https://doi.org/10.19183/how.25.1.358

Edgar Luceroa

Jeesica Scalante-Moralesb

aUniversidad de La Salle, Bogotá, Colombia. E-mail: elucero@unisalle.edu.co

bUniversidad de La Salle, Bogotá, Colombia. E-mail: jscalante35@unisalle.edu.co

Received: March 28, 2017. Accepted: August 29, 2017.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Lucero, E., & Scalante-Morales, J. (2018). English language teacher educator interactional styles: Heterogeneity and homogeneity in the ELTE classroom. HOW, 25(1), 11-31. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.25.1.358.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. License Deed can be consulted at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This article presents a research study on the interactional styles of teacher educators in the English language teacher education classroom. Two research methodologies, ethnomethodological conversation analysis and self-evaluation of teacher talk were applied to analyze 34 content- and language-based classes of nine English language teacher educators of three undergraduate English language teacher education programs in Bogotá, Colombia. Findings show that English language teacher educators’ interactional styles are a mixture of both individual (heterogeneous interactional styles) and common (homogeneous interactional styles) social acts, which are represented by the interactional forms and patterns that these teacher educators display in the classrooms.

Key words: Classroom interaction, English language teacher education, interactional styles.

Este artículo presenta un estudio sobre los estilos de interacción de los docentes educadores de profesores en las clases de licenciatura en la enseñanza del inglés. Dos metodologías de investigación se usaron, análisis de conversación etnometodológica y auto-evaluación del modo de hablar del profesor, con las cuales se analizaron 34 clases de contenido y lengua de nueve docentes educadores en tres programas de pregrado de licenciaturas en la enseñanza del inglés en Bogotá, Colombia. Los resultados muestran que los estilos de interacción de los docentes educadores son concebidos como la combinación de actos sociales y comportamientos individuales (estilos interaccionales heterogéneos) y comunes (estilos interaccionales homogéneos) que son representados por las formas y los patrones de interacción que los docentes educadores realizan en el salón de clase.

Palabras clave: educación de profesores de lengua inglesa, estilos interaccionales, interacción en el aula.

This article presents a complementary set of results of a research study on classroom interaction in English language teacher education (ELTE) programs (Lucero & Rouse, 2017). The study focuses on identifying the way teacher educators interact with their students (pre-service teachers) in classes of English language teaching and corresponding disciplinary and pedagogical content knowledge. While analyzing the interactions, we discovered that the nine teacher educators participating in the study appeared to display a degree of homogeneity and heterogeneity in the way they were interacting with their students. Then, the focus of the study was broadened from only analyzing the interaction patterns in ELTE classroom interaction to studying teacher educators’ interactional styles in those patterns as well.

Inside ELTE classrooms, varied expressions, socio-linguistic styles, and interaction patterns have an incidence in the way interaction happens. For English language teacher educators, identifying how they interact in English with their students in the classroom may be a relevant issue in their teaching practices, which can allow them to understand the way classroom interaction happens for the purpose of teaching English language and disciplinary content. The insights in this article pursue this goal. The article presents a complementary set of results of a study on English language teacher educators’ interactional styles in which we offer evidence of a sense of homogeneity and heterogeneity in these styles.

The occurring interaction in this context may vary depending on classroom circumstances such as conversation topics, class activities, students’ affective factors, or participants’ conversational agendas (Lucero & Rouse, 2017; Seedhouse, 2004). That interaction occurs within an ongoing performance inside the classroom with both teacher educators and students asking for and giving responses, interjecting, overlapping, interrupting, and doing other multiple forms of interaction sequences. We would like to clarify that the focus of this article is not on participants’ use of language under a linguistic perspective, but on a social-interactional view in which “grammar and lexical choices [are] sets of resources which participants deploy, monitor, interpret and manipulate” (Schegloff, Koshik, Jacoby, & Olsher, 2002, p. 15). Therefore, this article will not provide a taxonomy of teacher educators’ interactional styles, but a viewpoint to understand how those styles are realized throughout classroom interaction in ELTE settings.

The first concept to understand is classroom interaction in the field of English language education. Ellis (1994) explains that classroom interaction in this field is a set of communicative events, which are conversations or exchanges. These events are co-constructed by teachers and learners to form a context with the objective of promoting language learning and use. Subsequently, Johnson (1995) makes clear as regards the purpose of interaction inside the classroom: to engage learners in conversation, to shape language, and to promote not only language learning but also language use. Both authors manifest that classroom interaction has two main aims: promoting language learning and fostering language use. Complementarily, Lucero (2015) formulates that classroom interaction also serves to acquire knowledge about the language and the world. This author highlights the importance of being aware of the management of classroom interaction.

According to Seedhouse (2004), Walsh (2011), and Lucero (2015), awareness of interactional forms is one of the means by which language teaching and learning can be revealed. Those forms are noticeable in interaction patterns that portray the repetitive sequences of turns in the interaction between two speakers in a context (Cazden, 1986, 1988; Sinclair & Coulthard, 1975). Once interaction patterns are set, they can inform about turns of speaking, participants’ conversational agendas, and understandings of what is happening in terms of interaction inside the language classroom. Different from other social settings, the language classroom is the place where one talks about knowledge to an audience, usually for evaluative purposes (Tracy & Robles, 2013).

