated as easy or extremely easy to understand by the students, while 38 were rated as difficult to extremely difficult. On average, overall perception of video text difficulty was rated 3.9 on the 1 to 5 scale.

Of the statement, “I think my comprehension of the video was...”, which was followed by options that represented quality of resulting comprehension from 5 (excellent) to 1 (poor), options 5 and 4, the best levels of comprehension, were the most frequently selected, with 247 responses from the total, 322. On the other hand, options 1 and 2, representing poor levels of comprehension, were selected 25 times. On average, overall self-rating of comprehension was rated 4.1 over the 1 to 5 scale.

In short, it can be seen that students reported feeling comfortable with the videos they worked on, even when these were authentic videos taken from the Internet and from genuine online news sources. Students’ answers suggested that they felt the videos were not too difficult and that their comprehension was satisfactory. Different interpretations of these data might be put forward. It can be said that students are being affected by social desirability, that is, giving answers that reflect the best socially acceptable response (see Dörnyei & Taguchi, 2010). Considering that this part of the worksheet would not be graded or taken into account for such purposes, this explanation could be disregarded. It could also be argued that, since students were free to select what to watch and set their own pace for watching, it is only natural to see that they stayed within a comfort zone, choosing simpler videos and avoiding challenging ones. A look at some of the videos might disregard this explanation as well since it is evident that many of these videos were actually complex in both content and language.

An alternative explanation might be found in the concept of locus of control (Rotter, 1966). A person’s locus of control refers to “a particular personality trait which measures the extent to which a person attributes control over the outcome of environmental events to one-self” (Declerck, Boone, & De Brabander, 2006, p. 144). People who attribute such control to themselves are classified as internal; while those who attribute controls to other people, luck, or fate are usually classified as externals. This psychological construct was adapted by Norton Peirce, Swain, and Hart (1993) for communicative events in the following way:

In a communicative event . . . the locus of control is said to reside with the participant (or participants) who exercise dominant control over the rate of flow of information. . . . If a communicative event takes place in “real time”, i.e. when the language learner has little time to process information and cannot reflect on what is being communicated, the locus of control does not reside with the language learner. When the language learner can control the rate of flow of information in a communicative event and reflect on what is being communicated, the locus of control does reside with the language learner. (pp. 36-37)

According to the cited authors, this explains why reading and writing skills are often stronger in second or foreign language learners before they fully develop listening and speaking skills. Learners can control the pace at which they read, they can plan and edit their writing and, therefore, they feel they control the flow of information, whereas in listening, it is the speaker who usually controls the flow of information. Naturally, through meaning negotiation and communication strategies, learners can share the locus of control in a communicative event (Norton Peirce et al., 1993). However, in intensive listening, the locus of control resides in the teacher who decides how many times the audio/video will be played and at what particular points pauses will be made. In EL, the locus of control resides within learners, for it is they who choose the video, watch it at their own pace, play it back according to their own needs, and who may decide to look for another video if they did not enjoy or understand their first choice. Furthermore, Norton Peirce et al. (1993) also suggested that locus of control in a communicative event might impact the perceptions of difficulty students have regarding a text or task in the classroom. The lesser the control they have on the task, the more difficult it will seem to them. Thus, it is plausible to believe that as EL places the locus of control on students, this favours their perception of difficulty and improves their own rating of comprehension. In turn, this might have a positive effect on their motivation, since tasks that are deemed too challenging for students often result demotivating (Dörnyei, 2010).

Needless to say, these interpretations are only hypothetical and need to be confirmed through further studies and more rigorous research design. For the purposes of the current paper, the products of the students show that these authentic videos were adequate for the activity and did not seem to pose an overwhelming challenge to the students.

Perceptions

In the audio journal activity, students produced 75 podcasts in which they reflected on their learning, the course, the materials and activities, their perceptions of achievement, and the difficulties they experienced along the course. From these, comments and reflections about EL were present in 12 podcasts. Since none of the topics explicitly required students to comment on this activity exclusively, the scarcity of comments about EL is understandable.

The recordings were listened to, transcribed, and then analysed to determine common patterns in the comments and establish students’ overall perception of the extensive listening activity. The comments were grouped according to recurrent topics and ideas expressed. Overall, the students who commented on EL considered that doing this activity was positive, that it helped them improve their listening skills, develop familiarity with a variety of accents in English, learn new words and expressions that are not frequent in instructional materials, and develop a sense of confidence when listening to “real” English. They also valued the activity because, being news reports the main source of input, it allowed them to be better informed about current events and what “is happening in the world right now” (Student 6, Audio journal 2).

Moreover, their comments also valued the sense of “freedom” (Student 5, Audio journal 2) the activity creates by allowing them to choose the videos to watch rather than having them “imposed by the teacher.” This is an example comment from this perspective: “the extensive listening was a very productive activity that helped me to understand different accents and learning new vocabulary”1 (Student 14, Audio journal 3). Another student highlighted the sense of independence the activity provided:

Sometimes in class I have to listen again a video or audio I understood because other classmates didn’t understand. And sometimes I would like to listen again but the majority says they understood so the video is not played again. I like that I could listen just once or I could listen as much as I wanted and not to depend on the others classmates. (Student 5, Audio journal 2)

In spite of the positive comments, the fact that not all students completed the activity stands out as a concern. The reasons for this emerged in three of the podcasts and in out-of-class conversation with the four students who did not complete the EL activity. One of the students made a somewhat negative comment about EL saying that he “didn’t think it was interesting” and that he “was not into it” (Student 21, Audio journal 2).

