https://doi.org/10.19183/how.25.1.385

Patricia Kim Jiméneza

aUniversidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia, Tunja, Colombia. E-mail: patricia.jimenez@uptc.edu.co

Received: May 23, 2017. Accepted: September 5, 2017.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Jiménez, P. K. (2018). Exploring students’ perceptions about English learning in a public university. HOW, 25(1), 69-91. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.25.1.385.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. License Deed can be consulted at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This manuscript reports the final findings of an exploratory, descriptive case study that aimed at exploring the perceptions of a group of English as a foreign language students in a public university regarding their English learning and the commitment level through the process. A questionnaire, a survey, and the teacher’s diary were the instruments used to gather data. The results showed the way the participants study and learn English, their most common learning styles and study strategies. Additionally, they revealed some students’ low levels of commitment and autonomy, and some indifference as regards English, too.

Key words: Autonomy, commitment, learning styles, students’ perceptions, study strategies.

Este artículo reporta los hallazgos finales de un estudio de caso, descriptivo y exploratorio que pretendía investigar las percepciones de un grupo de estudiantes de inglés como lengua extranjera en una universidad pública, respecto al aprendizaje del inglés y al nivel de compromiso durante el proceso. Los instrumentos utilizados para recolectar información fueron un cuestionario, una encuesta y el diario del profesor. Los resultados muestran la forma como los participantes estudian y aprenden inglés, sus estilos de aprendizaje y estrategias de estudio más comunes. Adicionalmente, revelaron bajos niveles de compromiso y autonomía de algunos estudiantes y también cierta indiferencia por el inglés.

Palabras clave: autonomía, estilos de aprendizaje, estrategias de estudio, percepción de los estudiantes.

The research began based on a generalized concern of the English teachers at the Language Institute belonging to the Colombian public university where the study took place; it regards the increase of students’ dropout rate and poor academic performance in English. It was very worrying to notice the alarming average of students who failed (70%) and around 50% of students dropped out, on average. The main objective of the study was to find out how undergraduate students could become more effective learners and how they could improve their performance. The study focused on exploring and analyzing their study strategies, strengths, weaknesses, learning styles, and degree of commitment.

Thus, through the descriptions done and the findings reported, the current paper also aims to achieve some changes through critical reflection by both actors, teachers and students, since all participants in teaching-learning processes should become involved in the construction of more significant learning experiences. Furthermore, as highlighted by Jiménez (2015), students’ commitment plays a fundamental role in the transformation of education. Jiménez states that didactic materials and classroom activities are very important when learning a foreign language; however, learners’ attitude is the most crucial.

The change in the way students take up English learning might emerge from the analysis of the collected data, from their own perceptions, and the description of facts. Maybe, through awareness, students may understand the need to fully develop their metacognitive skills in order to activate their self-regulation processes (Flavell, 1979) and have control over their own learning to accomplish more suitable results.

The research question that led the study was: What do the perceptions of a group of English as a foreign language (EFL) students at Instituto Internacional de Idiomas of Universidad Pedagógica y Tecnológica de Colombia (UPTC) reveal about their English learning process in terms of learning styles, study skills, motivation, and commitment?

The theoretical constructs that underpinned the study were learning styles, motivation, autonomy, and study skills, elaborated upon as follows.

Learning Styles

According to Brown (2002), there are different kinds of learners because people are different and have different preferences and styles; consequently, individuals differ in how they learn and what senses and parts of their brain are used in the process. Thus, some learners are visual, some are analytical, and many others are impulsive or spontaneous. Some students use their ear more than their hands or words to learn. Others like to learn through music, through numbers or drawings, or by associating objects and concepts. Some students like reading more than speaking. Others prefer to write, listen, or take risks, while some prefer to think carefully before making important decisions. Moreover, some students feel more comfortable working individually while others love group work. Besides, some students are interested in learning grammar, but others might hate it.

Now, defining what a learning style is, Claxton and Murrell (1987) stated that a learning style is the way in which a person acquires, retains, and saves information; other experts held that it is the method a person uses to learn best, or a set of factors, behaviors, and attitudes facilitating learning for an individual in a given situation (Kang, 1999). Oxford (2003) asserted that “learning styles and strategies are among the main factors that help determine how—and how well—students learn a foreign language” (p. 1).

