https://doi.org/10.19183/how.25.1.362

Sandra Milena Ramírez Ortiza

Marco Tulio Artunduaga Cuéllarb

aEscuela Misael Pastrana Borrero, La Plata, Colombia. E-mail: 1979smro@gmail.com

bUniversidad Surcolombiana, Neiva, Colombia. E-mail: marcot.artunduaga@usco.edu.co

Received: April 1, 2017. Accepted: August 22, 2017.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Ramírez Ortiz, S. M., & Artunduaga Cuéllar, M. T. (2018). Authentic tasks to foster oral production among English as a foreign language learners. HOW, 25(1), 51-68. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.25.1.362.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. License Deed can be consulted at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Attaining oral production is a challenge for most English language teachers because most of the strategies implemented in class do not engage students in speaking activities. Tasks are an optimal alternative to engage learners in communicative exchanges. This article presents the results of a qualitative action research study examining the effects of authentic tasks in oral production with a group of tenth graders in a public high school in the south of Colombia. Considering the conclusions of the study teachers are encouraged to use authentic tasks in the classroom to involve students in meaningful learning to foster oral production.

Key words: Authentic tasks, English as a foreign language learners, meaningful learning, oral production.

Desarrollar la producción oral es un desafío para la mayoría de los profesores de inglés ya que muchas de las estrategias empleadas en clase no involucran a los estudiantes en actividades de habla. Las tareas son una alternativa óptima para involucrar a los estudiantes en intercambios comunicativos. Este artículo presenta los resultados de un estudio cualitativo de investigación acción que explora los efectos del uso de tareas auténticas en la producción oral en un grupo de estudiantes de décimo grado en una institución pública del sur de Colombia. Las conclusiones del estudio invitan a los profesores a utilizar tareas auténticas en el aula para involucrar a los estudiantes en un aprendizaje significativo y así fomentar la producción oral.

Palabras clave: aprendizaje significativo, estudiantes de inglés como lengua extranjera, producción oral, tareas auténticas.

Teaching English in contexts where it is not seen as a priority and where opportunities to practice the language are limited makes the school the only place where communicative practices can be generated. One of the challenges in those settings is to involve students in meaningful speaking activities so that they can use the language actively. Students’ low level of vocabulary and pronunciation are determinant factors that prevent them from speaking English. Additionally, the natural anxiety and fear many learners experience using the language orally also play their role in the situation (Ansari, 2015; Soto-Santiago, Rivera, & Mazak, 2015; Tsiplakides 2009).

Fink (2003) highlights the importance of inspiring students to connect the knowledge received in classes with their lives so that this information can be used in new situations. Frequently, students are reluctant to take part in oral activities because they do not see any relevance between these topics or activities and their daily lives; as a consequence, the main purpose of the research study was to explore the impact of authentic tasks in the oral production of English as a foreign language (EFL) learners. Not only did this action research project aim at involving students actively in what Nunan (1989) suggests regarding tasks, but also in the selection of contents and information, the preparation and presentation of topics and tasks, and a reflection on the process.

Given the importance of engaging students in active learning, authentic tasks were thought of as an effective alternative to bring students’ reality to the classroom to foster oral production. That is why the research question that the study searched to answer was: What impact do authentic tasks have in fostering oral production in a group of EFL learners?

Regarding oral production and the teaching of speaking, Goh and Burns (2012) recognize that “speaking is a highly complex and dynamic skill that involves the use of several simultaneous processes—cognitive, physical and socio-cultural—and a speaker’s knowledge and skills have to be activated rapidly in real time” (p. 166). This claim calls for the involvement of students in meaningful situations where they can use the language to understand and interpret their reality, construct new knowledge, and develop their communicative competences at the same time.

Hedge (2002) claims that the most important element concerning spoken competence is to identify the different types of situations in which the language is produced. Afterwards, students can communicate their own ideas, opinions, beliefs, or preferences for which they need to be equipped with some background knowledge, expressions, and vocabulary. The social function of the language is a crucial aspect to be considered as well. That is why teachers are required to conceptualize the speaking activities to involve students in using English for real and meaningful purposes so that their communicative competences are developed. The complexity of the spoken competence is also emphasized by Chastain (1998) who recognizes that “speaking is a productive skill which involves many components and goes beyond making the right sounds, choosing the right words, or getting the constructions grammatically correct” (p. 330).