Interaction patterns in English language teaching have been studied mostly in classrooms of adult students and where English is the primary spoken language all around. These studies have mainly focused on the adjacency or minimal pairs that language teachers’ types of questions create (Cameron, 2001; Garton, 2002; Huth, 2006; Long & Sato, 1983; Markee, 1995), the pedagogical implications of the initiation-response-evaluation/feedback (IRF/E) sequence (Cazden, 1988; Ellis, 1994; Sinclair & Coulthard, 1975), and the uses of repair (Schegloff, 1997, 2000) and recast (Ellis & Sheen, 2006; Lyster, 1998) for language accuracy.

Nonetheless, the study of the interactional styles that these interactional patterns may create has experienced only slight interest. Schegloff (1997, 2000) and Seedhouse (2004) have implied a review of style in interaction in the structure and organization of it. Their call signals or reveals the fact that the structure of classroom interaction can serve to understand how its participants achieve conversational and communicative goals within styles of interaction. This understanding can give a primary idea to reviewing interactional styles in ELTE classrooms, which are part of the way in which teacher educators interact with their students to promote not only language learning and use but also content, disciplinary, and pedagogical knowledge about language teaching and the world.

Classroom interaction is connected to teaching styles. Bennet (1976) defines teaching styles as “the teacher’s pervasive personal behavior and media used during interaction with learners” (p. 27). Heimlich and Norland (1994) connect teaching styles to language teachers’ personal behavior in language instruction, while Grasha (1994, 2002) alludes not only to the behavior of language teachers in the classroom but also to their personal qualities. For this author, a teaching style is the way in which language teachers guide and direct instructional processes; any teaching style “has an effect on students and their ability to learn” (Grasha, 1994, p. 144).

There are two common elements in the abovementioned conceptualizations: Teaching styles are connected to teachers’ instructional behavior as they have an impact on English language teaching and learning (Scovel, 2001). Bennet (1976) mentions interaction as the way prevalent personal behavior is used, while Grasha (1994, 2002) categorizes teaching styles in regard to instructional processes. Specifically, finding understandings about teaching styles in classroom interaction is not very usual, although the conceptualizations imply that classroom interaction is key to constructing an understanding of a teaching style.

In sum, we see that classroom interaction refers to the way in which English language teacher educators interact with their students to promote learning about language and the world. Subsequently, we see that teaching styles refers to English language teacher educators’ behavior in language or content instruction, which is connected to their teaching beliefs, didactics, and personal qualities. From the merger of these two understandings, we construct the conceptualization of teacher educator interactional styles. These refer to the mixture of both individual and common behaviors in English language instruction and use, which are represented by the repertoire of interactional forms associated with the type of classroom interactant1 the teacher educator is in the classroom.

The individual behaviors in English language instruction and use are all those interactional practices that are characteristic of each teacher educator during the co-construction of interaction with students in classroom activities for the purpose of English teaching, learning, practice, and use. Conversely, common behaviors in English language instruction and use are all those interactional practices that most teacher educators co-construct with students during class activities for interactional purposes. The repertoire of interactional forms are, for example, expressions, socio-linguistic styles, and discursive levels (such as language used and linguistic components) emergent in the interactions between teacher educators and their students in class activities.2 Interactional styles differ from conversational styles in one way: While the latter focus on how to enact politeness, expressiveness, and directness, the former refer to how the linguistic features of turns and interaction are constructed (Tracy & Robles, 2013).

Teacher educator interactional styles may project a sense of homogeneity and heterogeneity. We understand homogeneity as the common social acts in teaching practices during classroom interaction and heterogeneity as those social acts in teaching practices that belong to each teacher educator’s interactional style and are not common in all classroom interactions. Teacher educator interactional styles are not scripted features of how to interact in the ELTE classroom since teacher educators permanently co-construct their interactional styles with students, turn-by-turn. From this co-constructed context, they both create a whole environment for language teaching, learning, and use in the classroom. All this occurs through interaction with the purpose of achieving their conversational agendas inside the ELTE classroom (see Lucero & Rouse, 2017, for more elaboration on this issue).

To identify the interactional forms, their characteristics and pedagogical implications progressively with the aim of revealing the teacher educators’ interactional styles, we repeated the two research approaches implemented in Lucero and Rouse’s (2017) study: The ethnomethodological conversation analysis (ECA) and the self-evaluation of teacher talk (SETT).

The ECA (Seedhouse, 2004) served to identify and describe the interaction patterns and forms. We video-recorded 34 sessions of nine teacher educators teaching content-based and language-based courses at different English proficiency levels of three ELTE undergraduate programs (usually between the A2 and B2 levels according to the Common European Framework of Reference, CEFR). Two of the programs occurred in private universities and the other in a state university. The teacher educators all have an English language C1 proficiency level certified, and hold at least a Master Degree either in applied linguistics, education, or English language teaching. They are also experienced teacher educators with 6 to 16 years of teaching related courses at university level.

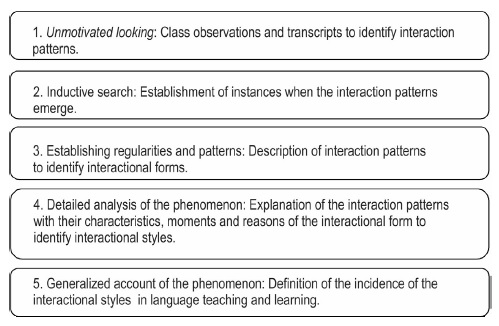

After recording, we transcribed the classroom interaction and created a matrix of analysis with the instances in which regular interaction patterns and forms occurred. With this compendium of instances, we were able to explain the prominent characteristics and moments of emergence of each form and pattern with a vision of interactional styles. We followed the steps in Figure 1 to identify them.

