https://doi.org/10.19183/how.25.1.355

Carlo Granados-Beltrána

aInstitución Universitaria Colombo Americana ÚNICA, Bogotá, Colombia. E-mail: c.granados@unica.edu.co

Received: March 6, 2017. Accepted: August 23, 2017.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Granados-Beltrán, C. (2018). Revisiting the need for critical research in undergraduate Colombian English language teaching. HOW, 25(1), 174-193. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.25.1.355.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. License Deed can be consulted at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This article shares a reflection based on the relations found between the partial findings of two on-going projects in a BA program in bilingual education. The first study is named Critical Interculturality in Initial Language Teacher Education Programs whose partial data were obtained through interviews with four expert professors of Licensure programs across Colombia. The second project is Estado del Arte de los Trabajos de Grado 2009 - 2016, which involved an inventory of the theses done by students as graduation requirements for the BA program. Based on these data, the article urges a re-assessment of criticality in research at the undergraduate level by problematizing the hegemonization of action research, the instrumentalization of language and research, and the subalternity for those being researched.

Key words: Action research, critical theory, decolonial option, research in English language teaching, undergraduate programs.

Este artículo es una reflexión acerca de las relaciones entre los hallazgos parciales de dos investigaciones en curso en una licenciatura en educación bilingüe. En el primer estudio, La interculturalidad crítica en los programas de formación inicial de docentes de lenguas extranjeras, parte de los datos surgieron de entrevistas con cinco profesores expertos de licenciaturas de distintas zonas de Colombia. El segundo, Estado del arte de los trabajos de grado 2009 – 2016, es un inventario de las tesis desarrolladas como requisito de grado para la licenciatura en educación bilingüe. El artículo insta a una re-evaluación de la criticidad en la investigación en los pregrados en enseñanza de inglés al problematizar la hegemonización e instrumentalización del método de investigación-acción y la subalternización de los investigados.

Palabras clave: investigación-acción, investigación en pregrados en enseñanza de inglés, opción decolonial, teoría crítica.

The purpose of this article is to share a reflection exercise emerging from a comparison between two sets of data obtained from two on-going research projects in a BA program in bilingual education. The first set was obtained from a group of four expert professors from licensure programs across Colombia interviewed for a doctoral project entitled Critical Interculturality in Initial Language Teacher Education Programs. The second set was obtained from Estado del Arte de los Trabajos de Grado 2009 - 2016, which accounted for the theses developed by students in the BA program in bilingual education. This paper urges a reassessment of critical approaches to research in the field of English language teaching (ELT) in undergraduate programs in Colombia to better respond to the current situation of the world and the country, to national language policies, and to the kind of research most commonly promoted in teacher education programs at undergraduate levels.

Bauman and Giddens (as cited in Portera, 2011) stated that postmodernism has contributed to “an inward-looking human being, a person imbued with an individualistic and narcissistic attitude, self-centred, material goods and quantity-oriented (to the detriment of quality), with a volatile and erratic nature” (p. 13). This phenomenon, he argues, has affected educational systems since strategies, curricula, and methods are revised superficially, originating technical solutions which are stripped of clear objectives and solid moral principles; thus, in a time of uncertainty, fragmented life, weakened authority, and a culture of economic force redefining educational goals is needed.

The acquisition of goods and skills, just for their own sake, seems to be what leads the current world, instead of the construction of a better world by the overcoming of conflict and the creation of beauty (Phipps & Levine, 2012). Language pedagogy is not the exception; nowadays, it is focused on the meeting of standards which represent a certain level of acquisition of that skill. However, language pedagogy has an ethical goal that goes into the construction of intersubjective meanings that help us both to understand ourselves and others in the interest of better societies.

As for Colombia, we have experienced a plebiscite for a peace agreement with a high degree of abstention and a negative result due to manipulative leadership, which questions the existence of an informed citizenship. Nonetheless, we are moving into a post-conflict society where interacting with different actors, preventing confrontations, and assertive communication become paramount. Additionally, in relation to language pedagogy, there is an increasing concern about the importance of mother tongue literacy for bilingual processes, as expressed by Araújo and Corominas (1996), Bermúdez, Fandiño, and Ramírez (2014), and Maturana (2011). In the same way, De Zubiría (2014, 2016) has constantly questioned the real need to become proficient in English when students lack skills in mother tongue literacy and citizenship.

Based on the scenario described, I will start the paper by discussing the tenets proposed by Kincheloe and McLaren (2005) to establish a link between critical theory and qualitative research. After that, I will describe some critical aspects of ELT and, specifically, Colombian ELT based upon the proposal of a decolonial option (Kumaravadivelu, 2016). Then, I will present the reasons I perceive for a reassessment of critical approaches by emphasizing three aspects: (1) the problems caused by a hegemonic notion of action research as the research methodology for ELT contexts, as experienced in licensure programs, (2) the need for a horizontal approach to research (Corona Berkin & Kaltmeier, 2012) that accounts for the participants’ stories and voices, and (3) a renewed idea of critical English language teachers as power-literate (Kincheloe, 2004) professionals, able to work out the malleable dynamics of power in order to move beyond denouncing the problems to start intervening them.