Among the reasons students have to avoid taking part in oral activities are their natural fear and anxiety to speak a foreign language as emphasized by Tsiplakides (2009), Soto-Santiago et al. (2015), and Ansari (2015). According to Horwitz, Horwitz, and Cope (1986) foreign language anxiety is due to “a distinct complex construct of self-perceptions, beliefs, feelings, and behaviours related to classroom language learning arising from the uniqueness of language learning process” (p. 128). These authors highlight three components of anxiety: (a) communication apprehension, (b) test anxiety, and (c) fear of negative evaluation. Some other reasons that prevent students from using the language orally are the lack of vocabulary and/or knowledge of rules about how that language works and the fear of errors.

EFL teachers are faced with the challenge of planning appropriate speaking activities that foster oral production bearing in mind the reality of errors and students’ reactions to them as a risk factor for any communicative effort. Hedge (2002) concludes that it is important to construct self-confidence in the students by using meaningful activities to create a positive atmosphere in the classroom and proposes pair work to develop fluency. Teachers are called upon to generate better learning conditions in which all students become active participants working on teams, helping and collaborating with each other to attain respect and understanding. In this regard, Eyring (2002) claims that “teachers wishing to humanize the classroom experience treat students as individuals, patiently encourage self-expression, seriously listen to learner response, provide opportunities for learning by doing, and make learning meaningful to students in the here and now” (p. 334).

Considering the problematic situation identified in the diagnosis phase of the research study, we decided to focus on the “spoken production” as a constituent element of communicative competence given the fact that according to the Colombian Ministry of Education (Ministerio de Educación Nacional, 2006), that should be the main goal in English language teaching (ELT). More specifically, the productive skills corresponding to the monologue section for the students’ level were taken into account for the tasks. In order to achieve the desired outcomes of the study, creating an appealing atmosphere in the classroom was essential to ensure an active participation in speaking activities.

Willis (1996) claims that one way to create an engaging setting is by using the language with meaningful purposes and that is the main reason why tasks were used. Tasks provide a useful alternative to engage students in a meaningful context where the main objective is to make the language learning process a more natural one. Willis declares that a task is “an activity where the target language is used by the learner for a communicative purpose (goal) in order to achieve an outcome” (p. 23). Skehan (as cited in Richards & Renandya, 2002), proposes that “a task is an activity in which meaning is primary, there is a communication problem to solve, and the task is closely related to real-world activities” (p. 97). In this statement we found the rationale to use authentic tasks.

Another important element in ELT is the authenticity factor. Nunan (1989) claims that “authentic refers to any material which has not been specifically produced for the purpose of language teaching” (p. 54). Later, Nunan (1991) goes beyond the authenticity of materials and proposes different ways of characterizing activities within a communicative framework and within the criterion of authenticity:

The activities can be either real-world or pedagogic. Real-world tasks are tasks that a regular person would do in a real-world context. Pedagogic tasks are recreated in the classroom to serve as exercises for practicing and for using the language. (p. 25)

An authentic task, therefore, might be considered as such as long as it has a clear and direct relationship with the things that happen in daily life. Guariento and Morley (2001) remark that task authenticity depends on four aspects: a genuine purpose, real world purpose, classroom interaction, and learners’ engagement. Additionally, these authors state that “to integrate input and output, reception and production, is to mirror real world communicative processes, and is something that all teachers concerned with moving towards authenticity should aim to do” (p. 352).

Willis (1996) proposes a task-based lesson with three stages:

This research study followed the action research parameters, considering that it was based on classroom research carried out by the teacher-researcher to reflect, analyze, improve, and evaluate a particular issue found in the local context. Burns (2003) defines action research as a form of self-reflective inquiry conducted by participants in a social situation. For these purposes, critical reflection about our teaching practices and the learning process is required.

