http://dx.doi.org/10.19183/how.24.2.335

Standardized Test Results: An Opportunity for English Program Improvement

Resultados de exámenes estandarizados: una oportunidad para el mejoramiento de un programa de inglés

Maureyra Jiméneza

Caroll Rodríguezb

Lourdes Rey Pabac

aUniversidad Simón Bolívar, Barranquilla, Colombia. E-mail: mjimenez1@unisimonbolivar.edu.co.

bUniversidad Simón Bolívar, Barranquilla, Colombia. E-mail: crodriguez29@unisimonbolivar.edu.co.

cUniversidad del Norte, Barranquilla, Colombia. E-mail: arey@uninorte.edu.co.

Received: September 30, 2016. Accepted: March 28, 2017.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Jiménez, M., Rodríguez, C., & Rey Paba, L. (2017). Standardized test results: An opportunity for English program improvement. HOW, 24(2), 121-140. http://dx.doi.org/10.19183/how.24.2.335.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. License Deed can be consulted at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This case study explores the relationship between the results obtained by a group of Industrial Engineering students on a national standardized English test and the impact these results had on language program improvement. The instruments used were interviews, document analysis, observations, surveys, and test results analysis. Findings indicate that the program has some weaknesses in terms of number of hours of instruction, methodology, and assessment practices that affect the program content and the students’ expected performance. Recommendations relate to setting up a plan of action to make the program enhance student’s performance in English, bearing in mind that the goal is not the students’ preparation for the test but the development of language skills.

Key words: Common European Framework of Reference, curriculum, standardized tests, SABER PRO test, washback effect.

Este estudio de caso explora la relación entre los resultados en las pruebas obtenidos por unos estudiantes de ingeniería industrial en un examen nacional de inglés y su impacto en el mejoramiento de un programa de inglés. Los instrumentos usados fueron entrevistas, análisis documental, observaciones, encuestas y análisis de los resultados de los exámenes. Los resultados indican que el programa tiene debilidades como número de horas y prácticas metodológicas y de evaluación que afectan los contenidos del programa y el desempeño de los estudiantes. Las recomendaciones se relacionan con acciones a tomar para mejorar el programa, y por ende el desempeño de los estudiantes ya que la meta no es la preparación para el examen sino el desarrollo de competencias en inglés.

Palabras clave: curriculo, efecto de rebote, Marco Común Europeo de Referencia para las Lenguas, pruebas SABER PRO, pruebas estandarizados.

Introduction

Establishing a relationship between a language curriculum and students’ performance on national standardized tests is not a common research topic in Colombia. However, more and more frequently, national standardized tests are becoming an important tool to measure program accountability, and even to evaluate the quality of education in this country. Given this new reality, both public and private universities have started to look carefully at the results obtained by their students on these tests in order to identify areas in need of improvement. This research will focus on how these results can be used to inform decision-making processes in an English program at a university.

Being bilingual has become relevant in these times. As Sánchez (2013) explains: “The linguistics abilities are one of the key factors for the development of society (p. 3)” leading to the establishment of public foreign language policies. English has stepped in as the chosen language for these policies. In that sense, Graddol (2006) says that “English is the global lingua franca and it has a great impact on the ecomomic growth of society (pp. 58-63).” Furthermore, Sánchez (2013) points out that English is important in education as the best universities of the world are located in English-speaking countries. He adds that “English is one of the official languages for the United Nations and for the International Monetary Fund (p. 4).” [authors’ translation]

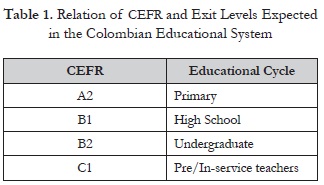

As a result, the Colombian Ministry of Education (MEN) designed a program to enhance English language learning in the country. This program has been in place since 2005, and has experienced several changes since its implementation. The program adopted the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) (MEN, 2006) as the benchmark for determining the language level attained by students in the different cycles of the Colombian educational system. Based on the CEFR, students finishing their tertiary studies should demonstrate a B2 level of the language (MEN, 2014). In order to confirm that this goal has been met, the MEN uses the SABER PRO test. This test evaluates general and field related competences. The English component of this test gives students’ results in terms of the CEFR. Test results, in general, are used by the MEN to rank universities through the Model of Education Performance Indicators (MIDE). Due to this ranking system, results are becoming an important source of information for universities to design action plans for improvement in the different academic/content areas the test evaluates.