The most suitable definition for the study was Brown’s (2002) which conceives learning styles as patterns that provide direction for learning and teaching, since learning styles influence how students learn, how teachers teach, and how these two interact.

There are three main types of learning styles defined by physical and sensory preferences according to Brown (2002). These are auditory, when learners use their ears as the main mechanism when learning; visual, when they use their eyes; and kinesthetic or tactile, when they like to use different parts of their body while learning. Most students learn best through the combination of these three styles, but everyone is particular.

Motivation

Motivation, according to Harmer (2007), is essential to success and without motivation learners will almost certainly fail to make the necessary effort. Harmer held that motivation is a type of internal drive that pushes someone to do things in order to achieve something.

In language learning, Richards and Schmidt (2002) asserted that motivation is “the combination of learners’ attitudes, desires, and willingness to expend effort in order to learn a second language . . . motivation is generally considered to be one of the primary causes of success and failure in language learning” (p. 344). Here lies the importance of self-motivation when learning English.

The most outstanding types of motivation are: external and internal (Brown, 2002). When students are being pushed by others to learn, motivation is external. However, if students are learning because they want to learn for their own purposes and reasons, this is internal. Summarizing, self-motivation is internaland motivation from others is external. Harmer (2007) called them extrinsic motivation (which comes from outside or external factors) and intrinsic motivation (which comes from inside); this last is the ideal.

Autonomy

Autonomy, for the study, is the main goal in learning processes, since it implies taking control of learning or self-directing it and wanting to do it. This entails being able to make decisions about the best or most appropriate ways to learn and being actively engaged. Furthermore, autonomy involves effort, commitment, and certain independent behavior on the learner’s part.

To support this, Holec (1981) held that autonomy is the ability to take charge of one’s own learning. This practice involves self-determination and decision making about different aspects of learning, such as determining objectives, monitoring the process, and evaluating performance, among others. Little (1991) viewed autonomy as “a capacity for objectivity, critical reflection, decision making, and independent action” (p. 4).

Therefore, it is necessary to be reflective about one’s own learning, take initiative to explore, find solutions, and evaluate results.

Study Skills

Study skills refer to the abilities, activities, techniques, and approaches that are normally applied to learning, to promote it effectively and autonomously. These skills are vital to learners since they help them to be successful and independent. Some researchers associate them with learning strategies. Thus, according to Griffiths (2013), learning strategies are “activities consciously chosen by learners for the purpose of regulating their own language learning” (p. 36).

Other experts defined study skills as effective use of specific methods for learning. They include regular study, listening to lectures, taking notes, efficient written explanations, participation in lessons, doing homework, and preparation for exams (Crow & Crow, 1948; Dodge, 1994; Lewis & Doorlag, 1999; Smith, 2000; Thomas, 1993). As skills are not independent, these experts suggest using them together to achieve a high-level success.

On the other hand, learning strategies have been classified as cognitive, metacognitive, and social-affective (O’Malley & Chamot, 1990) or cognitive, affective, sociocultural-interactive, and the master category of “meta-strategies,” which includes but is not limited to metacognitive strategies (Oxford, 2011). Study skills and learning strategies must always be planned to make learning more effective and meaningful.

The research followed a qualitative approach and focused on interpreting and understanding a problematic situation: the increase of students’ dropout level and the poor academic performance in English. It also attempted to describe their attitudes, autonomy, and commitment manifested and achieved throughout the course. The type of research was an exploratory and descriptive case study whose purpose was to describe and analyze the participants’ perceptions of their own English learning process, and targeted at discovering everything related to the participants’ study method and learning strategies. In addition, it was a case study, because the population consisted of only a sample of population, a small group of participants from the whole population of students in the public university UPTC; that is, a sample of participants who were studying their last level of EFL. The study described events and real situations that occurred in a natural setting, the university campus, and focused on a single social unit (Merriam, 1988).

Participants

Initially, the population consisted of a group of 22 undergraduate students who were in different academic programs and whose ages ranged from 17 to 28 years old. The group was made up of 11 women and 11 men who studied different university programs. These students had to take the Saber Pro Test1 at the end of their programs as a graduation requirement. At the end of the study, only 13 participants—ten women and three men—remained in the process and finished the course as the actual participants whose data were analyzed.