The action research model proposed by Kemmis and McTaggart (1985): “Planning, action, observation and reflection” (p. 11) was followed in the study. Planning implies the identification of a problematic situation in our communities. Action requires analyzing the problematic situation; in this case, lack of participation in speaking activities in order to design and implement the proposal. Observation provides important insights about the development of the strategy, and the use of video recordings and transcripts of the lessons observed helped to identify strengths and weaknesses in the implementation of the planned tasks. Furthermore, in the reflection stage the students’ and teachers’ perceptions about the implementation of the study were considered.

Participants

The participants in the study comprised eight students from tenth level who had been studying in the school for more than three years. These students were selected for convenience in terms of schedule and availability. The participants in the study shared similar conditions in terms of socio economic stratum, age, and special interests in music, technology, and sports. Most participants were basic users of English (A1) which was determined through a diagnosis test called “Retos al Saber”.1 According to the descriptors of the Common European Framework (Council of Europe, 2001) these learners could “interact in a simple way, repeat or paraphrase at a lower rate of speech, still their spoken interaction and production was limited” (p. 24).

Since the student-participants were underage, it was necessary to ask all of them as well as their parents to sign a consent letter indicating their acceptance to participate in the study.

The syllabus for the English courses in the high school focuses on reading and writing in order to prepare students for Pruebas Saber 11.2 As a consequence, oral skills receive little attention. For that reason, this study wanted to encourage students to enhance their oral production and to make the learning process more meaningful through the use of tasks.

Instruments and Data Collection Procedures

Sharkey and Clavijo-Olarte (2012) argue that “community-based pedagogies are curriculum and practices that reflect knowledge and appreciation of the communities in which schools are located and students and their families inhabit” (p. 131). Therefore, in order to collect first-hand information from the members of the school community different instruments were used. During the preliminary stage of the project, some techniques such as empirical observation, community visit, Likert scale, literature map, and students’ voices were used to determine a point of departure.

Creswell (2009) claims that “a qualitative observation is when the researcher takes field notes on the behavior and activities of individuals at the research site” (p. 239). In that sense, by sharing with the participants in their setting, the teacher-researcher could know more about the problematic situation and that is how through empirical observations, the teacher could identify some concerns in students’ work when there were speaking activities in the classroom.

The next source of information was a survey used to inquire into students’ opinions about the problematic situation. Additionally, and to complement what they manifested in the survey, some students were asked to expand on their answers. A literature map3 and a Likert scale4 were also used to determine the problematic aspect, namely the lack of students’ participation in speaking activities. According to Creswell (2009), a literature map is “a visual picture (or figure) of groupings of the literature on the topic that illustrates how your particular study will contribute to the literature, positioning your study within the larger body of research” (p. 64).

During the implementation of the tasks, information came from direct observation and the analysis of the tasks and the students’ attitudes, performances, and reflections. Data were collected from different sources and through different instruments such as video recordings, interviews, and field notes. Hopkins (2008) claims that field notes are “a way of reporting observations, reflections and reactions to classroom problems” (p. 103); for this reason, field notes were used to register opinions and impressions about the pedagogical intervention and describe processes students were engaged in while the task was implemented. Similarly, the pedagogical interventions were video recorded to observe students’ performance and attitudes. Later, the video recordings of the students’ oral presentations were transcribed to analyze oral skills features. Finally, an interview was applied at the end of each task to the eight participants to know about their experiences and perceptions of the tasks. These three instruments were used during each implementation session.

The themes for each implementation session were selected based on the results of a survey applied at the beginning of the study and designed to determine the common topics students were interested in. The selected topics were: sports, organizing a farewell party for 11th graders, music, and embarrassing moments. Four different authentic tasks whose individual implementation took approximately three class sessions were designed for the pedagogical intervention.

The tasks followed Willis’ (1996) model (Pre-task, task cycle, and language focus). In the pre-task phase the teacher explored the topic with the class, highlighted useful words and phrases, and provided students with examples. In the task cycle part, students worked in the task in pairs or small groups and prepared the report. In the language focus stage opportunities for students to analyze and practice specific linguistic forms were provided.