Figure 1. Stages of Ethnomethodological Conversation Analysis (Seedhouse, 2004)

After analyzing the classroom interaction in each of the 34recorded sessions and each matrix containing the identified interaction patterns, we studied the exchanges before and after each pattern to explain the situational moment and reasons of emergence of the interactional forms, which helped us to determine the interactional styles. We interviewed each of the nine teacher educators to understand, on the one hand, the way they organized either language or content teaching and learning; and on the other hand, the interaction around the materials used and the lesson activities. We then created a second matrix of analysis containing the insights gathered in each interview. Following the SETT methodology (Walsh, 2011), we organized these insights into four modes as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. SETT Modes (Walsh, 2011) That Belong to the Matrix of Analysis, Post-Interview

The two matrices were put together, regularity-to-regularity contrasted with mode-to-mode. This comparison aims to analyze the relationship among the interaction patterns, the emergent interactional forms, and the teacher educators’ interactional styles.

The contrast between the findings from both approaches served to identify the social acts in the teacher educators’ teaching practices during the interactions with their students in the classrooms observed. This manner for the teacher educators to manage content and English in the ELTE classroom interaction helped in turn to identify their interactional styles. In the matrices of analysis, we were able to identify that almost all teacher educators followed similar interactional styles, though some of them maintained their own. A degree of homogeneity and heterogeneity in the way in which they interact with their students was then determined. These two degrees of interactional styles displayed teaching behaviors and interaction patterns together by providing an accounting of their divergent factors (class activities, conversational agendas, and interaction context), which influenced and modified the type of interaction that took place between teacher educators and their students. Once teacher educators were able to realize the manner in which they were interacting with their students, they reached a major level of cognizance and understanding of what usually happened inside the classroom in terms of interaction. This knowledge may lead teacher educators to further reflections about their teaching practices.

Teacher Educator Interactional Styles in ELTE Classroom

In the analysis conducted, teacher educators’ styles are seen from an interactional point of view. The focus is thus not on studying the realization of teaching methods or approaches in ELTE classroom interaction but rather on the interactional forms of discourse that teacher educators create with their students in this setting. Several conversational and interactional factors and tensions keep pulling and shaping classroom interaction in ELTE. As a result, this modifies teacher educators’ interactional styles. Verbal interactional exchange is the focus in these findings. In agreement with Cazden (2001), “spoken language is the medium by which teaching takes place, and in which students demonstrate to teachers much of what they have learned” (p. 16).

Thus, the realization of English language teaching methods, approaches, and methodologies do not define teacher educators’ interactional styles, as it might be understood in Richards and Rodgers (2014), Larsen-Freeman (2002), and Ur (2013). The way in which interaction is established and managed by participants (teacher educators and their students) in a social context (the classroom) gives an ampler understanding of these interactional styles (Bucholtz & Hall, 2005). As ELTE classroom interaction may present different tensions in the exchange of ideas and knowledge, teacher educators feel the need to react as a consequence of those tensions. That reaction reveals their interactional styles.

Considering teacher educators to be the first model that pre-service teachers see when learning a new language and its disciplinary and pedagogical knowledge (as Richards and Rodgers (2014) and Larsen-Freeman (2002) suggest through their understanding of methodologies shaping classroom interaction), one can see that the way in which interaction in the language classroom (ELTE classroom in this case) occurs becomes key in understanding teacher educators’ interactional styles. Language and disciplinary contents, as well as students’ motivation or efficacy are influenced by their teacher educators’ instructional practices (see more elaboration on this statement in den Brok, Levy, Brekelmans, & Wubbels, 2005; and in Pianta, 1999). From the abovementioned premises, we state that ELTE classroom interaction is the model that pre-service teachers learn to apply from their teacher educators. Inside the ELTE classrooms observed for this study, the teacher educators were seen as the authority; students tended to look for the best reply-turn to the type of explanations, requests, and contributions that the teacher educators presented throughout class activities. In the next example, in a content-based class of a BA program, this situation was represented.

Excerpt 13

(After giving directions for several minutes)

01. TE: We are going to be permanently speaking all the time because English is beautiful! Yes or No?

02. SS: Yes.

03. TE: Yeahhh. And it is very easy. Yes or No?

04. SS: Yes.

05. TE: Yes, yes. It’s really easy. You know what the thing is? Time of exposure to the language. Yeah?

06. SS: Yes.

The teacher educator asked the same question, “yes or no?” to her students in two opportunities. They eventually answered “yes”. After this, the teacher educator reinforced their positive answer. When the third sequence of this pattern of question-response-affirmation occurred (Turn 05), the teacher educator did not need to repeat the same phrase “yes or no?” Only a word, “yeah?” was enough to receive the same positive answer from the students.

In an after interview with this teacher educator, she was asked about this “yes or no?” question. She manifested that it was common in her classes, but that it did not happen in order to receive a specific answer. She realized that she did this “unconsciously”, but that her students had already discovered and followed this pattern: Even if they did not agree with it or with the content asked, they knew she was expecting a positive answer, which they gave without vacillation. This example then evidences the way students accommodate themselves to the best responses to the type of interaction that teacher educators present throughout classes, which in turn can be reproduced in their own classes when doing their pedagogical practicum.

The teacher educators observed for this study commonly used this type of questions in their classes (asking just to receive students’ affirmative responses). This interactional practice is a representation of the socio-linguistic style that they use in an interactional form: Adding “yes or no?” at the end of a question is mostly used as a tag which is meant to ask about students’ personal feelings or thoughts on the topic of the interaction, although a positive answer is always expected. Another example is the teacher educators’ question of “do you know what X is...?” This type of question is also a representation of the socio-linguistic style that they use in an interactional form: A type of question that requests students’ knowledge, although they do not have it yet or do not need to have it.