In the scarce literature on the topic, three studies (Alonso, Martin, & Gallo, 2015; Benavides, 2011; MEN, 2014) show an analysis of the SABER PRO results in four important cities in Colombia. These studies reported that the majority of undergraduate students who took this test in 2011 and 2012 placed in the A1 and -A levels after having completed their university English courses. The first study (Benavides, 2011) shows that 80% of the students reached the A1 or -A level, while only 20% obtained a level of B1 or B2. The second study (Alonso et al., 2015) presents a historical analysis from 2009 to 2012, which reveals information similar to Benavides’ study (2011); it confirms that the majority of students were placed in the A levels. The B1 and B2 levels were reached by lower percentages of students. The MEN (2014) also carried out a study and found out that only 8% of university students reach the expected B2 proficiency level. This study also showed that the number of students reaching the B+ (B2, C1, and C2) level only increased by 2% in the period between 2012 and 2014 while the number reaching the B1 level decreased by 2%. Likewise, it showed that only 1% of the students that placed in A- moved to the A1 level in 2012.

The context where this research project took place shows similar results to the ones presented above. Academic authorities from this private university considered that it was important to analyze the reasons why, after completing their six-level English program, students do not perform as expected on the national standardized test. Taking into account that the curriculum offers a communicative language approach, which implies real meaning, the test focuses on the same path. In other words, the test is our curriculum. For this study, the participating students belong to the Industrial Engineering program. This article, briefly, describes the theoretical foundations of the study; second, it presents the research methodology used; then, it reports on the results of the study which analyzed the English language curriculum and how this affects the students’ performane on a national standardized test; and finally, it proposes ways to start taking new directions for the program under review.

Literature Review

Evaluation

As the focus of this study refers to standardized test results, it is relevant to define the concept of evaluation. Evaluation entails an integral process that requires the participation of all the members of the learning process.

Second language evaluation involves many different kinds of decisions related to the placement of individual students in particular levels or courses of instructions; about ongoing instruction; about planning new units of instructions and revising units that have been used before; about textbooks or other materials; about students’ homework; about instructional objectives and plans; and about many other aspects of teaching and learning. There is more to evaluation than grading students and deciding whether they should pass or fail. (Genesee & Upshur, 1996, p. 3)

This reflection is important as evaluation cannot be seen as a final product (the grade) but rather as the result of a process (the learning).

Evaluation is much more than simply giving a mark or gathering information about a task completion. It is a judgement regarding the information collected through the results obtained. This is why using results of standardized tests may seem unfair to students as this type of exam gives them only one chance to demonstrate what they have learnt without taking into account other aspects.

Evaluation is a very complex process that implies teachers’ and adminstrators’ awareness in order to understand the results gathered and set appropriate criteria in order to make decisions.

Information, interpretation, and decision-making are three components of the evaluation process. The information alone is not relevant, but at the moment of interpreting it, it opens lights to make assertive decisions towards the actions that must be done and the changes that need to be implemented in order to improve the learning process (Genesee & Upshur, 1996. p. 4)

Therefore, it would be important to analyze why students are not getting the expected results and what is affecting their performance on the test.

Standardized Testing

Bond defines standardized testing as tests that are applied and scored in a uniform way (1996). Davies et al. (2002) stated that

this kind of test must have a religious development, trialing and revision process. Questions must be consistent and the procedures for administering the test must follow specific rules in order to ensure that all the participants who are going to take the test have the same conditions. Besides, the test content must fulfill a set of test specifications and reflect a theory of language proficiency. (p. 187)

Standardized tests include norm-referenced and criterion-referenced tests. Norm-referenced tests are generally employed “to identify those students [sic] with special needs” (Graham & Neu, 2004) and criterion-referenced tests “are used to assess a student’s mastery of the curriculum and to evaluate teacher and school effectiveness” (p. 296). The SABER PRO test can be classified as a criterion referenced test. Below is a description of the test.

SABER PRO

The SABER PRO is defined on the ICFES website (http://www.icfes.gov.co) as “the Colombian state examination of the quality of Higher Education.” It is is part of a group of instruments to exercise government inspection and supervision of the educational field. This exam evaluates generic and field related competences developed by the students as well as their English language level. As the Colombian government decided to adopt the CEFR, the English component provides students’ results in terms of this scale. The English section of the exam is composed of 35 questions to be answered in 60 minutes, and the questions are organized into five parts. In these parts, students find multiple choice, matching, conversation completion, and fill-in-the-blank exercises.

However, the test only measures reading, grammar, and vocabulary skills. This implies that the results do not show the overall proficiency level of the students as speaking, listening, and writing are not evaluated. This may give an incomplete picture of students’ real language level and as test results are used as an indicator of the internationalization component in the above mentioned MIDE strategy, universities that obtain lower results could potentially make curricular decisions to focus their language programs only on the skills evaluated by the test.

The Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR)

According to the Council of Europe (2001), the CEFR “describes in a comprehensive way what language learners have to learn to do in order to use a language for communication and what knowledge and skills they have to develop so as to be able to act effectively” (p. 1). This framework establishes six levels of proficiency that indicate how learners advance in the language learning process.

Furthermore, this framework has common reference points that permit a clear description of each level. In other words, Martyniuk (2010) states that “the CEFR is a concertina-like reference tool that provides categories, levels, and descriptors that educational professionals can merge or subdivide, elaborate or summarize, adopt or adapt according to the needs of their context” (p. 3). Institutions use it to make their programs comparable to others and share common and clear criteria for curriculum design and student learning assessment. When the MEN adopted the CEFR in 2005, it established its levels as the exit goals for the different cycles of the Colombian educational system. Table 1 shows this relation.

Although it is important to analyze the data obtained from standardized tests, it is also important to bear in mind that making decisions based only on these results can be counterproductive for the language program. That is why we need to be aware of what the washback effect is and how it can affect language programs.

The Washback Effect

In curriculum design and assessment, it is relevant to study the washback effect that can affect academic programs after the analysis of standardized tests results. Washback refers to the impact the standardized test results have on curriculum and classroom practices. The washback effect is described as

A natural tendency for both teachers and students to tailor their classroom activities to the demands of the test, especially when the test is very important to the future of the students, and pass rates are used as a measure of teacher success. This influence of the test on the classroom is, of course, very important; this . . . effect can be either beneficial or harmful. (Buck, 1998, p. 17)

As explained before, the results of the SABER PRO are used as a tool to measure the quality of Colombian universities. This has caused institutions to analyze why these results are obtained and what curricular adjustments are needed, so students will perform better.

According to Shohamy (as cited in Green, 2007), “washback is an intentional exercise of power over educational institutions with the objective of controlling the behavior of teachers and students” (p. 2). In addition, Messick (as cited in Barletta & May, 2006) claims that

if a test is deficient because it has construct underrepresentation, then good teaching cannot be considered an effect of the test, and conversely, if a test is construct-validated, poor teaching, cannot be associated with the test. Only valid tests (which minimize construct underrepresentation and construct irrelevancies), can increase the likelihood of positive washback. (p. 237)

Alderson and Wall (as cited in López, 2002) define washback as the effects that tests have on teaching and learning.

Institutions tend to use several washback strategies such as definition of teaching pedagogy, selection of textbooks (Xie, 2013), curriculum review, and test preparation courses.

It is a very common practice for institutions to offer short courses that were defined by Messick (1982) as “any intervention procedure specifically undertaken to improve test scores, whether by improving the skills measured by the test or by improving the skills for taking the test, or both.” (p. 70). These courses intend to familiarize students with the structure of the test, the types of questions, and how to select their responses in a timely manner. This practice may have negative and positive consequences for students. On the other hand, this practice does not guarantee that students will perform well on the test. For instance, this type of course focuses on providing students with strategies for selecting the correct answers, reviewing language, and familiarizing students with test formats. Also, these courses do not prepare students to handle the stress of doing well on the test and imply, in some cases, using class time to practice the test (Jin, 2006).

However, preparing students for the test may also have positive consequences. Some studies (Messick, 1982; Powers, 1985; Powers & Rock, 1999; Xie, 2013) show that this practice could improve test results, but on a small scale. Benefits found relate to students learning how to handle long and complex written texts, how to use time effectively, and how to identify the correct answer timely.

Furthermore, the washback effect can also make the mismatch between the program and the test goals more evident. As stated before, the SABER PRO exam does not test all four language skills that most language programs aim to develop in students. This can lead to course objectives being neglected by teachers in order to focus on the skills evaluated by the test.

Type of Study

This research paper follows a case study design. According to Rowley (2002),

the most challenging aspect of the application of case study . . . is to lift the investigation from a descriptive account of “what happens” to a piece of research that can lay claim to being a worthwhile, if modest addition to knowledge. (p. 16)

In other words, the case study design suits this study because it helps the researcher to make connections between what the participants do in their language course and how this is reflected on the standardized test.

This design is also suitable because the study was developed in only one of the undergraduate programs offered in the institution. As Wallace (1998) puts it, this implies the systematic investigation of an individual case that can refer to one person or a group of people that have a common characteristic. In this case, the study focused on a group of engineering students who had already finished their English program and had taken the SABER PRO test. Instruments used were: First, document analysis which in this case was the examination of the program in light of the basis of the CEFR and the Norma Técnica Colombiana (NTC) 5580 (ICONTEC, 2007), which states the main features that any language program must have in Colombia. Second, interviews of the level coordinators on the appreciation they had of the program and the way it was structured and developed as well as the criteria they took into account in order to structure it. Third, six classes observation per level during one semester aimed to identify the features described in the program and the SABER PRO components, as well as surveys given to the students to know the appreciation they had regarding the program, its duration, and the way it was developed. Also included was a statistical analysis of the results of the SABER PRO test using the SABER 11 as the entry reference to be compared with the results obtained by the students on the SABER PRO test. Once the data were collected, results were also triangulated as a way to validate them by looking at the same findings but from different perspectives.