“New” Principles for Critical Theory

I should first clarify that the word new has quotation marks because the principles discussed by Kincheloe and McLaren (2005) are not exactly new. Instead, these principles are a consolidation of different branches of critical theory with an update for the current world. For the sake of brevity, I will only discuss seven of the tenets proposed: (a) the nature of the researcher, (b) a critique to technical or instrumental rationality, (c) the immanence of critique, (d) a constant questioning of ideology, (e) problematizing linguistic and discursive power; (f) an interest in the connection among culture, power and domination; and (g) cultural pedagogy.

In this critical theory update, researchers are intellectuals focused on gauging their work towards social critique based on the idea that any thought is mediated by power relations which are socially and historically constructed. Kincheloe and McLaren (2005) also state that the purposes of critical researchers go beyond mere description and interpretation to potential political actions; and therefore, they are always on the lookout for new theoretical perceptions which help them comprehend the dynamics of power and oppression and how they shape daily life and human experience.

Critical theory also questions technical rationality as a form of alienation in which means are prioritized over ends, leading to an extreme emphasis on method and efficiency rather than on purpose and consequence; thus, key topics are related to the how, instead of the why. Kincheloe and McLaren (2005) critique how this rationality pervaded research in such a way that there is an extreme concern for methods, techniques, and efficiency as a substitute for its more humane purposes.

Critical researchers would have to be worried not only about what is, but also about what should be; this is the immanence of critique. Researchers with a critical view aim their studies to trigger social reform instead of just describing the problem. In this sense, they are concerned about overcoming egotism and ethnocentrism to foster new kinds of relationships among diverse people and groups. Immanence in the context of critical research implies the use of human knowledge to create a better and fairer world, with less suffering and more individual satisfaction (Kincheloe & McLaren, 2005).

Ideological hegemony, another aspect in this renewed critical theory, refers to cultural forms, meanings, rituals, and representations which produce consent of the status quoand the particular places of individuals within it (Kincheloe & McLaren, 2005). This ideological hegemony is not immediately observable, but it is composed of premises that become part of common sense; moreover, when critiquing hegemony, an exploration of the different ways of resistance exercised by subjects is also undertaken.

In critical theory, language is not conceived as objective or neutral; on the contrary, linguistic descriptions contribute to construct realities by means of discursive formations (Foucault, 2002) which contribute to their regulation and domination. They exemplify how discourses contribute to regulation: “in educational contexts . . . legitimate power discourses say insidiously to educators what books students can read, which instructional methods can be used and which systems of belief and visions of success can be taught” (Kincheloe & McLaren, 2005, p. 310).

Culture in this version of critical theory is a site of power struggle among different groups both dominant and subordinated by the production and transmission of knowledge. It is acknowledged that each culture possesses its own systems of meaning that are products of diverse ways of knowing produced in their specific contexts. Lastly, cultural pedagogy is understood as helping individuals notice the ways in which cultural agents produce hegemonic forms of seeing (Kincheloe & McLaren, 2005). This implies the problematizing of media as new educators contributing to the construction of hegemonic representations and meanings that ought to be questioned through a literacy of power (Kincheloe, 2004).

After presenting these tenets of critical theory, I will continue by discussing the connection between these principles and the decolonial option for ELT discussed by Kumaravadivelu (2016) and how this could serve as a guide for analysing the context of ELT in Colombia at the undergraduate level.

Critical Aspects in ELT and Colombian ELT

The decolonial turn was developed by Latin American theorists to problematize the vestiges of the colonial past of Latin American countries. The authors belonging to this group (Castro-Gómez, 2005; Dussel, 2000; Grosfoguel, 2006; Lander, 2000; Mignolo, 2000, 2001, 2003, 2005, 2007a, 2007b, 2010; Quijano, 1992; and Walsh, 2005, among many others, argue that the effects of European colonization in the Americas can be traced up to the present day; these effects constitute what they name coloniality, which is divided into three dimensions: coloniality of knowledge, coloniality of being, and coloniality of power (Restrepo & Rojas, 2010).

Walsh (2005) asserts that the coloniality of knowledge should be understood as the repression of other ways of producing knowledge different from the white European scientific one. Restrepo and Rojas (2010) also describe some geopolitics of knowledge resulting in a peripheralization of some places and the centralization of others which lead to the subordination of non-Western knowledges and their labelling as folkloric, magic, or alien to expert discourse.

The second dimension, coloniality of being, aims at the subaltern condition ascribed to the subjects from these former colonies, contributing to a maintenance of a complex of inferiority and the search to fulfil the European ideal of race, gender, class, and sexual orientation. Restrepo and Rojas (2010) state that the coloniality of being is the ontological dimension of the coloniality of power in which certain people are constructed as inferior or non-human based on their positioning in the colonial world-system. This means that, based on the European history of Asia, Africa, and Latin America, the idea of being is only embodied in the white European post-Renaissance man (Mignolo, 2001), while populations from other regions make up part of a marginal ontology or their existence is suppressed.