Procedures

Firstly, to be able to develop the study, it was necessary to request the corresponding permissions of the directors and the selected population through a written consent form. Secondly, the instruments used to collect data were a general questionnaire (Appendix 1), a survey (Appendix 2), and the teacher’s diary. All instruments were presented in Spanish to avoid missing pieces of relevant information and were applied one by one during the process that lasted four months. The first instrument used was the questionnaire; it was applied during Week 3 of the first month. Here, it is important to mention that the questionnaires of the students who quit were not taken into account for the study and were discarded. The responses from this first instrument allowed the improvement and redirection of the second instrument, the survey, which was conducted in a sequential and systematic way in the second month. The survey provided key and crucial information to answer the research question, since it contained more specific questions.

When the course started, the teacher’s diary began to be filled in and the important insights and events were coded and colored in order to be triangulated and categorized; I was looking not only for similarities, but also for differences among the supplied information regarding the participants’ learning styles, motivation, autonomy, study skills and strategies. Furthermore, to protect the participants’ identity, they were assigned numbers.

Data Analysis

The information collected through the three instruments was analyzed following the steps from grounded theory method (Corbin & Strauss, 1990). The data were categorized according to the common and repetitive patterns found by using a code system and colors, which allowed me to group, compare, and contrast data and assign names to the most important aspects related to the objectives of the study. Subsequently, the information was triangulated and after establishing concepts, some tentative categories emerged. Every finding during the research process was considered provisional, later refined and classified. Lastly, after a more careful and deeper analysis, those initial categories were redefined and summarized to determine the findings and draw the conclusions.

After analyzing the data and bearing in mind the theoretical constructs, I determined the following to be the findings, which are related to the objective of the study and give response to the research question. The following discoveries describe the participants’ learning styles, motivation, commitment and attitudes, the autonomy they accomplished, and the learning strategies used.

Learning Styles and Learning Strategies

The study found different types of learners among the population who took part in the study. The participants showed their preferences about the way they learned and processed the information during the process.

Taking into account Browns’ (2002) model, I found visual, analytical, auditory, and impulsive learners. The learning styles were evidenced by means of the answers given in the questionnaire and the survey, where students expressed their preferences and the ways they learned best. Also, these were corroborated throughout the course and through the entries made in the teacher’s diary. Some of those styles were also verified by means of participants’ performance on the exams they took during the term. For instance, on those exams, when relating language skills with learning styles, it was found that many of the participants were visual learners. They showed better performance in the exercises with graphical vocabulary, matching, and drawings on tests. Thus, it was easier for them to understand what they saw and read than what they heard. Therefore, listening and grammar were the hardest linguistic skills for many of them, since they did not understand several words and grammatical details, nor reach outstanding scores on tests.

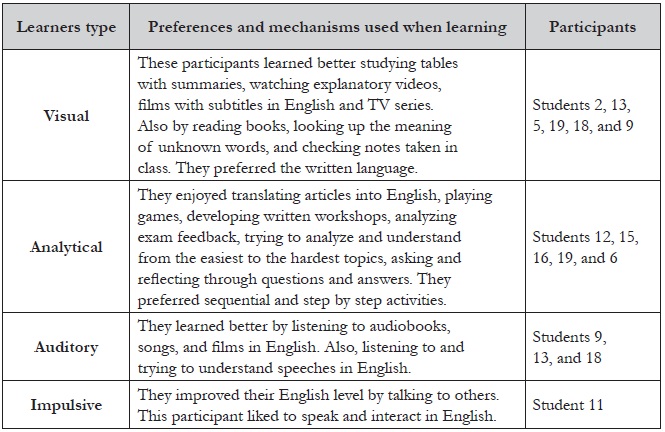

Table 1 summarizes the types of learners found and their preferences (extracted from the three instruments).

Table 1. Types of Learners and Their Learning Preferences

Among the participants, there were six visual learners, five analytical, three auditory, and one impulsive; three participants used to combine styles. These participants’ dominant learning styles evidence they liked to use their eyes to read, their hands to write, their ears to enjoy, and their minds to reflect and analyze.

The six visual participants stated having learned best through readings, by writing, and by taking notes. They also reported to like watching films and videos with subtitles. During classes, they liked it most when the teacher wrote on the board or they could have material in their hands to look at since they felt more confident and comfortable that way. They themselves mentioned having a visual memory.