Setting

This research took place at a private university on the Colombian Caribbean coast. This university is a non-profit institution mainly governed by the Normative University studies Framework, and supervised by the MEN. The study was developed with a group of 440 Industrial Engineering students who had completed a six-level English program. The group included 239 women and 201 men.

Most of the students’ ages ranged from 24 to 27 years old. Ninety-six percent of the students belonged to the social strata one, two and three.1 Only 4% was classified in the higher strata (four and five) and no one belonged to the highest (6). Besides, most of the students had finished their high school in a public school in their hometowns. According to the SABER 11 test results, these students generally showed a very poor English level.

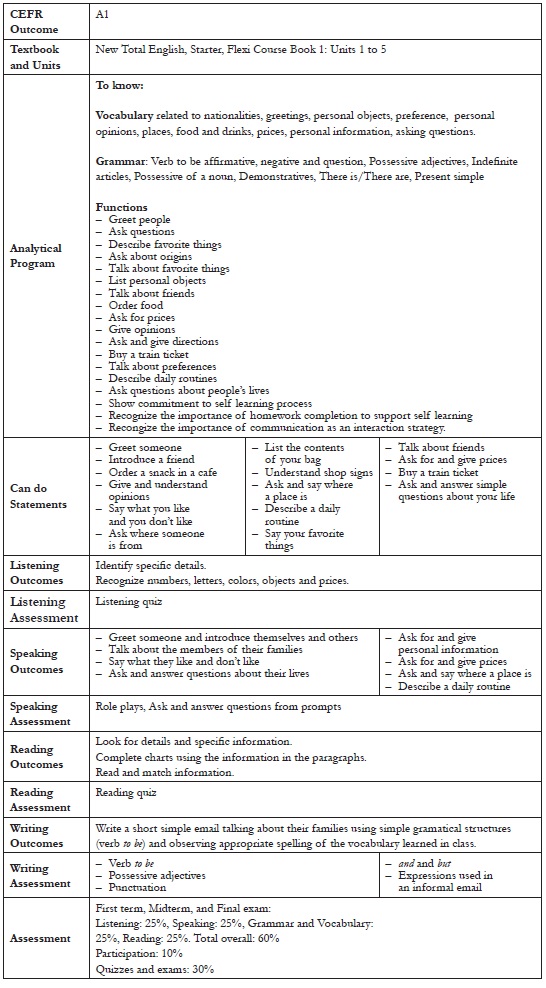

The program is composed of six levels, each with 64 hours of instruction, for a total of 384 hours for all 6 levels combined. These levels are Basic (book starter 1), Intermediate 1 (book starter 2), Intermediate 2 (book elementary 2), Advanced 1 (book pre-intermediate 1), Advanced 2 (book pre-intermediate 2), and Advanced 3 (book intermediate 1). Each level has its own syllabus which is based on the contents of the book (New Total English). It is important to mention that the students have to start the English course in the second semester of the Engineering program and later, they decide the following semesters how to finish them. The final language goal of the program is focused on helping the learners develop the four language skills in English up to a B1 level, according to the CEFR.

Results

The Program

The program offers a general English course. It was analyzed using the CEFR and the NTC 5580 as references. These documents were used as guides to revise learning outcomes, progression of the development of language skills throughout the program, the role of the material in supporting the attainment of the goals, and the appropriacy of the number of hours to reach the expected level. This analysis gave insights about the relationship between the program, the material used, and the CEFR descriptors to establish how these aspects may have affected students’ performance on the SABER PRO test.

The first salient finding is that the course has an appropriate number of hours of instruction to achieve the B1 level, which is its stated language goal. This is deduced from the NTC 5580 that establishes 375 hours of tuition as the minimum required to achieve the B1 level, as shown in Table 2. The program under study offers 384 hours total, implying that according to such number of hours it would be possible to attain the B1 level. However the low level of English the students have when they enter the course is a big constraint to reach the desired B1 level. In fact, it seems that the CEFR offers a description of what an ideal English level could be.

This distribution of hours along the program must be revised since the A1 and A2 levels together require about 200 hours of instruction and the program offers 256 hours in total. On the contrary, the proportion of hours for the B levels is 128 and not the 175 recommended. The NTC indicates that the higher the level, the more hours of tuition are needed.