Finally, the third dimension embeds the other two; coloniality of power aims to describe, but also, to subvert the mechanisms by which subalternity is enforced and kept, including social, economic, and political conditions as well as cultural conditions, usually constructed by means of discourse formations that become commonsensical truths. Quijano (1992) explains that the colonial power structure did not disappear with the end of colonial times; on the contrary, this structure remains as the framework in which social relations operate; thus, leading to a set of social discriminations. Walsh (2009) describes the coloniality of power as founded on a racialized hierarchy and on the assumption of a natural superiority justified by the dichotomies of East-West, primitive-civilized, irrational-rational, non-human-human, magical/mythical-scientific, and traditional-modern.

Kumaravadivelu (2016) discusses the problems of coloniality in ELT and urges the enactment of a decolonial option. He describes three problems in relation to coloniality: native speakerism, hegemonic methods and materials, and non-native English speaking teachers as subaltern professionals. Native speakerism refers to the mistaken idea that only the people who speak an ideal English language variety, usually British pronunciation or standard American English, could be the models to follow for English language learners, and that, due to their proficiency in the language, those native speakers are the ones entitled to teach it; therefore, contributing to maintain a coloniality of being. Native speakerism has been increasingly questioned. Rampton (1990), Medgyes, (1992), Moussu and Llurda, (2008), Faez (2011), and Viáfara (2016), among many others, have problematized the lack of correlation between teaching skills and nativeness, the unreality of setting native speaker proficiency as a goal for foreign language speakers, the unfair classification that nativeness and non-nativeness create, and the inadequacy future language teachers in peripheral countries may feel due to native speakerism.

The dimensions of coloniality interplay with one another; therefore, the coloniality of being is linked with the coloniality of knowledge. In this sense, for example, González (2010, 2012) discusses academic colonialism present in Colombian ELT, when teachers’ and teacher educators’ local knowledge is displaced by foreign agencies and editorial companies whose native speakers design, train, and certify non-native teachers. In this way, non-native teachers are constructed as flawed for not speaking as natives and as subaltern professionals for not using methods coming from central English-speaking countries, such as the USA or the UK.

The next problematic aspect, named by Kumaravadivelu (2016) as methods and materials of marginality, is related to the hegemonic idea of applying methods and materials developed in inner-circle countries, such as the USA or the UK (Kachru, 1990), for instance, in the use of the communicative approach and its derivations for ELT in diverse territories, independently of the sociocultural conditions of the contexts. This pervasiveness of the communicative approaches is enhanced, argues Kumaravadivelu (2016), by centre-based textbook editorials which foster the use of certain methods and techniques by means of training sessions offered by the editorials for using the books. This phenomenon is related to both coloniality of power, since local editorials cannot always compete with the centre-based editorials (English or American), and to coloniality of knowledge since only one type of knowledge in relation to language teaching is accepted, that is, the one produced in inner-circle countries.

In Colombia, this dimension of coloniality in ELT has been widely studied (Cárdenas, González, & Álvarez, 2010; González, 2007, 2009; González, Montoya, & Sierra, 2002; González & Sierra, 2005). These authors question the training workshops offered by international editorials based on the existence of best practices, usually designed by centre-based experts that, when applied sequentially and timely, would supposedly guarantee excellent results. This fosters an instrumentalization of practice leading to a de-professionalization of language teachers who become consumers rather than producers of knowledge. This final element also leads to the third issue of non-native teachers as subaltern intellectuals. Kumaravadivelu (2016) argues, based on the Gramscian concept of hegemony, that power structures construct subaltern subjectivities through “an ensemble of political, social, cultural, [and] economic relations that weaken [subalterns’] will to exercise their agency” (p. 76). This means that the two previous dimensions of coloniality, their practical elements and their links to the coloniality of power, contribute to construct non-native English speaking teachers as subaltern professionals.

To exercise resistance against coloniality, Kumaravadivelu (2016) states that actions emerging from the subalterns themselves could challenge and change the set of relations that marginalize them; this could happen when subalterns gain critical consciousness and develop a collective will to act. Based on Mignolo’s (2007a) “grammar of decoloniality”, Kumaravadivelu (2016) offers a set of actions for non-native teachers to begin decolonizing ELT. These are, first, preventing research that aims to demonstrate the efficiency of non-native speaking teachers or to compare their efficiency with that of native-speaking teachers; second, designing teaching strategies responsive to the historical, economic, and sociocultural conditions of the contexts and developing materials which are aligned to local conditions and instructional strategies designed by local professionals; third, restructuring teacher education programs so that prospective teachers become producers and not consumers of pedagogic knowledge and materials; and fourth, doing proactive research, which means “paying attention to the local exigencies of learning and teaching, identifying researchable questions, producing original knowledge, and subjecting it to further verification” (Kumaravadivelu, 2016, p. 82).

As can be observed, most of the actions linked to decolonizing ELT are connected to research. However, the argument in this article is that for truly exercising resistance against coloniality, the way we understand research would have to be re-assessed in light of what is understood as critical.