The analytical participants (5 of the 13) stated they learned best by analyzing, inferring, comparing, reflecting, and reviewing their notes. These skills were more predominant than others for them, so they preferred to analyze things to retain them better. This style was also evidenced through lessons when some of them showed to be critical and aware of their own weaknesses as English learners: “If I studied, I would achieve a better average”2 (Student 15). Moreover, three other participants expressed dissatisfaction with their average grades of previous English levels; they believed they could have improved their score in a substantial way and were conscious of this:

I know I can improve. (Student 15)

I don’t feel satisfied with my accumulated average. I consider I can improve and learn. (Student 19)

I’m not satisfied with my average since I know I can give more of me. (Student 16)

This means that these analytical learners were conscious as regards thinking about the advantages and disadvantages of their dominant styles and reflecting on the skills they needed to strengthen their performance or learning.

To complement what has been mentioned about the analytical learning style, it is relevant to state that according to their own perceptions, 6 of the 13 participants revealed through the questionnaire the lack of study, interest, and effort as the main factors affecting negatively their English performance. This confirms again the use of the analytical style by these participants and also shows honesty, sincerity, and self-reflection. Additionally, these reflective learners were aware of and brave to state that the lack of commitment, autonomy, and real involvement in the learning process was their weakness. Furthermore, one participant was conscious enough to recognize that nonattendance of classes had influenced negatively his academic achievement. Regarding this issue, giving response to question number 4 of the questionnaire concerning the most effective study technique and learning strategies, this participant wrote the following: “It really works taking all the necessary material to class and taking advantage of the class time at maximum” (Student 12). This student used the analytical style not only to learn English, but to reflect on class situations, too.

Closing the discussion about the analytical style, from the options in the survey seven participants selected this choice: “I never go to tutorials although I’m aware that they could be very useful.” In their responses, they showed self-awareness about their own faults and were conscious of their weaknesses. Indeed, their style was reflective and their attitude, too. Student 19 was also aware of having shown little interest and commitment for the subject; in his response to Question 10 related to other learning strategies to make learning more effective, the student stated, “I need to be more committed to study and devote the necessary time to this subject.” This participant was also self-reflective.

Concerning the auditory learning style, the study found three auditory participants. They did very well on tests and used their listening skill to enhance learning the foreign language. Besides, they enjoyed listening to songs when there were listening in workshops during lessons; furthermore, they stated in the questionnaire they used to reinforce this skill by listening to different audio material in English, and enjoying songs and films. Moreover, when evaluating the course contents, listening comprehension was these participants’ strength.

My strategy is listening to English songs. (Student 18)

Techniques such as listening to series in English without subtitles in YouTube have worked for me. Also, applications as Duolingo to reinforce my knowledge. (Student 13)

It works for me to watch movies and listen to songs in English, above all for the pronunciation. (Student 9)

Associating the auditory style with the listening skill, one can see it is a fact that this skill requires a lot of listening exposition and permanent work to be well-developed. However, many participants stated in the survey that they devoted little time or nothing to strengthen their listening skill. Hence, listening became the most difficult language skill for them. In their responses 10 participants mentioned having this difficulty.

My learning is truncated in speaking and in the listening part. The understanding of listening is too difficult for me. (Student 4, Survey)

Connecting now the impulsive learning style with the verbal skill, one can see speaking was a challenge for them, too. Although the participants had already taken three previous levels, their performance on the oral test was limited; therefore, the lowest grades of several participants, talking about language skills, were not only in listening, but in speaking, too. The study revealed that most participants were not impulsive learners; they disliked talking in English; during classes, it was necessary for the teacher to speak in Spanish very often and use code switching (Skiba, 1997) to achieve more effective communication. Being risky and taking the initiative to express verbally in English was difficult for most participants, since they mentioned being afraid of making mistakes.

To continue relating learning styles to the participants’ linguistic skills, that is, auditory style to the listening skill; visual to reading comprehension; writing, grammar, and vocabulary to reflective-analytical; and impulsive to the speaking skill, the study provided the following information:

Firstly, speaking skill: Twelve participants were not impulsive learners; they experienced high difficulty speaking in class. In fact, they were reflective learners and preferred to think carefully before speaking. Secondly, listening skill: This was also a difficult skill for 10 participants; they were not auditory learners, they were actually visual learners. In third place: Reading comprehension, only four participants had problems when reading and understanding. In grammar: Eight participants had problems when analyzing grammatical rules and scanning. In the last place, vocabulary: Only two students presented trouble for the acquisition of new terms and vocabulary; actually, vocabulary became astrong point for most of them. Consequently, it can be summarized that speaking, listening, and grammar were the language skills that deserved more attention by most participants. The analysis also revealed that one participant had problems with all English linguistic skills.