The procedure for the implementation of each task required first that the topic of the task was negotiated with the students taking into account their interests and likes. Next, the material for the class was selected or designed. Finally, the instrument to collect information about the tasks was designed and the oral performance of the 35 students was recorded. It is important to clarify that the implementation of each task took up to two weeks to complete due to extra factors such as changes in the schedule and administrative meetings, among others. Pair work, group work, and individual work were used to encourage students to use the language.

When planning the tasks, students were asked about their previous experiences with English. The results showed that the students were aware of the importance of speaking and they wanted to improve. Most of the students also manifested that most of the time they understood what the teacher said in the L2 but had difficulties responding or interacting in English. Additionally, they manifested that those difficulties were due to lack of vocabulary, a poor level of pronunciation, and fear of speaking in front of others, because they fear being evaluated by teachers and peers, and they also experience a lack of interest in the speaking activities due to uninteresting topics. The previous data confirmed that students needed to work with significant tasks (related to their interests) but also authentic ones (reflecting what they do in real life) to foster their communicative competence.

As previously stated, four tasks were designed and implemented during the study. The first task about a sporting event was selected because it was one of the students’ favorite topics. Moreover, tenth graders were the organizers of the school soccer championship. For the development of the task, students worked in pairs so that they had the opportunity to exchange information about their favorite sports considering elements such as equipment needed, place to practice it, conditions, and rules, among others. Additionally, a tablet was given to each pair so they watched a video about some sporting events. During the development of these activities, anxiety yet also enthusiasm were evident in the majority of the students. Spanish was highly used but little by little, as the students lowered their anxiety, new vocabulary and expressions in English were incorporated in their language. The teacher’s main role was to monitor and answer questions. The final goal of the task was to prepare a creative poster about a sporting event and to invite and convince their partners to participate in it. An important condition was that students needed to make use of the vocabulary and expressions previously learnt.

Considering that it is a school tradition that tenth graders organize a farewell party for eleventh graders, the second task was about planning such party. Students needed to work in groups to collect ideas, select the best ones, organize and present their proposals to the rest of the group. Even though this was the second task, some students continued using Spanish during the activity. However, little by little they started using English more because they wanted their ideas to be clear in order that their proposal would be chosen for the “real” party. Students enjoyed the task because it provided them with an opportunity to plan what they would like to do for their 11th grade partners’ party.

As the first and second tasks were done in groups, the next one was done individually. It consisted of an oral presentation about their favorite type of music. Students prepared a PowerPoint presentation in which they had the chance to talk about their favorite singer, their favorite songs, and show their favorite video clip explaining why they liked it. Not only did this task prove to be very interesting because of the topic but also because students were engaged with technology. They were particularly allowed to use their cellphones to show their favorite songs during the presentation to the whole group.

The final task required students to record themselves talking about an embarrassing experience. For this task, the teacher showed students some pictures to introduce certain expressions and vocabulary and then students watched some movie tracks related to embarrassing moments. This was a funny part of the task because participants started to relate what happened in the videos with similar events in their lives. The final product of the task required students to share with their partners a funny or embarrassing story. Most of the students accompanied their presentation with gestures and paralinguistic features.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that one aspect that helped to accomplish the objectives of the study was the fact that during the tasks the students worked cooperatively to support each other.

During the implementation of the tasks, three instruments were used to collect data: field notes, video recordings with their transcripts, and students’ interviews. The software ATLAS.ti which allows the analysis of qualitative data was used.

During the data analysis process, some patterns emerged and were then grouped into categories. The first main category that appeared was related to the effect of using authentic tasks in students’ oral production. This one helped to determine the competences in oral production that are fostered when using tasks, which was the second category. Finally, using authentic tasks inside the classroom provided the opportunity to determine the type of tasks that facilitate oral production which, in turn, constituted the third category.

Effects of Authentic Tasks on Students’ Oral Production

This first category provided information about how the use of authentic tasks has a direct effect on students’ oral production in terms of engaging them in speaking tasks. The tasks designed and the materials used had the purpose of reducing students’ difficulties that affected their oral production. During the implementation, it was seen that little by little students started to increase their participation in the different activities. This was mainly because their needs and interests had been taken into account. Not only were they seen as language users and learners but also as people capable of making their own decisions and whose opinions were important.