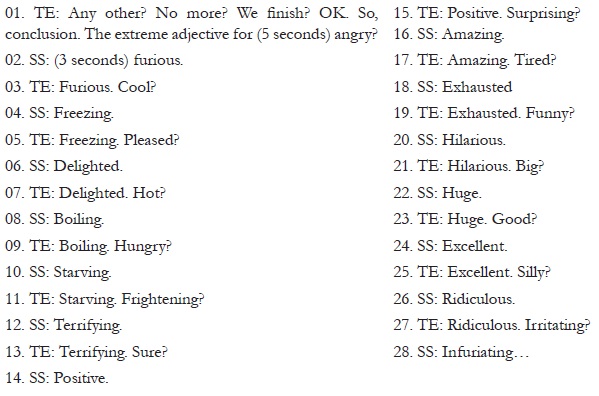

As Excerpt 1 demonstrates, the interactional forms that teacher educators display during classroom interaction, such as socio-linguistic styles, represent their interactional styles. Next, in Excerpt 2, a long pattern exercised by another teacher educator and her students during a language-based class also gives evidence of the way teacher educators establish their interactional styles in ELTE classroom interaction. In this example, the students were practicing a list of adjectives in English.

Excerpt 2

In this example, the way students interactively followed their teacher educator without doubting how the interaction went is evident. Here, students took three seconds to understand what the teacher educator was trying to do and they repeated the same interaction pattern until the end of the event. This pattern is called Initiation-Response-Repetition (IRR) (Castiblanco, 2016): Teacher educator initiates the pattern with a language form to be practiced, students answer with the language form requested, the teacher educator repeats the students’ answer and re-initiates the pattern with another language form. The students in this case kept giving the response that the teacher educator expected until the moment when only she finished the interaction. In the analysis, we observed that students neither finished this type of interaction nor questioned why their teacher educators used it. In all the language-based classes recorded, this IRR interaction pattern is repeated on several occasions, some longer than others. It seems to be that this interaction pattern is the result of an assumed manner of interacting in English language classes for practicing language forms.

One of the main objectives of English language teachers is to guide students to achieve a higher degree of communicative competence (Johnson, 1995; Larsen-Freeman, 2002; Richards & Rodgers, 2014; Van Lier, 1988). With this in mind, ELTE has “relied heavily on the value of interaction—of live, person-to-person encounters” (Allwright, 1984, p. 156). Allwright asserts that that interaction should be “inherent in the very notion of classroom pedagogy itself,” and “successful pedagogy, in any subject, must involve the management of classroom interaction” (pp. 158-159). These premises clearly explain the importance of classroom interaction in relation to language and content learning in ELTE. That importance becomes real when teacher educators are aware of their interaction patterns and interactional forms in the classroom. Although some interaction patterns can be catalogued as common in the teaching profession (Lucero, 2015), every teacher educator should consider them in order to identify their interactional style. Equally, interactional forms such as the use of body language, fixed expressions, linguistic styles, and adaptation to perceived discursive levels should be part of that analysis. In the data collected for the research study presented in this article, we correspondingly noticed the existence of a degree of difference and similarity in the types of interaction that each observed teacher educator used/uses with their students. Those similarities and differences in the way they interact with the students are also part of their interactional styles, distinguished as homogeneous and heterogeneous interactional styles. For the continuation of the findings, we now account for these two types of interactional styles.

Teacher Educators’ Homogeneous Interactional Styles

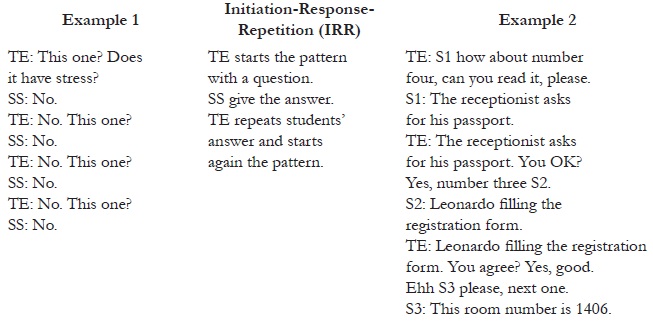

Homogeneity is established when similar social acts happen in teacher educators’ interactional styles during class activities. The social acts, which always have the purpose of providing students with spaces to learn and use English and disciplinary contents, reveal the repertoire of interactional forms that teacher educators follow during class activities. Although there are differences in the type of students belonging to a class, as well as in the purposes of students and teacher educators’ conversational agendas and class activities, teacher educators enact similar interactional styles by performing similar interactional structures and purposes. The students progressively get the ability to understand, respond, and follow those structures and purposes even without being aware that they do it. That is to say, homogeneous interactional styles are teacher educators’ interactional practices with students in which the same interaction patterns, expressions, and socio-linguistic styles are used, yet in different class activities. In Excerpt 3, we show two interactions that happened in two different classes and with two different teacher educators. Despite this, the interactional style is the same.

Excerpt 3

In both examples, the teacher educator started the interaction by asking students a question; after this, the students gave the answer to that question and finally, the teacher educator repeats that given answer and starts the pattern again. As shown in Excerpt 3, this interactional style took place the same in both cases. This gives evidence of homogeneity in the interactional style of both teacher educators yet in different classes. The class of Example 1 was at the languages laboratory working on English intonation and stress (a content-based class); due to its arrangement, in sections of four computers per table, the teacher educator mostly had a more individual interaction, face to face with the students. In the second case, a language-based class, the teacher educator was standing and nominating students to answer exercises from the book in the classroom.