The Coursebook

Another finding indicates that there is a clear match between the program goals and those proposed by the CEFR. This result is obtained from the comparison of the course syllabi with the CEFR descriptors and the textbook, bearing in mind the British Council EAQUALS core inventory for general English (see Appendix). The analysis showed that the textbook, which is the basis of the curriculum, is aligned with the CEFR descriptors. Therefore, it can be said that there is a logical progression in the language development from level to level. This is to some extent positive because as suggested by Woodward (2001), textbooks need to be a good fit for the language programs. However, this also implies that the program requires a thorough revision because, although it is based on the CEFR, it basically follows the book thus neglecting students’ real needs at the moment of defining learning outcomes and contents. As Valdez (1999) expressed, teachers have to determine what students’ needs are in order to design effective courses.

As Richards (2012) indicates, textbooks have advantages and disadvantages; they give structure to courses and serve as basis for the language input. However, he also points out that they do not always reflect students’ needs and they may present inauthentic language. In sum, the coursebook gives the program a sense of clarity, direction, and provides evidence of learners’ progress. It is a key element in the program but not the program itself. Real learners’ needs have to be the core of curriculum design. Woodward (2001) explains:

The coursebooks can be filled with cardboard characters and situations that are not relevant or interesting to your learners. They have to suggest a lock-step syllabus rather than one tailored to your students’ internal readiness. If the pattern in the units is too samey it can start to get very predictable and boring. (p. 146)

For that reason, it is suitable to design materials that can complement the coursebook. McGrath (2002) affirms that materials for learning and teaching languages could include realia and representations. Those tools can be specially selected and used in order to accomplish the teaching purposes for each specific lesson.

Tasks and Teachers’ Class Actions

Some interesting findings about class activities and teachers’ actions were gathered throughout the application of the instruments. The first instrument was the classroom observation. Six classroom observations were done aimed to identify the features described in the program. Second, the survey of the students to gauge the appreciation they have related to the program: its duration and the way it is developed. Third, the interview of the level coordinators on the appreciation they have of the program and the way it is structured and developed as well as the criteria they took into account in order to structure it.

The first finding is related to the complexity of the tasks proposed by the textbook and expected to be developed in class. When analyzing the textbook and class material, it was possible to determine that the grading and sequencing of these activities were appropriate as these begin with easy-to-complete tasks, and gradually become more complex, lesson by lesson and level by level. It can be said that the complexity goes in accordance with the progression of the language skills and is related to the cognitive, interactive, and learner dimensions of the tasks (Robinson & Gilabert, 2007). According to Robinson and Gilabert, tasks should be “designed, and sequenced” (p. 162) on the basis of their cognitive complexity, which is clearly observed in the materials and classes.

However, class observations revealed that although the activities proposed by the textbook had a more functional language approach, teachers tended to focus more on grammar and not on the functions. This may have an impact on student language as it is believed that learners could achieve better communicative abilities if the instruction they receive resembles a “natural” environment (Lightbown & Spada, 1990). This does not mean that form-focused instruction (FFI) has to be banned from the class. It means that a balance between communivative language teaching and FFI should be reached.

Another finding is related to the role of students’ first language in the classroom. Participant teachers tended to rely heavily on the use of Spanish to facilitate comprehension of the different commands given during the class and even some explanations; that happened not only in the first levels but also in the higher levels of the program. It cannot be denied that the mother tongue has a necessary role in the foreign language class as it gives students a sense of security and acknowledges their experiences (Auerbach, 1993). However, Auerbach suggests that Spanish should have some specific uses such as record keeping, classroom management, language analysis, instructions or prompts, explanation of errors, and assessment of comprehension. Overusing Spanish may affect students’ capacity to use English effectively because this may be the only moment in their daily lives to be in contact with the language and this limited class time is their chance to be exposed to English (Schweers, 1999).

In fact, this type of teachers’ actions goes against one of the premises of the coursebook and the coordinators’ idea that the program follows a communicative approach to language learning. As Richards and Rodgers (1986) explained, this means having a clear idea of “language as communication” (p. 66) and giving more importance to language use rather than to grammar. As stated above, teaching language structure explicitly should not be the center of the process, but, rather, expressing real communicative needs.

Class observations also revealed other actions that may affect language learning. Aspects such as teacher talking time and interaction patterns indicated a very teacher-led and centered class in which students had few opportunities to use the language to express ideas or real needs. In communicative language approaches, both the teacher and the students should have specific roles during the process. Candlin (as cited in Richards & Rodgers, 1986) explained that the learner must be responsible for the process and be active while the teacher must be a mediator and a facilitator of the communication process, contributing to the appropriate development of the learners’ abilities.