Lastly, it can be highlighted that few participants used to combine different learning styles such as visual, auditory, musical, and reflective at the same time. Brown (2002) stated that combining styles is a very good decision, since learners are using both sides of their brain hemispheres and retaining data in a better way. Brown held that people usually use one side of the brain more than the other, but they should work both sides and develop both hemispheres: “Left and right sides of the brain have to be worked together as members of a team to be able to stay balanced and learn best” (p. 15). Brown also noted that some learners are left-brain oriented while others are right-brain oriented; they use the left part of their brain more than their right one or vice-versa and have a dominant learning style. Each hemisphere has its own unique and special ability and each one recognizes and processes different issues and realities.

Therefore, the findings evidenced that those few participants learned the language best by making use of several styles and combining learning strategies; for instance, by listening to music, playing dynamics and games, reading, and watching videos or working in Duolingo (an interactive free language-learning platform). Validating this, Coffield, Moseley, Hall, and Ecclestone (2004) also claimed that if learners integrate different learning styles, they will learn better and easier. Additionally, and according to Ortiz de Maschwitz (as cited in Gardner, 1993), learners can be more successful when they also use their multiple intelligences in learning processes (e.g., musical, kinesthetic, linguistic, and so forth) to pose and solve problems, since multiple intelligences are also connected to learning styles. Certainly, these learners may become better problem solvers in life (Biggs, 2001). Consequently, it is undoubtedly useful and even advisable to use different methods, combine learning styles, multiple intelligences, and reinforce the study strategies to acquire a foreign language in a more meaningful way.

Motivation

Bearing in mind important concepts about motivation such as “having a real purpose or desire to learn something” (Brown, 2002, p. 17) and also having “the internal drive that pushes someone to do things in order to achieve something” (Harmer, 2001, p. 51), I saw evidence that many participants had the purpose for learning English very clear. Accordingly, they expressed freely what moved them to learn it.

Nine of the 13 participants (70%) stated they had internal motivation towards English. They indicated being aware of the usefulness of this language. In addition, they expressed wanting to have opportunities to grow professionally, travel abroad, and learn new cultures. They also mentioned they wished to learn and improve their English level to be able to read and understand articles in this language; understand and talk to foreigners fluently, or enjoy the music they liked more. They also mentioned being interested in achieving a good language level to have access to international scholarships or agreements among universities.

Furthermore, several participants believed that learning English could provide them with better professional development.

Because English is the universal language and it almost mandatory to know it nowadays. Furthermore, it is very useful for me throughout my career and in the future for my professional life. (Student 12)

I’m taking English because it opens doors and guaranties a better future. (Student 2)

Well, my motivation is being able to see, read, and understand articles in English. To talk to foreigners and other people in English, listen to music and understand it, and above all, to achieve a good level of English to apply scholarships in another country. (Student 11)

Conversely, four participants (31%) stated having taken English just to fulfill the university graduation requirement:

Sincerely, it is because we have to take the levels for the graduation. (Student 5)

I am taking this course because it is mandatory. (Student 9)

This evidenced that their motivation toward English was extrinsic. As stated by Brown (2002), these learners were pushed by something to learn it.

People study English because it is mandatory or because they need it for ECAES,3 and not because they actually want to or like it. This is the reason why students do not take it with commitment and interest. (Student 19)

People only take it as something they have to fulfill as mandatory. Furthermore, it does not have any academic punishment. (Student 15)

Furthermore, some participants’ viewpoints also revealed that they felt demotivated because English does not belong in their study plan any more and does not affect their academic average.

The reason for my discouragement is that this subject does not have any credits and does not affect the average; for this reason, students are not interested in it, since there are subjects with more relevance that do have credits. (Student 12)

On the other hand, two participants indicated not having had enough time to devote to doing homework or study and so expressed their discouragement.

I get unmotivated because I cannot devote the time I wanted. (Student 11)

I get unmotivated because I simultaneously take other high difficult level subjects which don’t let me concentrate on this course. (Student 17)

Two others declared believing that a foreign language required time and devotion, since sometimes English was not so easy for them. They also recognized the lack of importance given to English by students themselves.