The following excerpts, taken from learners’ interviews5 and the teacher-researcher’s field notes, show that the tasks implemented had a positive effect on the students’ oral production.

Extract 1: I can do the tasks as I want to; I do my best to do a nice task and to present a good exposition about my likes. (S2, Interview)

Extract 2: Topics are part of our life so we take advantage of them to learn more things. (S3, Interview)

Extract 3: The class started and the students were eager to attend the class because of the use of cell phones and music. (Teacher’s field notes)

It is worth highlighting that since the beginning of the process, students were encouraged to choose the topics they wanted to talk about. This issue proved to be very positive as evidenced in Extract 1 where one of the things that the student remarked on is that he did his best to present the report because he wanted to talk about his likes in a better way. Additionally, we can see that the student took an active role in the learning process making decisions according to his interests. Extract 2 provided a general insight about the task in which the student remarked on the importance of using topics related to her daily life because that connection facilitated the presentation of the task. Finally, Extract 3 suggests that the use of technological devices, such as cellphones, contributed to an active participation during the task.

At the end of each implementation session, an interview was conducted to ask students to reflect on the tasks, which enabled them to express their opinions, ideas, and perceptions about the whole process. Their opinions showed that students had improved their self-confidence and adopted a different perception towards learning English. This can be seen when analyzing the answers to one of the questions about whether they would like to perform similar tasks, and why. Here are some of the answers:

S2: I paid attention enough to every task because I think that the tasks were according to our level of English, in spite of that we do not speak perfect English, we are making an extra effort to learn it every single day.

S3: The strategy is very good because I can say more words in English.

S4: The task is very interesting; we learn more English and we lose the fear to do oral presentations.

S5: We learn words that we have never said before and in that way we improve our speaking skill.

It can be seen how the implementation of the different tasks involved students in speaking activities and helped them to overcome some difficulties such as fear, inhibition and having nothing to say at the moment of speaking. These students’ statements also evidence that they felt a sense of improvement in their English performance.

One aspect that had a positive effect on oral production was the one related to group work, and one of the most significant findings was that students helped each other while developing the different tasks. The previous aspects contributed to creating a good atmosphere in the classroom which motivated students to participate during the different tasks as evidenced in the following excerpts:

What was interesting in this part was the students’ attitude; they were helping each other while doing the activity. (Teacher’s field notes)

S3: I enjoyed working with my classmates. They helped me a lot. (Interview)

It was also found that students’ participation in oral activities increased as they were actively engaged in the tasks. Along the process, they needed to ask for new information and that is how the need for oral interaction emerged. Students started paying attention to their partners’ oral presentations which in turn helped them to construct and improve their own presentations and, in that way, they felt more comfortable when speaking. It was also possible to observe that the students started making decisions about their learning process.

Competences Developed in Oral Production

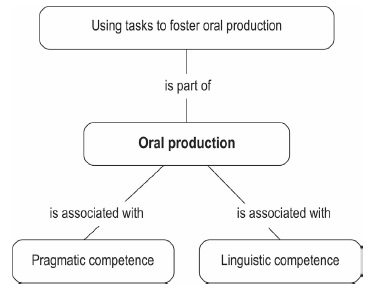

The second category has to do with the competences in oral production that are fostered when using tasks. It was seen that the use of tasks had an evident impact in the development of oral production in terms of linguistic and pragmatic competences as can be seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Competences Developed in Oral Production

At the beginning of the study, students were reluctant to participate in speaking activities but after the implementation of authentic tasks, they became more active participants which was seen when they started using more words orally. The progressive use of new words and phrases was not always done accurately; however, this aspect was not seen as a difficulty because mistakes in terms of usage, grammar, or pronunciation were seen as natural in the process of developing oral production.