One’s first thought may indicate that different classes with different participants should create different interaction patterns since the type of classroom and occurring interaction may equally be different, but it is not what happened in our observations. In Excerpt 3, both scenarios were different but the interactional patterns happening inside both classes were developed in the same way. The interactional style displayed by both teacher educators did not change, proving a level of homogeneity in the way in which teacher educators interacted with their students, although class scenarios varied. Excerpt 4 corroborates this finding.

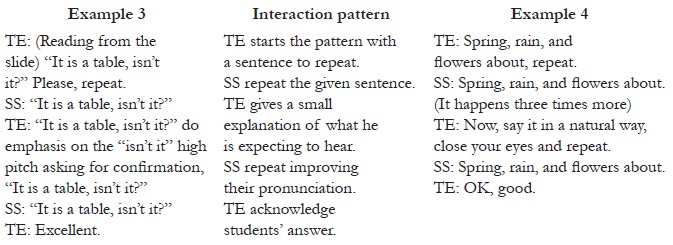

Excerpt 4

Both interactions emerged in two different classrooms with two different teacher educators. Example 3 was displayed in a content-based class of phonetics; here, the teacher educator was teaching stress in pronunciation. He used sentences that his students had to repeat until they got the right intonation. Considering that this class activity was about pronunciation, one might expect to find this kind of interaction pattern: the teacher educator having the students repeat the intonation of the same sentence several times until they got it correctly.

Now, Example 4 occurred in a language-based class (first difference from Example 3). The teacher educator’s purpose for the class activity was not specifically an emphasis on pronunciation but communication (second difference). These students had to produce coherent answers to the teacher educator’s requests, and the space to correct them was not immediately after their utterance (third difference). Nevertheless, the teacher educator displayed a similar interactional style to the one in Example 3, whose main purpose was teaching phonetics. Both interactions are alike, as both teacher educators picked the students’ responses and had them repeat them again until they did it correctly. Both teacher educators kept on encouraging the students to repeat the response, explained what was expected to hear, and stopped the interaction when they were satisfied with the students’ outcome.

To summarize, homogeneous interactional styles take place when two or more teacher educators enact the same interaction patterns with students despite other influencing factors. Homogeneity is co-constructed when divergent tensions are set, but teacher educators’ interactional style stays the same, represented by the immutability of the structure of the interaction. We then highlight the fact that degrees of similarities and differences are involved in ELTE classroom interaction. In the following part, we are going to account for the differences in teacher educators’ interactional styles.

Teacher Educators’ Heterogeneous Interactional Styles

It is said that students who belong to language classrooms should experience a difference in the process of teaching and learning (Álvarez, 2008; Cameron 2001; Ellis, 1994; Markee, 1995; Van Lier, 1988). This difference is accounted for in terms of methods and approaches (Brown, 2007; Oxford et al., 1998; Richards & Rodgers, 2014) but we argue it also happens in line with interactional practices, which the teacher roles seem to establish in each method or approach. In our point of view, teacher educators are not replicas and students are not simply imitators of interactional manners; thus, interactional practices do not always follow expected manners. This is when heterogeneous interactional styles emerge.

Heterogeneous interactional styles are those different sets of social acts that occur in similar interactional scenarios in the ELTE classroom. Equal to teacher educators’ homogeneous interactional style, the social acts in teacher educators’ heterogeneous style also have the purpose of providing students with spaces to learn and use English and disciplinary contents, revealing the repertoire of interactional forms that teacher educators use during class activities. In the previous part, we said that similar social acts are present in different scenarios. Here, heterogeneity is the opposite: Different social acts are occurring in similar scenarios.

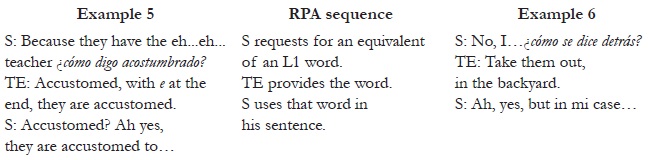

Excerpt 5 illustrates two events in which heterogeneity in the teacher educators’ interactional styles is evident. Again, two situations are compared; both were language-based classes with a communicative purpose. In both cases, the students were on the task of explaining their ideas but they had a complication because they seemed to have forgotten a word that completed their idea. They then had to interrupt their own responses to ask their teacher educator for the forgotten word. Both students in Examples 5 and 6 used the strategy of backing up their breakdown with the use of their first language (Spanish).

Excerpt 5

After the students had asked for the L2 equivalent, differences in the way in which the teacher educators answered were evident. The one in Example 5 provided the L2 equivalent and added a small explanation of spelling. This teacher educator also reinitiated the students’ sentence. The one in Example 6, on the other hand, not only provided the L2 equivalent but also gave it grammatically correct and contained into the whole sentence the student was trying to build. The way these two teacher educators responded to the Request-Provision-Acknowledgment (RPA) pattern (Lucero, 2011) can influence the way students answer to it, and the structure of the interaction itself. As soon as the students received the L2 equivalent, both seemed to recognize it. This is evident when both acknowledged it by saying “Ah, yes”. However, the structure of the RPA sequence was evidently altered. The student in Example 5 included the provided L2 equivalent in his sentence and kept on expressing his idea. Conversely, the student in Example 6 just acknowledged the provided L2 equivalent but did not use it in his sentence; he created a new sentence and did not use the given L2 equivalent as the structure of this RPA sequence propounds. This situation complements Lucero’s (2011) RPA sequence by showing that not only the way teacher (educators) respond to the students’ request of the L2 equivalent constructs the sequence, but also, such construction is modified by the way in which the students acknowledge the provision. In terms of teacher educators’ heterogeneous interactional styles, it is noticeable how both examples had the purpose of providing students with spaces to learn and use English during class activities; however, differences in providing the L2 equivalent and acknowledging it was evident in these two similar scenarios.