In fact, the teachers tended to use the classroom sequence of teacher initiation-response-feedback. This means that students only responded when the teacher asked them. This is a traditional teacher-whole class type of pattern. Very few instances of student-student interaction were observed and the focus of the class was the explicit explanation of grammar. The students’ participation was limited to repeating what the teacher said and not to communicating ideas. As Long (1996) and Pica (1994) suggested, there should be more opportunities for students to negotiate meaning and speak. These classes did not provide students with these opportunities.

Another finding is related to the lack of explicit teaching of reading strategies as well as vocabulary and grammar learning techniques that may help students not only when taking the test but also to enhance their learning. The observations indicated that the teacher does not explain how to use learning strategies to the students during the class. According to Song (1998), strategies should be explicitly taught using direct explanation, teacher modeling, and extensive feedback as these improve students’ reading comprehension skills. Furthermore, there was no evidence of any reading activity implemented or the use of strategies in any of the classes observed. These types of exercises are present in the standardized tests so exposing students to them may help prepare them for the test. According to Krashen and Terrell (1983), language is acquired not through memorization and vocabulary lists or grammar exercises, but through understanding people’s ideas. They added that teaching formal aspects of language is not the primary purpose of language education but to help learners understand, communicate, and function successfully in the language.

These findings may indicate the need for implementing a necessary process of teacher professional development to discuss theoretical and practical aspects of the English class. As suggested above, faculty development can include a formal observation process as this can lead to improvement in teachers’ class actions and decisions. Bell and Mladenovic (2008) consider that peer observation helps teachers to better their practice and even change their perspectives about education.

Standardized Test Results

An important source of study for this research was the analysis of the standardized test results. As stated before, the results analyzed belonged to a group of 440 Industrial Engineering students. The data analyzed covered the first semester of 2011 up to the second semester of 2014.

The first analysis established the level in which each student started the program when they entered the university. The SABER 11 results were taken as the entry point. In order to determine how students’ level changed because of their pariticipation in the language program, the SABER PRO test results were taken as the exit point of the process. Both standardized tests are mapped to the CEFR and are administered by the MEN.

The comparison of these two tests reflected that a high percentage of the students (88.8%) started in the lower levels (A1 and -A1). When comparing these entry results to the exit ones, there is evidence of a slight movement upwards in the CEFR scale. The most striking result is that 54.9% of the students exit the program with an A1 level after having completed the six levels. This is followed by 22.6 % of the students who moved up to the A2 while 14.7% got B1, and 7.8% a B+. The second important result is that through the years (2011-2014), the A2 level has been increasing while the B1 is decreasing. These results are coherent with Benavides (2011), Alonso et al. (2015), and MEN (2014) studies.

This leads us to assume that the students who completed the program advanced in their learning process although such progression is not significant in terms of the levels achieved in the CEFR. A possible cause of this may be related to the level with which students access the course. In the SABER 11 analysis, it was evident that students’ language entry level was low. According to Abedi (2002), “the language background of students may add another dimension to the assessment outcome” (p. 231) which would imply that the program does not satisfy the language and learning needs of the students that entered the program with a -A1. This may imply that a restructuring of the program may be a potential solution as the program could start at a -A1 level to give students the basic foundations of the language.

These decisions would have a profound impact on the program and the administrators would have to balance pros and cons of all the implications that any change may entail. Also, and bearing in mind the aforementioned positive washback effect, there is a need to include explicit reading strategies teaching, foster teacher development, and devote some hours to familiarize students with the structure of the tests and the types of questions they will encounter in them.

Conclusions and Recommendations

This study attempted to trigger the discussion about the effect of standardized test results in language curriculum evaluation. There is not much research on the topic and this was one of the limitations of the study. If there were more research, the relation between test results and language programs could be more effectively used to help learners, teachers, administrators, institutions, and the MEN to improve the quality of language learning.

It is also relevant to keep in mind that, although the MEN adopted the CEFR as the most suitable benchmark to establish the students’ exit levels in the national standardized tests, the instrument used to measure these levels (SABER PRO) only assesses reading and language use. This gives an incomplete language profile of the learner, the competences developed, and poses a dilemma to course designers: What is more important: students’ learning or their test results?

Working towards a better student performance on these tests has become an important issue at university level. This has led institutions to initiate plans to help students perform better. However, the use and interpretation of test results need to be objectively done. Decisions have to be made after all the aspects have been taken into account and cannot affect the curriculum negatively. Programs and institutions may need to minimize the negative washback effect in which teachers and program administrators focus on the test and ignore students’ real communicative needs. That is why studies like this are needed so the negative washback can be turned into possible opportunities for program development and planning.