The context where the projects are taking place is a 12-year-old BA program in bilingual education in Bogotá, Colombia. Its goal is to educate future English teachers based upon the philosophy of liberal arts, whose aims are critical thinking, an open mind towards diverse cultures and societies, and integrated knowledge through an interdisciplinary approach to education. As a graduation requirement for the program, students engage in a research project which may or may not be linked to the teaching practicum. The figures mentioned later in the paper relate to a preliminary analysis of these theses in terms of research interests.

The first set of data comes from some interviews with four professors from licensure programmes. I wanted to have a wider view of pre-service teacher education in the country; that is why the teachers interviewed were located in four major cities in Colombia: Medellín, Florencia, Neiva, and Cali. I intended to include some other professors from Bogotá, Tunja, and Pasto; however, when writing this paper, the interviews had not been accomplished. These participants were also selected because of their experience with the national linguistics policies; thus, all of them were or had been engaged in projects about the promotion of bilingualism in their regions.

The second set of data comes from an on-going project by the Research Director(s) of the BA program whose aim is to construct an inventory of the thesis projects to identify trends and gaps, and to help students write their theses by building knowledge on these previous studies. They were classified based on these criteria: Topic, Title, Similarities and Differences with other theses addressing the same issue and Conclusions. The projects selected covered a period of seven years, from 2009 to 2016.

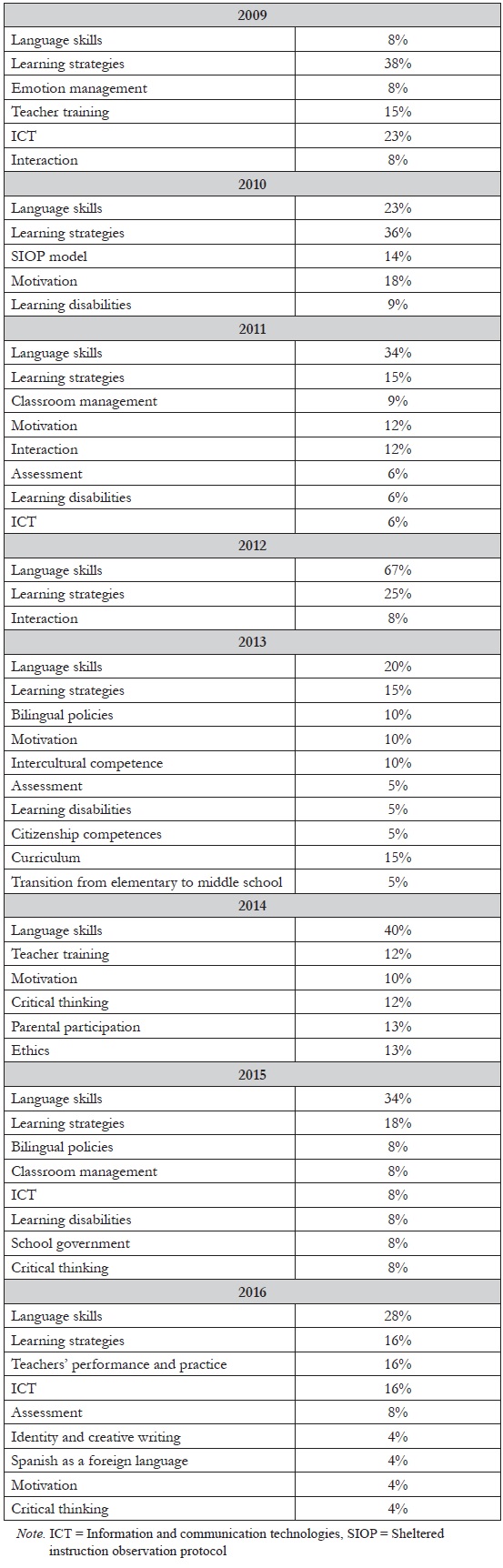

In the project Estado del Arte de los Trabajos de Grado 2009 – 2016 (Dirección de Investigaciones – ÚNICA, 2016), developed by the BA Research Director(s), there was a tendency towards applicationism (Cabra-Torres et al., 2013) noticed in the kind of research questions and topics students pursued. As can be seen in Table 1, there is a continuous interest in inquiring about teaching skills and learning strategies, sometimes in combination, for example, reading improvement through learning strategies, improving proficiency by using songs, movie strategies to acquire English vocabulary, and so on.

Interest in some topics such as motivation, interaction and use of technology remain constant. However, as theses move to wider issues influencing teachers’ work at school, such as critical thinking, bilingual policies, citizenship competences or teaching Spanish, the percentages decrease; yet it is important to highlight the emergence of an incipient interest in intercultural competence, citizenship competence, and learning disabilities, which could possibly indicate a student’s growing concern about these issues.

Table 1. Percentage in Topic Selection in the BA Program

The interviews with the four expert professors were done via Skype. They were interviewed in Spanish; interviews were recorded and subsequently translated and transcribed. These professors expressed some concerns about the ways research is addressed in undergraduate programs, as can be observed in the extracts shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Extracts From the Interviews With Professors (Author’s Translation and Underlining)

After clarifying the methodological aspects of this paper, I will expand on the notion of decolonizing ELT research by de-emphasizing the instrumental nature of both language and research, problematizing the naturalization of hegemonic action research, establishing horizontal relations when doing research, moving from causality to comprehension, and finally, reconstructing the role of local language teachers as public intellectuals (Giroux, 2012).