It is discouraging that sometimes students do not give English the importance it deserves, ignoring benefits. (Student 16)

It is discouraging the low commitment students give the subject, since they do not take it seriously. (Student 19)

Moreover, two participants pointed out their preference for having studied English for specific purposes (ESP) than EFL, to be able to learn topics and vocabulary related to their study area and expressed their disagreement with EFL.

I got discouraged since English does not have to do with my program; for this, the interest is not suitable, it is the last subject one takes, the last choice. (Student 6)

Also, because English is very general and I would like to learn vocabulary related to my career. (Student 17)

Other participants also stated that in their academic programs there were major required subjects with credits that demanded their total devotion and attention. For them, all these were the reasons why they had shown low interest toward English and extrinsic motivation; they stated that they had had no choice. Likewise, other participants added that some of them entered university with a low background and bad level of knowledge in English from secondary school.

In conclusion, many participants were mainly motivated externally because of the reasons expounded upon above. However, it is worth remembering that intrinsic is the most effective type of motivation while learning (Brown, 2002; Harmer, 2007) and this is what makes the difference when learning.

Commitment and Students’ Attitude throughout the Learning Process

The study found good attitudes, but also some indifference and low levels of commitment for English learning. Commitment, according to Goffin and Helmes (2000), implies the realization of internal intentions in external actions. Thus, the external actions of some participants indicated a low level of commitment. DeShon and Landis (as cited in Goffin & Helmes, 2000) claimed that commitment is “the degree to which the individual considers the goal to be important, is determined to reach it by expending effort over time, and is unwilling to abandon or lower the goal when confronted with setbacks and negative feedback” (p. 318).

Bearing in mind these concepts and according to the data analysis, one can see that the degree of involvement, effort, and interest of some participants with their process was insufficient. For example, some repetitive attitudes of disregard, laziness, constant nonattendance, and many other excuses by some participants were found. Also, it was also common to evidence low disposition levels. The following entry in the teacher’s diary shows a sample:

Others, on their part, did not show major commitment and simply read from a piece of paper, without taking into account the parameters for oral presentations such as organization: Introduction (development and closing), pronunciation, grammatical correctness, fluency, and creativity. Even they were written on the board. Student 5 was sincere and stated that he had not actually had time to prepare the presentation, since he had had to prepare a test for another major requirement subject...but the other students limited to improvise and do nothing. (Teacher’s diary)

Furthermore, through the responses in the survey a few participants admitted that their interest in the English learning process had indeed decreased over time.

This semester my interest for English decreased, my current level is lower than in previous levels. (Student 12)

My level is actually low, I have not given English enough interest. (Student 15)

In addition, some participants recognized their not having given English the necessary importance.

Well, I have not given it all the importance it deserves; however, I have improved regarding the previous levels. The comprehension has been better and the learning too. The level has increased, not as well as I wanted because of the lack of devotion, but it has indeed improved so much. (Student 4)

At the beginning, I did not give it major importance because of the lack of time, but this semester my teacher has helped me to overcome many difficulties; for this reason, I have improved my skills in front the language. (Student 18)

If I had had more time, I would have been more dedicated and committed. (Student 11)

The analysis also revealed that most participants were aware that a student’s attitude can influence the learning process in an important way; however, in spite of this viewpoint, the actual attitude of some participants was somewhat incoherent with their responses. Little effort or tangible disposition was noticed, considering that most of them were doing their last semesters and English IV was the last level they had to take as a graduation requirement. Several students (9 of the 22) simply made the decision to drop out of the course.

Learning Strategies

According to the survey, Table 2 shows the most common strategies used by the participants. Some of these also revealed certain indifference for English on some students’ part. This issue was also corroborated through the term and registered in the teacher’s diary.

Table 2. Strategies Used by the Participants

The responses in Table 2 show that several participants experienced certain disregard for the strategies proposed. As evidenced, the strategy of asking questions was the best scored; around 50% of participants preferred to ask to solve doubts and over 38% of them used to interact in class and take notes. On the other hand, searching or going to the library was not relevant for them; tutorials were not used at all; the web pages proposed to reinforce learning and expand topics were used by only two students. Furthermore, the extra exercises and workshops designed to complement the topics were developed by only one student. For successful English learning, learners should show more autonomy and interest.