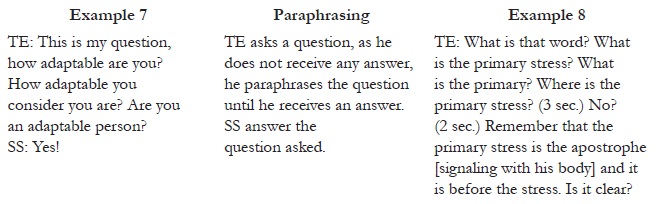

Excerpt 6 also demonstrates heterogeneity in teacher educators’ interactional styles in the ELTE classroom. Not only their answers can modify interaction but also their questions can do it during class activities.

Excerpt 6

Examples 7 and 8 above reflect heterogeneity in teacher educators’ interactional style. The structure of the adjacency pair of question and response is incomplete by the students’ no-answer. The two examples happened in two different content-based classes. The teacher educators started the interaction by asking about content of the class activity (Lucero, 2012), and consequently, expecting an answer from the students. Only the teacher educator in Example 7 received an answer. The other in Example 8 did not, although he paraphrased the question four times. As this happened, this teacher educator modified the structure of the interaction by self-responding to the question. A deeper analysis of this example revealed that both questions might possibly contain uncommon L2 words for the students (“adaptable” and “stress”).

Although the students responded in Example 7, the answer did not seem to be coherent with the original question. They only responded with the monosyllable “yes”. This might be the result of the paraphrasing of the original question to a yes/no question. On the other hand, in Example 8, the teacher educator maintained the paraphrasing under the wh-question structure, but he did not receive an answer. He then had to give an answer-explanation to keep the class activity going.

This is how heterogeneity in teacher educators’ interactional styles works in ELTE classroom interaction. Every situation of the current classroom interaction is considered, but the result may vary. Two classes with similar activities, purposes, and events can produce differences in the way teacher educators and students display interaction patterns and forms.

Interactional patterns and interactional forms shape ELTE classroom interaction. Both in turn constitute teacher educators’ interactional styles. In line with Bucholtz and Hall (2005), we believe that those linguistic and interactional forms that any individual selects and uses during their interactions with others create interactional styles. Under this premise, individuals cannot construct their interactional styles by themselves. The presence of at least a second person with his or her own selection of linguistic and interactional forms is necessary. When the two individuals interact in a situated context, their interactional styles for that context emerge. By transporting these foundations to ELTE classroom interaction, we have been able to provide the basic standards to understand homogeneity and heterogeneity in teacher educators’ interactional styles.

Due to the levels of dynamism and variety regarding the time and place of the emergence of teacher educators’ interactional styles, it is not possible to categorize them. Actually, a taxonomy of these styles may contribute to the labeling of teacher educators, an issue that loads them with descriptions that can be unfair and go against diversity. Furthermore, interaction is composed of a huge collection of linguistic forms, which do not happen in the same way in similar interactional contexts, less in varied scenarios. A speaker can use linguistic forms in such an infinite manner that categorizing them will be an endless endeavor. In consonance with Bell (1984) and Coupland (1980), we agree that those linguistic forms are related to the type of person an individual is. Both scholars attach the linguistic forms to linguistic styles. When put into context and realized during interaction, interactional styles can be identified.

In ELTE classroom interaction, these principles happen too. The teacher educators observed use a multiplicity of linguistic and interactional forms in interaction with their students in varied class activities and in their emergent situations. Nonetheless, one fact is certain, teacher educators’ interactional styles occur in ELTE classroom interaction, and in the most general level, they have degrees of homogeneity and heterogeneity, as demonstrated throughout this article. Teacher educators tend to talk in similar ways, mostly because of like classroom activities, teaching practices, and interactional styles that they exercise for the ELTE classroom, regardless the contents of the class. Eventually, teacher educators also tend to talk differently due to the way the interaction is co-constructed with the students in those classroom activities. A move towards an ampler variety of classroom activities and teaching practices as well as diverse manners of interacting may change teacher educators’ interactional styles and the established mechanics of classroom interaction.

One question remains: How important are teacher educators’ interactional styles in ELTE? Our answer is composed of three reasons. The first is seeing that teacher educators and their students do not seem to be aware of the type of classroom interaction that they create, co-construct, and maintain during class activities. Johnson (1995), Seedhouse (2004), Gibbons (2006), Kurhila (2006), and Lucero (2015) have discussed this issue. This unawareness leads them to create, construct, and maintain routinized interactional practices. As interaction is the main means by which language teaching and learning occur (Cazden, 2001; Lucero, 2015; Walsh, 2011), teacher educators should learn how they interact with their students in the classroom for the purpose of learning English and its pedagogical content. Knowledge shared in this article about teacher educators’ interactional styles may help raise certain level of this awareness.