Tensions in ELT Research

As can be seen in the interview extracts from professors 1, 2, and 4, action research is somehow becoming the default methodology for ELT due to its impact on teaching practice by means of constant reflection about what is done in the classroom. It can also be noticed in the numerous action research books for language teachers (Burns, 1999, 2010; McIntyre, 2000; Mills, 2007; Sagor, 2000; Wallace, 1998; and many others). Kemmis and McTaggart (1988) define action research as

A form of collective self-reflective enquiry undertaken by participants in social situations in order to improve the rationality and justice of their own social or educational practices, as well as their understanding of these practices and the situations in which these practices are carried out. (p. 5)

It is important to emphasize in this definition the elements of rationality and justice of social practice. Latin American pioneers of action research, Fals Borda and Rodrigues Brandão (1987), state that action research is different from other methods due to the collective way in which knowledge is produced and how that knowledge is made collective too. Nonetheless, observing how action research is implemented in the ELT undergraduate contexts, it seems that this method is becoming routinized and therefore, stripped of these characteristics with an emphasis on the instrumentality of both language and research, as I could observe in the theses topics for the BA, which would usually follow a formulaic pattern: how to use X to improve Y, for example: Movie strategies to improve English comprehension and vocabulary, Improving second language proficiency of young learners through songs, Getting the most out of pronunciation through CALL, Mind-mappers and wikis for the improvement of writing skills, among other titles.

Cabra-Torres et al. (2013) in their study about research and innovation in licensure programs contributed two important findings. First, pedagogical practice, which is commonly linked to research in licensure programs, places a strong emphasis on what is practical, represented in the “applicationism”; that is, applying theories, methods, strategies or solutions (Cabra-Torres et al., 2013, p. 338). Second, the authors also argue that there is a lack of articulation between teacher educators in licensure programs and schools, leading to an imposition of explanatory theories of educational phenomena, beyond institutional and existential diversity and complexity in educational practices (Cabra-Torres & Marín, 2015, p. 168). This applicationism can be observed in ELT academic environments, when in academic research encounters, members of the community ask—particularly when the research focus is about a contextual or social pressing concern—How is that used to teach English or “x” aspect of English? Or as exemplified in the kind of inquiry students pursue in the undergraduate program.

The professors interviewed are also critical of different issues related to research on the undergraduate level, as could be seen in Table 2. They name the widespread use of action research to solve classroom problems, and even one of the professors talks about “little projects”resulting from action research. However, they also state having started to teach about some other designs such as case studies, descriptive, exploratory, or correlational studies. Second, Professor 4 questions the technical emphasis on BA research projects which disregard contextual needs. As can be read in the interview extract, he wonders whether licensure programs should take five years to end up continuing research about common topics such as the use of songs to foster oral production, intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, or skills integration, neglecting other concerns related to the characteristics of the population and social conditions influencing language learning.

The routinization of action research in ELT contexts also brings about the issue of ascribing pathologies to school populations, either students or teachers. In the case of initial teacher education programs, this is probably caused by starting an action research project focused on a problem (Burns, 1999; McIntyre, 2000; Wallace, 1998). This leads to three inconveniences I have noticed when guiding students in their projects: first, a mistaken idea of the problem always being something pathological to be solved; second, identifying the problem based solely on the researcher’s view without the participants’ intervention; and third, particularly in the BA programs, attaching an imaginary problem to the population due to time pressures to meet the graduation requirement. What these factors entail is a distortion of the true nature of action research by a strong emphasis on causality (if x action is taken, y should improve) rather than on trying to comprehend participants’ behaviours, contexts, needs, histories, and voices.

Formative research at the undergraduate level needs to address other research questions, even more so due to the current state of the country described before, and manifested in an increasing critique of the national linguistic policies, political debates based on the poor results of the linguistics policy in Bogotá, a hopeful transition to a post-conflict society, and an evident need of an informed citizenry. English as a language cannot be a goal perse, but it can be a means to construct a better society. Along history, different languages played the role English plays today—Greek, Latin, French—then, there is no guarantee that in the future any other language will not replace English as lingua franca; therefore, the goal does not lie exclusively on learning English, or any foreign language, for instrumental purposes. ELT research both at the undergraduate and graduate level in Colombia could become a fertile terrain for both critical education and inquiry which goes beyond the instrumental nature of the foreign language, to rethink it as a means to comprehend other people and contexts as well as the local ones.

Finally, recalling the urge posed by critical research to go beyond contemplation to motivating and—if possible—executing concrete social reforms, it is also important, as mentioned by Professor 3 in the interview, to reflect upon the impact university research has on schools, teachers, and the educational system since it seems there are a lot of descriptions and diagnoses, but there is no follow-up, involvement, or transformation; this means critical researchers and teachers would have to re-assess their role as mere complainants to engage as public intellectuals who become agents of change in their corresponding spheres of influence.