Therefore, institutions need to set up plans in which English language programs are revised in terms of appropriacy of the learning outcomes and its relation to the CEFR, consistent students’ strategy development, clear progression of skill development, pertinent materials, effective teachers’ class actions, and suitable number and distribution of hours of instruction along the program.

If program administrators want to meet the goals set by the MEN and help students develop language skills, they need to carry out periodical self-studies and make coherent decisions to give students and teachers the opportunity to work together towards the common goal. These actions require a critical analysis of what is stated in the curriculum, how it is realized in the classroom, and what is assessed in the tests.

This implies that documents need to be clearly defined and that class actions should be in consonance with more communicative language learning approaches, so students have opportunities to use the language in real life situations. This meaningful use of the language will allow students to face the test with more confidence and make more informed answer selections. Class actions are also related to the interaction patterns the teachers favor in the classroom. Learning experiences where students do not have an active role affect learning. The class needs to be a space for taking risks, in a good sense. That is why teachers need to vary their interaction patterns and promote different ways of collaboration among students themselves and the teacher. These teacher-related decisions can only be achieved through the implementation of teacher development processes where teachers have opportunities to grow together and share professional experiences. Last, although the program should not focus on the test, including elements of test preparation, explicit learning strategies training can give students more chances to perform better.

For this study, the institution where it took place has started a curriculum review process as well as teacher development actions. A closer look at the relation among the curriculum, class actions, and assessments has become the starting point.

Some recommendations resulting from this study are shared here:

(1) Programs should have consistent and continuous self-evaluation processes that include the analysis of the relation between standardized test results and the curriculum. This may result in appropriate decision-making processes for the program bearing in mind the development of students’ language skills and not only their performance on the test.

(2) Programs should also implement teacher development programs where they share their experiences, observe each other, grow together and learn about effective language teaching approaches.

(3) Programs have to include specific test taking skills and student familiarization with test items during the course so they will be prepared to face the challenge of the test. This includes an analysis of the type of questions asked on the test and the type of text types used.

(4) Last but not least, this is also an invitation for scholars to share their experiences and how the results in the standardized tests have affected the curricular decisions they have made.

In sum, conducting this type of study is an opportunity for teachers, program administrators, and program designers to reflect on their own situation and how this discussion can be enhanced.

1In Colombia, the neighborhoods in cities are classified according to similar social and economic characteristics from strata 1 to 6. Stratum one has the lowest income while six has the highest.

References

Abedi, J. (2002). Standardized achievement tests and English language learners: Psychometrics issues. Educational Assessment, 8(3), 231-257. http://doi.org/10.1207/S15326977EA0803_02.

Alonso, J. C., Martin, J. D., & Gallo, B. (2015). El nivel de inglés después de cursar la educación superior en colombia: una comparación de distribuciones [English proficiency in Colombia after post-secondary education: A relative distribution analysis]. Revista de Economía Institucional, 17(33), 275-298. http://doi.org/10.18601/01245996.v17n33.12.

Auerbach, E. R. (1993). Reexaming English only in the ESL classroom. TESOL Quarterly, 27(1), 9-32. http://doi.org/10.2307/3586949.

Barletta, N., & May, O. (2006). Washback of the ICFES Exam: A case study of two schools in the Departamento del Atlántico. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 11(1), 235-261.

Bell, A., & Mladenovic, R. (2008). The benefits of peer observation of teaching for tutor development. High Education, 55(6), 735-752. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-007-9093-1.

Benavides, J. E. (2011). Las pruebas estandarizadas como forma de medición del nivel de inglés en la educación colombiana [Standardized tests as measurement for the level of English in Colombian education]. En J. Bastidas & G. Muñoz (Eds.), Fundamentos para el desarrollo profesional de los profesores de inglés (pp. 19-24). San Juan de Pasto, CO: Graficolor.

Bond, L. A. (1996). Norm- and criterion-referenced testing. Retrieved from ERIC database. (ED410316)

Buck, G. (1988). Testing listening comprehension in Japanese university entrance examinations. JALT Journal, 10(1), 15-42.

Council of Europe. (2001). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, evaluation (Instituto Cervantes, Trans.). Madrid, ES: Ministerio de educación, cultura y deporte.

Davies, A., Brown, A., Elder, C., Hill, K., Lumley, T., & McNamara, T. (2002). Dictionary of language testing. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Genesee, F., & Upshur, J. A. (1996). Classroom-based evaluation in second language education. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Graddol, D. (2006). English next. London, UK: British Council.

Graham, C., & Neu, D. (2004). Standardized testing and the construction of governable persons. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 36(3), 295-319. http://doi.org/10.1080/0022027032000167080.