Regarding linguistic competence, important findings emerged along the process. First, the use of images was essential for students to be understood. Later, ideas were expressed following a linear sequence of events. In some cases, examples were used to support and elaborate on their ideas. What is more, when some students did not know or could not remember a word, they simply said it in Spanish and continued with their oral report. The following excerpts show some parts of the students’ oral production:

S2: My favorite band is Cultura Profetica... ehh...their singer is Willy Rodriguez...ehh Their...Their...message...the Bob Marley and my favorite singer is Marlon Javier Castro...Él es o sea, He is Dread Mars I...eh... (Oral presentation)

S1: It is a sport where...compete of 2 teams of 5 players each... (Oral presentation)

S4: My favourite song singer is John Alex Castaño...sing ranchera and has 25 years... (Oral presentation)

S6: I have...speak to the rector of the school for the permission...umm ...the party of the eleven students... (Oral presentation)

These excerpts illustrate specific features of the linguistic competences. It can be noticed that there were some difficulties with certain grammatical structures such as the use of the third person singular (sing ranchera) wrong word choice (and has 25 years), omissions of some words (I have...speak) and code switching (Él es o sea, He is). Another common aspect when students were planning what to say was the use of certain sounds as fillers. Those sounds became common indicators that students were taking time to plan their ideas. What is important to consider is that those strategies were not an obstacle at the moment of transmitting the message. At the end of the study, an improvement in oral production was seen as students started to produce more complex sentences related to daily situations and were more willing to participate in speaking activities.

The pragmatic competence is also fostered through tasks. Tasks provide the opportunity for students to organize their ideas and messages in a coherent way, to connect ideas, to present linear sequence of points, to use key words and expressions, and to associate language and images. These features are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Features of the Pragmatic Competence

It is worth highlighting different types of strategies from the part of students to present their opinions in a coherent way as the following excerpts show:

S3: Good morning friends...good morning teacher... I talk of Katty Perry...Katty Perry ehh name real is Katherine Hudson...live in Santa Barbara, California, United States, October 25...ehh better known as Katty Perry...is a singer...ehh...songwriter uhmm...producer and American ambassador... (Oral presentation)

Students start greeting their partners in formal and informal ways. Some of them use mimics. Additionally, while the students were explaining they were showing the pictures related to the topic. (Teacher’s field notes)

S6: We want to have students...a cordial invitation two days soccer tournament...dos...no...two teams... (Oral presentation)

In the first excerpt, S3 organized the information in a coherent way. Despite the fact that there were some pauses, those were not a barrier for understanding the main idea. In addition, students presented their report using socio-linguistic conventions of the language (greetings) and then they presented their report following a linear sequence of ideas.

One important finding was that during the presentations, code switching, gesturing, along with the use of posters and slides proved to be effective strategies to compensate for students’ limitations with the language. The previous is also an indicator of the students’ effort to maintain communication with the rest of the group. Examples of the previous are shown in the following extracts:

She talked about embarrassing moments using mimics and different gestures to make herself understood. (Teacher’s field notes)

S7: After...you say the words eh...grade eleven...uhmm students stay the space...enjoy the music and start the party (the student moves). (Oral production)

S8: One day...me was the house de one friend...me drink water...uhmm...the glass...fall down (she did the action)...I ashamed. (Oral presentation)

S1: For the party...eh...we do cards...for invitation...the guests are students...eleven...the teacher (the student asks: alquilar en English) (someone says book)...book El Hostal...uhmm snacks son candies... (Oral production)

Students were also asked whether they thought the tasks employed helped them with their oral production and to justify their answer. The participants manifested some very positive perceptions towards the implementation of tasks and recognized that they had contributed to the improvement of their oral production. Comments such as “we learn new words”, “I showed that I can talk in English”, “I am able to learn more English”, “you can express your ideas in a better way”, demonstrate that using tasks related to students’ personal lives helps to establish a connection with the topic of the tasks and in that way their participation in speaking activities increases. This is shown in the following excerpts.

Interview about farewell party: “Do you think that the previous tasks help you to improve your oral production? Yes / No. Why?

S1: Yes, they do because we learn new words and we do better performances in English.

S2: Yes, they do because we learn more aspects about the topic and we learn new words.

S3: Yes, they do because we can express our ideas better and we can speak more in English.

Interview about sports:

S4: The topics are part of our daily life, we have a close relation to them for that reason it is easier for us to talk about them.

S5: The tasks helped me to talk more in English.