Limited access to the Internet and lack of time were the most often cited reasons for not having done or completed the activity as shown in these comments:

Next year I am going into an international exchange program and I...I have been too busy with the paperwork to get the visa and stuff...so didn’t do it because I don’t have time. (Student 23, Audio journal 3)

My computer broke and I had to borrow a friends’ and it was very uncomfortable. (Informal conversation with one of the students)

In brief, overall perception seemed to have been positive with very few negative comments. On the other hand, time management on the part of some students and technical problems were reported as the limitations to the EL scheme.

Implications and Concluding Remarks

The EL activity provided more exposure time to authentic English for the students in this class, approximately an average of one hour and a half more. Yet, this result is far from being satisfactory if one considers that these students are at college level and pursuing a degree in foreign language teaching. Future implementations with this type of students should be for instructors to consider requesting students to watch longer videos (at least two minutes in length) and complete more worksheets weekly over a longer period of time. Notwithstanding, the time and quantity limit established in the current study might be very appropriate for students in other contexts for whom exposure is far more limited and whose English learning goals are different such as EFL learners at public middle and high school, or for ESP programs in different majors.

Another conclusion that might be drawn is that the choice of news reports as the selected source of input seems to be appropriate. In their audio journals, students reported finding the activity satisfactory and highlighted the learning of content as a positive asset of the activity. Some students, on the contrary, occasionally selected non-news videos for the activity. This was not considered negative since students were still listening to English and, in some cases, to segments that were longer than the average news report. In future implementations of this activity, instructors might consider the possibility of expanding the possible options for videos or being more flexible on what students can choose.

Students’ reactions to the use of authentic videos from the Internet are worth commenting on. One of the arguments against the use of authentic materials is that they often result as being incomprehensible for the students and therefore too challenging and often demotivating. In the present study, authentic materials were used and the results from perceived difficulty, self-rated comprehension, and the overall students’ perceptions of the activity suggest that in this particular context and with these particular students, authenticity did not sacrifice comprehensibility. This might be the result of the “narrow” approach implemented or simply a result of the students’ level and previous training. An alternative explanation is that by allowing students to choose freely, they can select those from the pool of large options of authentic materials that are more suitable, that is, within their current linguistic and comprehension level. This might be explained from the stance of self-regulated behaviour—students’ being able to self-assess and monitor their linguistic and cognitive resources and use them effectively as suggested by Oxford (2011)—or from the stance of locus of control in a communicative event—the greater the extent learners feel in control of the flow of information in an interaction, the easier they rate the task as suggested by Norton Peirce et al. (1993). In intensive listening, where students rarely choose what to listen to, authentic materials might lead to the often reported frustration and demotivation. In EL, students are free to select a video and then select another according to their level and interests. Moreover, the possibility of listening at their own pace and as many times as they need to might help learners find these authentic materials more comprehensible.

Although students watched fewer videos than expected, the overall results of the activity were positive. Some students took advantage of the activity to expose themselves to more English while others did not. This first experience has provided interesting insights to improve the design for future implementations.

1Students’ comments were transcribed verbatim. No corrections or editions were added.

References

Berardo, S. A. (2006). The use of authentic materials in the teaching of reading. The Reading Matrix, 6(2), 60-69. Retrieved from http://www.readingmatrix.com/articles/berardo/article.pdf.

Cárdenas, R., & Chaves, O. (2013). English teaching in Cali: Teachers’ proficiency level described. Lenguaje, 41(2), 325-352.

Cárdenas, R., Chaves, O., & Hernández, F. (2015). Implementación del programa nacional de bilingüismo, Cali Colombia: perfiles de los docentes [Implementation of the National Bilingualism Program in Cali, Colombia: Teachers’ profiles described].Santiago de Cali, CO: Fondo editorial de la Universidad del Valle.

Declerck, C. H., Boone, C., & De Brabander, B. (2006). On feeling in control: A biological theory for individual differences in control perception. Brain and Cognition, 62(2), 143-176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2006.04.004.

Dörnyei, Z. (2010). Teaching and researching motivation (2nd ed.). London, UK: Routledge.

Dörnyei, Z., & Taguchi, T. (2010). Questionnaires in second language acquisition research: Construction, administration, and processing. New York, US: Routledge.

Dupuy, B. C. (1999). Narrow listening: An alternative way to develop and enhance listening comprehension in students of French as a foreign language. System, 27(3), 351-361. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(99)00030-5.

Education First. (2015). English proficiency index 2015. Retrieved from http://media2.ef.com/__/~/media/centralefcom/epi/downloads/full-reports/v5/ef-epi-2015-english.pdf.