Re-Gaining Criticality in Colombian ELT Undergraduate Research

Based on the dimensions of coloniality—coloniality of being, coloniality of knowledge, and coloniality of power—this section suggests possible initiatives for reinvigorating critical ELT research in Colombian undergraduate contexts. The dimension of coloniality of being could be addressed by creating more horizontal relations between the researcher and researched so that the latter are not deemed unilaterally flawed. Corona Berkin and Kaltmeier (2012) explain that horizontality is an alternative mode of research that intends to reduce power differentials between the researcher and researched. It aims to understand the Other as a subject under construction since the researcher and researched are constituted in one another and the voice of the Other is determined by the one who listens to it in a dialogic context of speaker and listener. This implies that researchers should become aware of their positionalities (Madison, 2012) and how they could be influenced by the constellations of power; that is, how their position is marked by the dynamics and logic of the academic field, which has a high symbolic power and is deeply informed by the coloniality of knowledge (Kaltmeier, 2012). In this way, neither students nor teachers would be ascribed problems that they may not have, but through a horizontal dialogue, researchers would be able to comprehend and transmit participants’ histories and voices.

In relation to the coloniality of knowledge, it would be necessary to boost the transition English teachers are making to research questions of a less technical sort which explore more the links between political, economic, social and cultural conditions, and ELT in Colombia. Also, the selection of action research as a method to carry out inquiry would have to be sheathed again with its critical and participatory features to truly take steps towards the immanence of critique. In addition, to avoid the hegemonization of action research, prospective ELT undergraduate and graduate researchers could appropriate other methodologies that might enrich their understanding of contexts and participants, such as ethnography, phenomenology, narrative research, and case studies, among other possible study designs.

As for the coloniality of power, ELT researchers would need to gain awareness of their role as public intellectuals whose positionality should be integrated by morality, rigor, and responsibility in such a way that their actions enable the emergence of alternative models mediating between higher education and society (Giroux, 2012). Nonetheless, this also means that critical ELT researchers need to discern the dynamics of power to use them to foster their goals. Lukes (1985) described three dimensions of power: the first, when A persuades B to do something s/he wouldn’t normally do; the second, when A establishes for B the rules and outcomes of the game; and the third, when A influences B’s wishes and thoughts to make them want things opposed to their own interests.

It would be important for ELT researchers to be able to wade into these dimensions. As can be seen in the final interview extract from Professor 4, he managed to decide with whom and how to develop his research and educational projects because he had/has constructed a solid professional self, allowing him to determine the rules and goals of his professional activities. Thus, it is important for future language teachers to construct an image as professionals and to become skilful in foreseeing the ideological force of Lukes’s (1985) third dimension of power to avoid being its victims.

Due to the limited nature of the data, it is important to acknowledge that the arguments I make might not be generalizable. However, it is important to recall that the professors interviewed come from different cities in the country and their concerns are similar to the ones I present. Therefore, it would be important to conduct exercises like the one of Estado del Arte de los Trabajos de Grado 2009 – 2016 described here in other undergraduate programs to identify if there have been any changes in the technical nature as regards student research. It would be also important to develop some other interviews with professors from other licensure programs to see if their appreciations about research coincide with the ones shown in the interviews.

This article shared a reflection on the importance of revisiting critical approaches in the field of research in undergraduate ELT due to current world and national changes. The tenets for updated critical research by Kincheloe and McLaren (2005) served as the foundation for exploring Colombian ELT research in the BA programs. One tenet of critical theory is the interpellation it makes to an excessive emphasis on technical rationality; this could be observed in an inventory of BA graduate projects which featured causality, technicality, and language instrumentality, and which followed the method of action research.

Secondly, an updated critical theory problematizes hegemonic ideologies. Action research risks becoming hegemonized as the default methodology for inquiry at the undergraduate level due to the ways it is planned and executed in this academic context. A consequence of action research as a hegemonic ideology is the production of particular places for individuals; in this case, as flawed or possessing x or y problem in undergraduate projects. For example, participants often suffer from lack of proficiency in a skill as well as suffer anxiety, pronunciation mistakes, lack of motivation, lack of vocabulary, and lack of classroom management skills, among many other issues.

Finally, modern critical researchers are intellectuals who focus their work on social critique; it was argued in this paper that it is necessary to recover this role for language educators by becoming power literate and moving beyond contemplation and complaint to more concrete actions, which could be based on a grammar of decoloniality, encompassing new research questions, local materials development, recovery of local pedagogies and practices, and exploration of local contexts and participants.

Araújo. M. C. & Corominas, Y. (1996). Procesos de adquisición del inglés como segunda lengua en niños de 5-6 años de colegios bilingües de la ciudad de Cali. (Unpublished master’s thesis). Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colombia.

Bermúdez, J., Fandiño, Y., & Ramírez, A. (2014). Percepciones de directivos y docentes de instituciones educativas distritales sobre la implementación del Programa Bogotá Bilingüe. Voces y Silencios, 5(2), 135-171.

Burns, A. (1999). Collaborative action research for English language teachers. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Burns, A. (2010). Doing action research in English language teaching: A guide for practitioners. New York, US: Routledge.