The second reason is in terms of English language teaching. The more teacher educators understand how ELTE classroom interaction happens, the more they can take advantage of it to improve the teaching of English and its pedagogical content. Teacher educators need to do more than teach language and its contents by mechanized interactional practices. They need to understand the situational and interactional factors functioning or in motion during classes to reflect upon and improve their own teaching and interactional practices.

The third reason deals with breaking the tendency to look outside for the teaching strategies or methodologies that solve classroom inner situations. This article does not tell teacher educators what interactional style they should subscribe to. Instead, it sets the foundation to invite each one, even pre-service teachers, to rethink themselves as classroom-interactants in the classroom. Of course, these items/elements—awareness, understanding, and reflection—take time; ongoing analysis of one’s every class is necessary. This is why our persistence in identifying how teacher educators interact in ELTE is key to understanding teaching and learning practices, although many factors, for instance interactional styles and the context, may influence classroom practices (Young, 2008). Teacher educators cannot fall into the trap of normalizing ELTE classroom interaction as if everyone needed to interact in the same way with students. We suggest not forgetting that teacher educators are teaching future language teachers; the interactional practices exercised in the ELTE classroom are the ones they usually learn and may be the ones that they will likely put into practice in their English language classrooms. An unconscious and routinized type of classroom interaction distances itself more and more from the dynamics of everyday talk in other social contexts, the contexts where English learners will mostly need to use the language. Recognizing interactional styles as a starting point of change is then a challenge that requires teacher educators to hone their ability to observe and reflect upon their own teaching practices.

Teacher educators’ interactional styles are a mixture of individual and common behavior represented by interactional forms (expressions, socio-linguistic styles, and discursive levels) and interactional patterns. Both teacher educators and students (pre-service teachers), through the utterances that they both produce in ELTE classroom interaction, elaborate this notion of interactional styles. A major finding of the research study presented in this article is that teacher educator interactional styles can be homogenous or heterogeneous; homogeneous when teacher educators produce similar social acts in different scenarios, and heterogeneous in the other way around. Both interactional styles are evidences of how malleable ELTE classroom interaction is. Two different classes can hold either similar or different activities, purposes, and events, which in turn may all produce similar or different interactional practices.

In this article, insights show that talking about ELTE classroom interaction refers not only to the structure of the utterances shared between teacher educators and pre-service teachers. ELTE classroom interaction is also the fabric to understand the way its participants create, co-construct, and maintain interactional practices for negotiating meaning and sharing knowledge. It is a matter of awareness how every teacher educator uses these different shapes to achieve their conversational agendas and get a better understanding of how classroom interaction happens.

1This concept of interactant has been coined from the use that some authors have given to it: an individual who interacts in conversational exchanges (Antaki & Widdicombe, 1998; Bucholtz & Hall, 2005; Hua, Seedhouse, Wei, & Cook, 2007; Tracy & Robles, 2013). According to Cashman (2005), being an interactant implies being competent to interact with others in a determined context. Interactant is defined in Antaki’s (2011) theory of interaction as the person who acts in the “shared mental world”, that world is “shared and maintained in and through sequentially organized turns”; interactant’s expectations and understandings of their co-interactant’s behavior, intentions, and motives converge in that world (pp. 238-239).

2Interaction patterns, interactional forms, and interactional styles are interconnected. The sequences in interaction and their characteristics (interaction patterns) can contain other aspects as expressions, socio-linguistic styles, and discursive levels (interactional forms). It is through these interactional forms that interactional styles can be unveiled.

3In the excerpts, “TE” means teacher educator, “S” means a student. “S1”, “S2”, and so on, are the number of students participating in the excerpt. “SS” indicates a turn produced in unison by most of the students.

Allwright, D. (1984). Observation in the language classroom. New York, US: Longman.

Álvarez, J. A. (2008). Instructional sequences of English language teachers: An attempt to describe them. HOW, 15(1), 29-48.

Antaki, A. (Ed.). (2011). Applied conversation analysis: Intervention and change in institutional talk. London, UK: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230316874.

Antaki, C., & Widdicombe, S. (Eds.) (1998). Identities in talk. London, UK: Sage Publications.

Bell, A. (1984). Language style as audience design. Language in Society, 13(2), 145-204. https://doi.org/10.1017/S004740450001037X.

Bennet, N. (1976). Teaching styles and pupil progress. Cambridge, US: Harvard University Press.

Brown, H. D. (2007). Teaching by principles: An interactive approach to language pedagogy (3rd ed.). New York, US: Pearson Longman.

Bucholtz, M., & Hall, K. (2005). Identity and interaction: a sociocultural linguistic approach. Discourse Studies, 7(4-5), 585-614. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445605054407.

Cameron, D. (2001). Working with spoken discourse. London, UK: Sage Publications.

Cashman, H. R. (2005). Identities at play: Language preference and group membership in bilingual talk in interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 37(3), 301-315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2004.10.004.

Castiblanco, S. (2016). Interactional architecture in TEFL classes (Unpublished undergraduate monograph). Universidad de La Salle, Bogotá, Colombia.

Cazden, C. (1986). Classroom discourse. In M. C. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (3rd ed., pp. 432-463). New York, US: MacMillan.

Cazden, C. B. (1988). Classroom discourse: The language of teaching and learning (1st ed.). Portsmouth, US: Heinemann.

Cazden, C. B. (2001). Classroom discourse: The language of teaching and learning (2nd ed.). Portsmouth, US: Heinemann.