Autonomy

In the study, autonomy was taken as the ability to take charge of one’s own learning (Holec, 1981). Hence, it is relevant to understand that English learning requires constancy, self-motivation, and time devotion.

Initially, all participants stated that the autonomy achieved at university is something beneficial, not only for daily life, but to improve their academic and professional performance. Nevertheless, many responses in the questionnaire, in the survey, and also in some entries in the teacher’s diary revealed that the level of autonomy achieved was not high.

On a scale from 1.0 to 5.0, ten students self-assessed their autonomy as 3.0; two graded their autonomy level achieved during the learning process with 4.0, and one student gave himself a self-evaluation of 2.0. This shows that their self-direction process is failing; they do not have total control of their own process. Furthermore, the time devoted to independent work was not enough, and their dedication to English learning was not significant.

The study showed that 93% of the participants did not devote enough time to working autonomously in English. This means that their independence to work on their English assignments and the time allotted to this was certainly reduced. According to their own perceptions, 12 participants did not study, reinforce, or do homework and only one participant of the 13 dedicated around one hour a day to studying English and doing homework, for a total of six hours a week.

The study concluded that learning a language successfully depends not only on didactic materials, activities, or the teacher. This process also depends on learners’ interest, their self-motivation, and their autonomy, by assuming a more cooperative attitude by both parties.

It was also established that many participants were aware of the benefits of learning English and valued the importance of being involved in the process to succeed; additionally, they were conscious this foreign language is in fact useful in this globalized world nowadays. Conversely, it is necessary to analyze this claim more deeply and to look at the teaching-learning processes from other angles to achieve the change of attitude that we all want in both teachers and students, through a more critical reflection and reciprocal support.

Likewise, most participants recognized their weaknesses related to their study skills and study methods, and evidenced their drawbacks regarding their level of involvement, commitment, and interest during the process. Moreover, some of them stated they had not given English the importance and devotion this deserved. Thus, the factors that participants mentioned as affecting a good performance in English included a lack of motivation, interest, effort, and commitment; plus not having enough time to study and absenteeism.

This study also showed that when learners are asked to reflect, they are quite capable of becoming aware of their deficiencies. Therefore, teachers should implement some sort of reflective practice inside their lessons to identify, together with students, the areas that need improvement. Next, action can be taken to foster motivation or autonomy (or any other relevant aspect), which may ultimately benefit the students’ performance in the foreign language, the overall goal of the learning process.

Complementing this, it was established that some participants also needed to learn how to define priorities and set goals. They felt unsure about how to plan, control, regulate, and self-asses their learning. This lets us see the urgent necessity to develop or strengthen the metacognitive skills and self-regulation processes, which may favor and nurture critical thinking processes, and may assure more effectiveness in learning.

On the other hand, the study also concluded that the most common learning styles used by the participants were visual and analytical-reflective. The least developed styles were auditory and impulsive. Consequently, the auditory and impulsive styles connected to the corresponding linguistic skills of listening and speaking, need to be fostered too.

It was also discovered that those participants who accomplished the best outcomes decided to use several styles and liked to explore new ones, taking advantage of their multiple intelligences such as the linguistic, creative, and musical aspects.

Accordingly, it can be summarized that when developing and combining different learning styles and strategies students may become more effective learners and achieve better outcomes in the process. So, students can combine cognitive strategies such as note taking, test taking, reading techniques, and inference with metacognitive strategies such as planning, monitoring, and evaluating. Oxford (1990) stated that, “a strategy is useful for a student when this relates well to the L2 task, when it fits the particular student’s learning style preferences, and when the student employs the strategy effectively and links it with other relevant strategies” (p. 8). Likewise, students can work these tactics together with social-affective strategies like cooperation or asking for clarification (O’Malley & Chamot, 1990) of partners and teachers.

Finally, dropping out is indeed a concern in public higher education and there can be multiple factors affecting it. The current study corroborated that 59% of participants quit the course throughout the term because of several external and personal factors; some of the personal reasons were insecurity, inconstancy, and fear of making mistakes. Regarding this last, the researcher has experienced through her teaching practice that people learn best from mistakes. Making mistakes is a necessary and very useful process in learning as well as in daily life situations. Therefore, it can be ultimately summarized that keeping a distance from problems and leaving them aside is not the best solution. Academic problems and other particular learning situations must be addressed with patience, sharing or support, and/or specialized help. In the case of students with low aptitude for languages or with learning disabilities, teachers must adjust, vary, and focus their methodological strategies to suit those students’ special needs and thus reach all types of learners.