Cabra-Torres, F., Herrera, J. D., Gaitán, C., Castañeda-Peña, H., Garzón, J. C., Marín-Díaz, D. L., . . . Jiménez, J. A. (2013). La investigación e innovación en la formación inicial de docentes: aportes para la reflexión y el debate. Bogotá, CO: Pontificia Universidad Javeriana.

Cabra-Torres, F., & Marín, D. L. (2015). Formar para investigar e innovar: tensiones y preguntas sobre la formación inicial de maestros en Colombia [Training for research and innovation: Tensions and questions on initial teacher training in Colombia]. Revista Colombiana de Educación, 68, 149-171. https://doi.org/10.17227/01203916.68rce149.171.

Cárdenas, M. L., González, A., & Álvarez, A. (2010). El desarrollo profesional de los docentes de inglés en ejercicio: algunas consideraciones conceptuales para Colombia [In-service English teachers’ profesional development: Some conceptual considerations for Colombia]. Folios, 31, 49-68. https://doi.org/10.17227/01234870.31folios49.67.

Castro-Gómez, S. (2005). La hybris del punto cero: ciencia, raza e ilustración en la Nueva Granada (1750-1816). Bogotá, CO: Pontificia Universidad Javeriana.

Corona Berkin, S., & Kaltmeier, O. (Eds.). (2012). En diálogo: metodologías horizontales en ciencias sociales y culturales. Barcelona, ES: Gedisa.

De Zubiría, J. (2014, May). ¿Para qué el inglés si todavía ni hablamos español? Semana. Retrieved from http://www.semana.com/educacion/articulo/ley-de-bilingismo-del-ministerio-naiconal-de-educacion/380930-3.

De Zubiría, J. (2016, March). De nada sirve el bilingüismo sin buena educación. Razonpublica.com. Retrieved from http://www.razonpublica.com/index.php/economia-y-sociedad/9311-de-nada-sirve-el-bilingueismo-sin-buena-educacion.html.

Dirección de Investigaciones – ÚNICA. (2016). Estado del arte de los trabajos de grado 2009 – 2016. Bogotá, CO: Institución Universitaria Colombo Americana – ÚNICA.

Dussel, E. (2000). Europa, modernidad y eurocentrismo. En E. Lander (Ed.), La colonialidad del saber: eurocentrismo y ciencias sociales. Perspectivas latinoamericanas (pp. 41-53). Buenos Aires, AR: CLACSO.

Faez, F. (2011). Reconceptualizing the native/nonnative speaker dichotomy. Journal of Language, Identity and Education, 10(4), 231-249. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2011.598127.

Fals-Borda, O. y Rodríguez-Brandão, C. (1987). Investigación participativa (2ª ed.). Montevideo, UY: Ediciones de la Banda Oriental.

Foucault, M. (2002). La arqueología del saber. Buenos Aires, AR: Siglo XXI.

Giroux, H. (2012, October). The disappearance of public intellectuals. Counterpunch. Retrieved from http://www.counterpunch.org/2012/10/08/the-disappearance-of-public-intellectuals/.

González, A. (2007). Professional development of EFL teachers in Colombia: Between colonial and local practices. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 12(1), 309-332.

González, A. (2009). On alternative and additional certifications in English language teaching: The case of Colombian EFL teachers’ professional development. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 14(22), 183-209.

González, A. (2010). English and English teaching in Colombia. Tensions and possibilities in the expanding circle. In A. Kirkpatrick (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of world Englishes (pp. 332-352). Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

González, A. (2012). On English language teaching and teacher education: Academic disagreements in a developing country. Paper presented at the 2nd International Conference: The Future of Education. Retrieved from http://conference.pixel-online.net/edu_future2012/common/download/Paper_pdf/524-SE76-FP-Gonzalez-FOE2012.pdf.

González, A., Montoya, C., & Sierra, N. (2002). What do EFL teachers seek in professional development programs? Voices from teachers. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 7(1), 29-50.

González, A., & Sierra, N. (2005). The professional development of foreign language teacher educators: Another challenge for professional communities. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 10(1), 11-39.

Grosfoguel, R. (2006). La descolonización de la economía política y los estudios postcoloniales: transmodernidad, pensamiento fronterizo y colonialidad global. Tabula Rasa, 4, 17-48. https://doi.org/10.25058/20112742.245.

Kachru, B. B. (1990). World Englishes and applied linguistics. World Englishes, 9(1), 3-20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-971X.1990.tb00683.x.

Kaltmeier, O. (2012). Hacia la descolonización de las metodologías: reciprocidad, horizontalidad y poder. En S. Corona & O. Kaltmeier (Eds.), En diálogo: metodologías horizontales en ciencias sociales y culturales (pp. 25-54). Barcelona, ES: Gedisa.

Kemmis, S., & McTaggart, R. (1988). The action research reader. Victoria, AU: Deakin University Press.

Kincheloe, J. L. (2004). The knowledges of teacher education: Developing a critical complex epistemology. Teacher Education Quarterly, 31(1), 49-66.