S6: The tasks helped me to express our ideas and things. We prepared what to do in English and it helped us a lot.

Type of Tasks That Facilitate Oral Production

Regarding the final objective of the study which was about the type of tasks that facilitate oral production, tasks related to sharing personal experiences, talking about their likes and interests, and planning or creating something seem to be the most effective ones. For instance, when participants were asked about what they liked the most about the tasks they mentioned: “wecan make decisions”, “to express our ideas about the farewell party”, “that we could talk about our personal preference in terms of music”, “toknow my classmates’ preferences”, “to work with daily life tasks”, among others.

These answers were very valuable because the participants expressed positive reactions towards the tasks. What is more, the topics, materials, and resources were important factors in the development of those tasks. These elements engaged students and made them an active part of the process. Therefore, their previous knowledge, their personal experiences and opinions were taken into account at the moment of presenting the tasks; in that sense, students found reasons to express and share their ideas.

To sum up, during the implementation of the research study using authentic tasks, it was evidenced that the participants established a connection with the tasks since the topics, objectives, and final product were relevant, meaningful, interesting, and useful to them. Students also increased their participation in speaking activities independently of their pronunciation and vocabulary problems. Students were able to build meaningful and logical messages and share them with their partners.

The main motivation behind this research study was to find out the effect authentic tasks have on a group of EFL learners’ oral production which was examined in terms of the ability of the students to produce the foreign language in real communicative situations. Although many studies have investigated the role of tasks to develop students’ communicative competence, few studies, such as this one, have considered the use of authentic tasks inside the classroom—taking into account students’ likes and interests. Based on the findings one can assure that authentic tasks, related to students’ daily lives, produce a positive effect on the students in terms of engagement and confidence-building. The use of authentic tasks promotes meaningful negotiation with students about what they want to learn. In that sense, by being actively involved in the teaching-learning process, students become committed decision-makers in terms of content as well as careful evaluators of their own performance. They also start becoming more reflective as tasks provide an optimal context for communicative practices where learners are engaged in their own learning and this makes the learning process a meaningful one.

Regarding the general objective of the study, it can be assured that participants are more willing to speak in class as a result of being actively involved and engaged during the implementation of tasks. This happens when students are encouraged and supported by their partners and, little-by-little, gain confidence and start playing a more active role in speaking activities.

One important factor is the one related with reflection. It is important to allow time for reflection when planning the task. As a result, when students are asked to reflect on their performance, they learn to analyze what they have done well and what needs improvement.

Another important aspect this study dealt with is the type of authentic tasks that facilitate oral production. Participants reported that the four speaking tasks let them express and share their ideas freely. Therefore, it is essential to keep constant communication with the students to determine their favorite topics so they are involved and engaged in the whole process.

Using tasks cause the students to feel more confident at the moment of presenting their oral reports. This happens when participants have the possibility to see a model of the outcome and in that way, they know what is expected. This is only possible with continuous practice and permanent support of teachers and peers. In this regard, authors such as O’Malley and Valdes (1996) state that “to prepare students for an oral report, give them guidelines on how long to speak, how to choose the topic and what areas to address on a topic” (p. 87).

By developing authentic tasks, students foster some competences in their oral production. First, there is an enhancement in linguistic competences because students can report information about topics of interest. Although there can be some grammatical mistakes during the oral presentations, it is certainly true that participants produce more coherent sentences using more complex structures. It can be concluded that the use of authentic tasks also helps the students to increase their confidence at the moment of speaking because they do not concentrate too much on linguistic forms but on reaching their objectives.

The second competence that is fostered using authentic tasks is the pragmatic one. Tasks enrich the learning process and encourage students to participate more actively in class to express their ideas and opinions and to do so they need to use different strategies to be understood.

Finally, teachers are encouraged to look for alternatives to support students in their learning process but specially to overcome the difficulties that affect the development of the communicative competence; and tasks indeed provide an optimal context to achieve that goal.

1This exam is currently used in the school to evaluate students’ knowledge of English and other subjects thanks to an agreement between the institution and a publishing house in charge of designing tests based on the National Standards and Pruebas Saber. This agreement also allows the application of mock exams during the school year to prepare students for standardized tests such as Pruebas Saber 11.