Green, A. (2007). IELTS washback in context: Preparation for academic writing in higher education. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

ICONTEC. (2007). Norma Técnica Colombiana 5580. Bogotá, CO. Retrieved from http://www.mineducacion.gov.co/1621/articles-157089_archivo_pdf_NTC_5580.pdf.

Jin, Y. (2006). Improving test validity and washback: A proposed washback study on CET4/6. Foreign Language World, 6, 65-73.

Krashen, S. D., & Terrell, T. D. (1983). The natural approach: Language acquisition in the classroom. San Francisco, US: Pergamon/Alemany Press.

Lightbown, P. M., & Spada, N. (1990). Focus-on-form and corrective feedback incommunicative language teaching. Studies in second language acquisition, 12(4), 429-448. http://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263100009517.

Long, M. H. (1996). The role of linguistic environment. In W. C. Ritchie & T. K. Bhatia (Eds.), Handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 413-468). San Diego, US: Academic Press.

López, A. (2002). Washback: The impact of language tests on teaching and learning. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 4, 50-63.

Martiyniuk, W. (2010). Studies in language testing aligning tests with the CEFR: Reflections on using the Council of Europe’s draft manual. Cambridge, UK: Cambrigde University Press.

McGrath, I. (2002). Materials evaluation and design for language teaching. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press.

Messick, S. (1982). Issues of effectiveness and equity in the coaching controversy: Implications for educational and testing practice. Educational Psychologist, 17(2), 67-91. http://doi.org/10.1080/00461528209529246.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional, MEN. (2006). Estándares básicos de competencias en lenguas extranjeras: inglés [Basic standards of competences in foreign languages: English]. Bogotá, CO: Imprenta Nacional.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional, MEN. (2014). Colombia Very well! Programa Nacional de Inglés 2015-2025 (Documento de socialización). Bogotá, CO: Author. Retrieved from http://www.colombiaaprende.edu.co/html/micrositios/1752/articles-343287_recurso_1.pdf.

Pica, T. (1994). Research on negotiation: What does it reveal about second-language learning conditions, processes, and outcomes? Language Learning, 44(3), 493-527. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-1770.1994.tb01115.x.

Powers, D. E. (1985). Effects of test preparation on the validity of a graduate admissions test. Applied Psychological Measurement, 9, 179-190. http://doi.org/10.1177/014662168500900206.

Powers, D. E., & Rock, D. A. (1999). Effects of coaching on SAT I: Reasoning test scores. Journal of Educational Measurement, 36(2), 93-118. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-3984.1999.tb00549.x.

Richards, J. C. (2012). The role of textbooks in a language program. Retrieved from http://www.professorjackrichards.com/wp-content/uploads/role-of-textbooks.pdf.

Richards, J. C., & Rodgers, T. S. (1986). Approaches and methods in language teaching. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Robinson, P., & Gilabert, R. (2007). Task complexity, the cognition hypothesis and second language learning and performance. IRAL, 45(3), 161-176. http://doi.org/10.1515/iral.2007.007.

Rowley, J. (2002). Using case studies in research. Management Research News, 25(1), 16-27. http://doi.org/10.1108/01409170210782990.

Sánchez Jabba, A. (2013). Bilingüísmo en Colombia [Bilingualism in Colombia]. Cartagena de Indias, CO: Centro de Estudios Económicos Regionales, Banco de la República.

Schweers, W. C., Jr. (1999). Using L1 in the L2 classroom. English Teaching Forum, 37(2), 6-9.

Song, M.-J. (1998). Teaching reading strategies in an ongoing EFL university reading classroom. Asian Journal of English Language Teaching, 8(1), 41-54.

Valdez, M. G. (1999). How learners’ needs affect syllabus design. English Teaching Forum, 37(1).

Wallace, M. J. (1998). Action research for language teachers. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Woodward, T. (2001). Planning lessons and courses: Designing sequences of work for the language classroom. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511732973.

Xie, Q. (2013). Does test preparation work? Implications for score validity. Language Assessment Quarterly, 10(2), 196-218. http://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2012.721423.

The Authors

Maureyra Jiménez is an English teacher at Instituto de Lenguas Extranjeras at Universidad Simón Bolivar and holds a master degree in Teaching English.

Caroll Rodríguez is an English teacher at Instituto de Lenguas Extranjeras at Universidad Simón Bolivar and holds a master degree in Teaching English.

Lourdes Rey Paba is an English professor, researcher and Department Director at the undergraduate and graduate level in the Department of Foreign Languages at Instituto de Idiomas, Universidad del Norte. Her research interests include curriculum development, internationalization, language policies, and teacher development. Member of COLCIENCIAS-ranked research group: Language and Education.

Appendix: Sample of Analysis of the Program, the CEFR Level, and the Textbook (Basic Level)