1Compulsory requirement for the undergraduate degree in Colombia.

2Excerpts have been translated from Spanish for publication purposes.

3Acronym of Examen de Calidad de la Educación Superior. It is a knowledge test applied in Colombia to students who are in the last semesters.

4The questionnaire and the survey were applied in Spanish but have been translated for publication purposes.

Biggs, J. (2001). Enhancing learning: A matter of style or approach? In R. J. Sternberg & L.-F. Zhang (Eds.), Perspectives on thinking, learning, and cognitive styles (pp. 73-120). New York, US: Routledge.

Brown, H. D. (2002). Strategies for success: A practical guide to learning English. New York, US: Longman.

Claxton, D., & Murrell, P. (1987). Learning styles: Implications for improving educational practice (ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report No. 4). Washington, DC: George Washington University. Retrieved from ERIC database (ED293478).

Coffield, F., Moseley, D., Hall, E., & Ecclestone, K. (2004). Learning styles and pedagogy in post-16 learning: A systematic and critical review. London, UK: Learning and Skills Research Centre.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, US: Sage.

Crow, L. D., & Crow, A. (1948). Educational psychology. Ithaca, US: Cornell University.

Dodge, J. (1994). The study skills handbook: More than 75 strategies for better learning. New York, US: Scholastic.

Flavell, J. H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive-developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10), 906-911. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.906.

Gardner, H. (1993). Frames of the mind: The theory of multiple intelligences (10th anniversary edition). New York, US: Basic Books.

Griffiths, C. (2013). The strategy factor in successful language learning. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Goffin, R. D., & Helmes, E. (Eds.). (2000). Problems and solutions in human assessment: Honoring Douglas N. Jackson at seventy. Boston, US: Kluwer Academic Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-4397-8.

Harmer, J. (2001). The practice of English language teaching (3rd ed.). Essex, UK: Pearson.

Harmer, J. (2007). The practice of English language teaching (4th ed.). London, UK: Pearson.

Holec, H. (1981). Autonomy and foreign language learning. Oxford, UK: Pergamon.

Jiménez, P. K. (2015). Exploring students’ reactions when working teaching materials designed on their own interests. Cuadernos de Lingüística Hispánica, 25, 201-222. https://doi.org/10.19053/0121053X.3378.

Kang, S. (1999). Learning styles: Implications for ESL/EFL instruction. English Teaching Forum, 37(4). Retrieved from http://dosfan.lib.uic.edu/usia/E-USIA/forum/vols/vol37/no4/p6.htm.

Lewis, R. B., & Doorlag, D. H. (1999). Teaching special students in general education classrooms (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, US: Prentice Hall.

Little, D. (1991). Learner autonomy: Definitions, issues and problems (Vol. 1).Dublin, IE: Authentic.

Merriam, S. B. (1988). Case study research in education: A qualitative approach. San Francisco, US: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

O’Malley, J. M., & Chamot, A. U. (1990). Learning strategies in second language acquisition. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139524490.

Oxford, R. L. (1990). Language learning strategies: What every teacher should know. New York, US: Newbury House.

Oxford, R. L. (2003). Language learning styles and strategies: An overview. GALA, 1-25.

Oxford, R. L. (2011). Teaching and researching: Language learning strategies. Harlow, UK: Pearson.

Richards, J., & Schmidt, R. (2002). Longman dictionary of teaching and applied linguistics. London, UK: Pearson.

Skiba, R. (1997). Code switching as a countenance of language interference. The Internet TESL Journal, 3(11). Retrieved from http://iteslj.org/Articles/Skiba-CodeSwitching.html.

Smith, C. B. (2000). Reading to learn: How to study as you read. Bloomington, US: ERIC Clearinghouse on Reading, English and Communication.

Thomas, A. (1993). Study skills. OSSC Bulletin, 36(5). Retrieved from ERIC database (ED355616).

Patricia Kim Jiménez holds a B.A. in Modern Languages and an M.A. in language teaching from UPTC. She is a full-time teacher and current coordinator at Instituto Internacional de Idiomas, at the same university.