2Name of the State test for students who graduate from high schools in Colombia.

3The literature map was used to connect the focused topic with the literature. It is useful for learning, reflecting and evaluating research articles.

4The Likert scale was used to determine how the students felt about English skills and the alternatives to improve them.

5The students’ quotes taken from the interviews and used in this part were originally in Spanish and translated by the authors of this article. Excerpts from the teacher’s journal were originally in English.

Ansari, M. S. (2015). Speaking anxiety in ESL/EFL classrooms: A holistic approach and practical study. International Journal of Education Investigation, 2(4), 38-46.

Burns, A. (2003). Collaborative action research for English language teachers. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Chastain, K. (1998). Developing second language skills: Theory and practice (2nd ed.). Chicago, US: Harcourt Brace Publishers.

Council of Europe. (2001). Common European Framework of References for Languages: Learning, teaching, and assessment. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. Los Angeles, US: Sage.

Eyring, J. L. (2002). Experiential and negotiated language learning. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.), Teaching English as a second or foreign language (3rd ed., pp. 333-344). Boston, US: Heinle & Heinle.

Fink, L. D. (2003). What is significant learning? Retrieved from https://www.wcu.edu/WebFiles/PDFs/facultycenter_SignificantLearning.pdf.

Goh, C. C. M., & Burns, A. (2012). Teaching speaking: A holistic approach. New York, US: Cambridge University Press.

Guariento, W., & Morley, J. (2001). Text and task authenticity in the EFL classroom. ELT Journal, 55(4), 347-353. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/55.4.347.

Hedge, T. (2002). Teaching and learning in the language classroom. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Hopkins, D. (2008). A teacher’s guide to classroom research (4th ed.). Maidenhead, UK: Open University Press.

Horwitz, E. K., Horwitz, M. B., & Cope, J. A. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. The Modern Language Journal, 70(2), 125-132. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1986.tb05256.x.

Kemmis, S., & McTaggart, R. (1985). The action research planner. Victoria, AU: Deakin University Press.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional. (2006). Estándares básicos de competencias en lenguas extranjeras: inglés. Bogotá, CO: Author.

Nunan, D. (1989). Understanding language classrooms: A guide for teacher-initiated action. New Jersey, US: Prentice Hall.

Nunan, D. (1991). Language teaching methodology: A textbook for teachers. New York, US: Prentice Hall.

O’Malley, J. M., & Valdez-Pierce, L. V. (1996). Authentic assessment for English language learners: Practical approaches for teachers. Boston, US: Addison Wesley.

Richards, J. C., & Renandya, W. A. (2002). Methodology in language teaching: An anthology of current practice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667190.

Sharkey, J., & Clavijo-Olarte, A. (2012). Community-based pedagogies: Projects and possibilities in Colombia and the United States. In A. Honigsfeld & A. Cohan (Eds.), Breaking the mold of education for culturally and linguistically diverse students: Innovative and successful practices for the 21st Century (pp. 129-138). Lanham, US: Rowman & Littlefield Education.

Soto-Santiago, S. L., Rivera, R. L., & Mazak, C. M. (2015). Con confianza: The emergence of the zone of proximal development in a university ESL course. HOW, 22(1), 10-25. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.22.1.132.

Tsiplakides, I. (2009). Helping students overcome foreign language speaking anxiety in the English classroom: Theoretical issues and practical recommendations. International Education Studies, 2(4), 39-44. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v2n4p39.

Willis, J. (1996). A framework for task-based learning. Edinburg, UK: Longman.

Sandra Milena Ramírez Ortiz holds a BA in modern languages from Universidad Surcolombiana and an MA in English didactics also from Universidad Surcolombiana. She currently teaches English at Misael Pastrana Borrero public school in La Plata, Huila.

Marco Tulio Artunduaga Cuéllar holds a BA in modern languages from Universidad Surcolombiana and an MA in English didactics from Universidad de Caldas (Colombia). Currently, he is a full-time associate professor in the ELT education program and the coordinator of the Master’s degree program in English didactics at Universidad Surcolombiana.