Coupland, N. (1980). Style-shifting in a Cardiff work-setting. Language in Society, 9(1), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404500007752.

den Brok, P., Levy, J., Brekelmans, M., & Wubbels, T. (2005). The effect of teacher interpersonal behavior on students’ subject-specific motivation. Journal of Classroom Interaction, 40(2), 20-33.

Ellis, R. (1994). The study of second language acquisition. New York, US: Oxford University Press.

Ellis, R., & Sheen, Y. (2006). Reexamining the role of recast in second language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 28(4), 575-600. https://doi.org/10.1017/S027226310606027X.

Garton, S. (2002). Learner initiative in the language classroom. ELT Journal, 56(1), 47-56. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/56.1.47.

Gibbons, P. (2006). Bridging discourses in the ESL classroom: Students, teachers and researchers. London, UK: Continuum Editorial.

Grasha, A. F. (1994). A matter of style: The teacher as expert, formal authority, personal model, facilitator, and delegator. College Teaching, 42(4), 142-149. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.1994.9926845.

Grasha. A. F. (2002). The dynamics of one-on-one teaching. College Teaching, 50(4), 139-146. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567550209595895.

Heimlich, J. E., & Norland, E. (1994). Developing teaching style in adult education. San Francisco, US: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Hua, Z., Seedhouse, P., Wei, L., & Cook, V. (Eds.) (2007). Language learning and teaching in social inter-action. London, UK: Palgrave MacMillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230591240.

Huth, T. (2006). Negotiating structure and culture: L2 learners’ realization of L2 compliment-response sequences in talk-in-interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 38(12), 2025-2050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2006.04.010.

Johnson, K. E. (1995). Understanding communication in second language classrooms. New York, US: Cambridge University Press.

Kurhila, S. (2006). Second language interaction. Amsterdam, NL: John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/pbns.145.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2002). Techniques and principles in language teaching. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Long, H. M., & Sato, C. (1983). Classroom foreigner talk discourse: Forms and functions of teachers’ questions. In H. W. Seliger & M. H. Long (Eds.), Classroom oriented research in second language acquisition (pp. 268-286). Cambridge, UK: Newbury House Publishers.

Lucero, E. (2011). Code switching to know a TL equivalent of an L1 word: Request-provision-acknowledgement (RPA) sequence. HOW, 18(1), 58-72.

Lucero, E. (2012). Asking about content and adding content: Two patterns of classroom interaction. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 14(1), 28-44. https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.3811.

Lucero, E. (2015). Doing research on classroom interaction: Approaches, studies, and reasons. In W. Escobar & H. Castañeda-Peña (Eds.), Studies in discourse analysis in the Colombian context (pp. 83-113). Bogota, CO: Editorial El Bosque.

Lucero, E., & Rouse, M. E. (2017). Classroom interaction in ELTE undergraduate programs: Characteristics and pedagogical implications. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 19(1), 193-208.https://doi.org/10.14483/22487085.10801.

Lyster, R. (1998). Recasts, repetition, and ambiguity in L2 classroom discourse. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 20, 51-81.

Markee, N. P. (1995). Teachers’ answers to students’ questions: Problematizing the issue of making meaning. Issues in Applied Linguistics, 6(2), 63-92.

Oxford, R., Tomlinson, S., Barcelos, A., Harrington, C., Lavine, R. Z., Saleh, A., & Longhini, A. (1998). Clashing metaphors about classroom teachers: Toward a systematic typology for language teaching field. System, 26(1), 3-50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(97)00071-7.

Pianta, R. C. (1999). Enhancing relationships: Between children and teachers. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10314-000.

Richards, J. C., & Rodgers, T. S. (2014). Approaches and methods in language teaching (3rd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Schegloff, E. A. (1997). Third turn repair. In G. R. Guy, C. Feagin, D. Schiffrin, & J. Baugh (Eds.), Towards a social science of language: Social interaction and discourse structures (Vol. 2, pp. 31-40). Amsterdam, NL: John Benjamins Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1075/cilt.128.05sch.

Schegloff, E. A. (2000). When others initiate repair. Applied Linguistics, 21(2), 205-243. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/21.2.205.

Schegloff, E. A., Koshik, I., Jacoby, S., & Olsher, D. (2002). Conversation analysis and applied linguistics. American Review of Applied Linguistics, 22, 3-31. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190502000016.

Scovel, T. (2001). Learning new languages: A guide to second language acquisition. New York, US: Cengage Learning.

Seedhouse, P. (2004). The interactional architecture of the second language classroom: A conversational analysis perspective. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Sinclair, J. M., & Coulthard, R. M. (1975). Towards an analysis of discourse: The English used by teachers and pupils. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Tracy, K., & Robles, J. S. (2013). Everyday talk: Building and reflecting identities (2nd ed.). New York, US: The Guilford Press.

Ur, P. (2013). A course in English language teaching (3rd ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Van Lier, L. (1988). The classroom and the language learner. New York, US: Longman.

Walsh, S. (2011). Exploring classroom discourse: Language in action. New York, US: Routledge.

Young, R. (2008). Language and interaction: An advanced resource book. New York, US: Routledge.

Edgar Lucero is a full-time teacher in the BA program in Spanish, English, and French of Universidad de La Salle, Bogotá, Colombia. He works in the curricular areas of didactics, research, and pedagogical practicum. He is currently doing his doctoral studies in education, ELT emphasis, at Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas, Colombia.

Jeesica Scalante-Morales is an in-service teacher graduated from the BA program in Spanish, English, and French of Universidad de La Salle, Bogotá, Colombia. She teaches English language for adults and children. Her research interests are in-classroom interaction and its connection with English teaching didactics.