Kincheloe, J. L., & McLaren, P. (2005). Rethinking critical theory and qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 303-342). Thousand Oaks, US: Sage Publications.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2016). The decolonial option in English teaching: Can the subaltern act? TESOL Quarterly, 50(1), 66-85. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.202.

Lander, E. (Ed.) (2000). La colonialidad del saber: eurocentrismo y ciencias sociales. Perspectivas latinoamericanas. Buenos Aires, AR: CLACSO.

Lukes, S. (1985). El poder: un enfoque radical. Madrid, ES: Siglo XXI.

Madison, D. S. (2012). Critical ethnography: Method, ethics and performance. Thousand Oaks, US: Sage Publications.

Maturana, L. M. (2011). La enseñanza del inglés en tiempos del Plan Nacional de Bilingüismo en algunas instituciones públicas: factores lingüísticos y pedagógicos [Teaching English in times of the National Bilingual Program in some State schools: Linguistic and pedagogical factors]. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 13(2), 74-87. https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.3770.

McIntyre, C. (2000). The art of action research in the classroom. London, UK: David Fulton Publishers.

Medgyes, P. (1992). Native or non-native: who’s worth more? ELT Journal, 46(4), 340-349. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/46.4.340.

Mignolo, W. D. (2000). La colonialidad a lo largo y a lo ancho: el hemisferio occidental en el horizonte colonial de la modernidad. En E. Lander (Ed.), La colonialidad del saber: eurocentrismo y ciencias sociales. Perspectivas latinoamericanas (pp. 57-85). Buenos Aires, AR: CLACSO.

Mignolo, W. D. (2001). Introducción. En W. D. Mignolo (Ed.), Capitalismo y geopolítica del conocimiento: el eurocentrismo y la filosofía de la liberación en el debate intelectual contemporáneo (pp. 9-54). Buenos Aires, AR: Ediciones del Signo y Duke University.

Mignolo, W. D. (2003). Historias locales/diseños globales: colonialidad, conocimientos subalternos y pensamiento fronterizo. Madrid, ES: Ediciones Akal.

Mignolo, W. D. (2005). The idea of Latin America. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing.

Mignolo, W. D. (2007a). Delinking: The rhetoric of modernity, the logic of coloniality and the grammar of de-coloniality. Cultural Studies, 21(2), 449-514. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601162647.

Mignolo, W. D. (2007b). La idea de América Latina: la herida colonial y la opción decolonial. Barcelona, ES: Gedisa.

Mills, G. E. (2007). Action research: A guide for the teacher researcher. New Jersey, US: Pearson.

Moussu, L., & Llurda, E. (2008). Non-native English-speaking English language teachers: History and research. Language Teaching, 41(3), 315-348. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444808005028.

Phipps, A., & Levine, G. (2012). What is language pedagogy for? In G. Levine & A. Phipps. (Eds.), AAUSC issues in language program direction 2010: Critical and intercultural theory and language pedagogy (pp. 1-14). Boston, US: Heinle Cengage Learning.

Portera, A. (2011). Intercultural and multicultural education: Epistemological and semantic aspects. In C. A. Grant & A. Portera (Eds.), Intercultural and multicultural education: Enhancing global interconnectedness (pp. 12-30). New York, US: Routledge.

Quijano, A. (1992). Colonialidad y modernidad-racionalidad. En H. Bonilla (Ed.), Los conquistados: 1492 y la población indígena de las Américas (pp. 437-447). Bogotá, CO: Tercer Mundo Editores.

Rampton, M. B. H. (1990). Displacing the “native speaker”: Expertise, affiliation, and inheritance. ELT Journal, 44(2), 97-101. https://doi.org/10.1093/eltj/44.2.97.

Restrepo, E., & Rojas, A. (2010). Inflexión decolonial: fuentes, conceptos y cuestionamientos. Popayán, CO: Universidad del Cauca, Instituto de Estudios Sociales y Culturales Pensar y Universidad Javeriana.

Sagor, R. (2000). Guiding school improvement with action research. Alexandria, US: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Viáfara, J. J. (2016). I’m missing something”: (Non)nativeness in prospective teachers as Spanish and English speakers. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 18(2), 11-24. https://doi.org/10.14483/calj.v18n2.9477.

Wallace, M. J. (1998). Action research for language teachers. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Walsh. C. (2005). Interculturalidad, conocimientos y decolonialidad [Inter-culturality, knowledge, and decoloniality]. Signo y Pensamiento, 24(46), 39-50.

Walsh, C. (2009). Interculturalidad crítica y pedagogía de-colonial: apuestas (des)de el in-surgir, re-existir y re-vivir. En V. M. Candau (Ed.). Educação intercultural na América Latina: entre concepções, tensões e propostas (pp. 14-53). Rio de Janeiro, BR: 7 letras.

Carlo Granados-Beltrán holds an MA in British cultural studies and ELT from the University of Warwick (UK) and an MA in applied linguistics from Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas (Colombia). He is currently pursuing his PhD in education at Universidad Santo Tomás (Colombia). He is a professor of the BA program in bilingual education at ÚNICA University.