Ewert, D., & Mahan, R. (2012). Extensive listening in a self-access learning environment. In J. M. Perren, K. M. Losey, D. O. Perren, J. Popko, A. Piippo, & L. Gallo (Eds.), Selected proceedings of the 2011 Michigan Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages Conference (pp. 24-40). Kalamazoo, US: Michigan Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages.

González, A. (2015). ¿Nos han desplazado? ¿O hemos claudicado? El debilitado papel crítico de universidades públicas y los formadores de docentes en la implementación de la política educativa lingüística del inglés en Colombia [Have we been removed? Or have we given up? The weakened critical role of public universities and teacher educators in implementing linguistic and educational policy regarding English in Colombia]. In K. A. da Silva, M. Mastrella-de-Andrade, C. A. Pereira Filho (Eds.), A formação de professores de línguas: políticas, projetos e parcerias (pp. 33-54). Campinas, BR: Pontes Editores.

Hill, D. R. (2008). Graded readers in English. ELT Journal, 62(2), 184-204. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccn006.

Krashen, S. D. (1991). The Input Hypothesis: An update. In J. E. Alatis (Ed.), Georgetown University round table on languages and linguistics 1991: Linguistics and language pedagogy (pp. 409-431). Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Krashen, S. D. (1996). The case for narrow listening. System, 24(1), 97-100. https://doi.org/10.1016/0346-251X(95)00054-N.

Lynch, T. (2009). Teaching second language listening. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Mayora, C. A., Nieves, I., & Ojeda, V. (2014). An in-house prototype for the implementation of computer-based extensive reading in a limited-resource school. The Reading Matrix, 14(2), 78-95. Retrieved from http://readingmatrix.com/files/11-g736917w.pdf.

Norton Peirce, B., Swain, M., & Hart, D. (1993). Self-assessment, French immersion, and locus of control. Applied Linguistics, 14(1), 25-42. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/14.1.25.

Oxford, R. L. (2011). Teaching and researching: Language learning strategies. London, UK: Pearson.

Pino-Silva, J. (1992). Extensive reading: No pain, no gain? English Teaching Forum, 30(2), 48-49.

Pino-Silva, J. (2009). Extensive reading through the Internet: Is it worth the while? International Journal of English Studies, 9(2), 81-96.

Renandya, W. A. (2011). Extensive listening in the second language classroom. In H. P. Widodo & A. Cirocki (Eds.), Innovation and creativity in ELT methodology (pp 28-41). New York, US: Nova Science Publisher.

Renandya, W. A., & Farrell, T. S. C. (2011). “Teacher, the tape is too fast!”: Extensive listening in ELT. ELT Journal, 65(1), 52-59. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccq015.

Rodrigo, V. (2004). Aproximación teórica y respuestas pedagógicas al desarrollo de la audición a nivel intermedio [Theoretical underpinning and pedagogical responses to the development of intermediate level listening comprehension]. Hispania, 87(2), 312-323. https://doi.org/10.2307/20140861.

Rodrigo, V. (2008). Fundamentos y evaluación de la audición extensiva y enfocada en el desarrollo de la destreza auditiva: español en Estados Unidos [Underpinnings and evaluation of extensive and narrow listening in the development of listening skills: Spanish in the USA]. In S. Pastor Cesteros & S. Roca Marín (Eds.), La evaluación en el aprendizaje y la enseñanza del español como lengua extranjera / segunda lengua (pp. 533-539). Alicante, ES: Servicio de publicaciones de la Universidad de Alicante.

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs, 80(1), 1-28. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0092976.

Takaesu, A. (2013). TED talks as an extensive listening resource for EAP students. Language Education in Asia, 4(2), 150-162. https://doi.org/10.5746/LEiA/13/V4/I2/A05/Takaesu.

Yeh, C.-C. (2013). An investigation of a podcast learning project for extensive listening. Language Education in Asia, 4(2), 135-149. https://doi.org/10.5746/LEiA/13/V4/I2/A04/Yeh.

The Author

Carlos A. Mayora holds a B.Ed. in English as a foreign language from Instituto Pedagógico de Caracas (2000) and an M.A. in applied linguistics from Universidad Simón Bolívar (Venezuela). He is currently an assistant teacher at Escuela de Ciencias del Lenguaje, Universidad del Valle, Colombia.

Appendix 1: Extensive Listening Worksheet

Watch a news report on the web and after watching it please complete the following worksheet with the required information.

Full name: _________________________________. Student ID: _________________

Class number: ________________

About the video

1. Please complete the following general information about the video.

Video title: ____________________________. URL: ____________________

2. Category (choose one or use the “other” space if necessary):

Sports

Breaking news

Science and tech

World news

Entertainment

Other: ________________

3. Which rhetoric function do you think is dominant in the text? (choose one or use the “other” space if necessary):

Description/definition

Comparison and contrast

Process

Chronological order

Argument

Other: ________________

Listening for specific information

4. Complete the following chart with information from the video. If one of the questions is not answered in the video write N/A.

Your experience

5. Now rate your experience working with the video.

Appendix 2: The Extensive Listening Scoring Rubric

Appendix 3: Sample List of Some of the Videos Selected by Students