https://doi.org/10.19183/how.25.1.391

Jennyfer Paola Camargo Celya

aUniversidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas, Bogotá, Colombia. E-mail: jpcamargoc@correo.udistrital.edu.co

Received: June 6, 2017. Accepted: August 29, 2017.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Camargo Cely, J. P. (2018). Unveiling EFL and self-contained teachers’ discourses on bilingualism within the context of professional development. HOW, 25(1), 115-133. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.25.1.391.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. License Deed can be consulted at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Throughout time, the predominant use of certain languages has allowed some nations to take control over others and assure for them a privileged position. This study unveiled how certain practices and ideologies in regard to bilingualism have influenced teachers’ professional development. Data were collected through discussion group sessions, reflective journals, and protocols from five teachers from a private K-11 school in Bogota. Analysis indicated participants’ discourses drew on hegemonic, colonial, and manipulative ideas. Nevertheless, when dialoguing and peer coaching, a discourse of resistance was constituted. The study suggested further research into teachers’ professional growth, bilingualism, and bilingual education in monolingual contexts as the Colombian one.

Key words: Bilingualism, bilingual curriculum, discourses, teacher’s professional development.

A lo largo de la historia, el uso predominante de ciertos idiomas ha permitido a algunas naciones tomar el control sobre otras y asegurar una posición privilegiada. Este estudio reveló cómo ciertas prácticas e ideologías con respecto al bilingüismo han influido en el desarrollo profesional docente. Los datos fueron recolectados a través de sesiones de grupos de discusión, diarios reflexivos y protocolos de cinco profesores de un colegio privado (K-11) en Bogotá. El análisis indicó que los discursos de los participantes se basan en ideas hegemónicas, coloniales y de manipulación. Sin embargo, al dialogar y guiarse mutuamente, un discurso de resistencia se constituyó. El estudio sugiere una investigación más profunda sobre desarrollo profesional docente, bilingüismo y educación bilingüe en contextos monolingües como el colombiano.

Palabras clave: bilingüismo, currículo bilingüe, desarrollo profesional docente, discursos.

The influence of Great Britain and the United States on international relations, political, and economic systems for the last decades, has ensured the acceptance and spread of English as the main language spoken worldwide (Guerrero & Quintero, 2009). Considering this premise, the Colombian Ministry of Education launched the program “la Revolución Educativa” (Education Revolution) and within it the subproject Colombia Bilingüe (Bilingual Colombia), under the vision of offering Colombian students the possibility of becoming bilingual so they could increase their productivity in a globalized world (González, 2007; Guerrero, 2009). However, its implementation has not recognized the complexity of students’ and teachers’ realities, leaving aside internal and external factors that play an important role within the teaching-learning practices (Fandiño-Parra, 2014).

Consequently, English is considered to be an imposition in the Colombian context, where the teaching and learning process became standardized and assessed through rubrics, limiting both students’ and educators’ discourses and practices as foreign bilingual educational programs, which do not rely upon local policies nor teachers’ experiences, have been adopted (de Mejía, 2004). Hence, there is a need of reflecting and assuming a critical stance as regards the adoption of policies and foreign models as well as on relying upon teachers’ experiences and knowledge when developing a bilingual curriculum, allowing teachers’ development and enacting social transformations.

Based on that premise, researching both English as a foreign language (EFL) and self-contained teachers’ discourses towards bilingualism was an opportunity to understand the way participants’ educational practices have been shaped in relation to the bilingual policies adopted by the Colombian government. Moreover, it established an opportunity to conceive professional development beyond formal training but as an ongoing process of reexamining beliefs and practices to transform the inside and outside of the classroom by means of sharing and relying upon colleagues.

As stated by Fairclough (2003), language is a social practice where discourses, both written and oral, are created, understood, shaped, and validated within a community in a specific context by means of interaction. In the same line of thought, Kumaravadivelu (2003) affirmed discourses reflect a fragment of the world that is only understood by addressing the context where they are produced in relation to the participants and their intentions.

Discourses around bilingualism draw upon the new capitalism notion, an economic system based on the production of goods and services characterized by competition and unlimited consumerism (Fairclough, 2003; Guerrero, 2008; Usma, 2009). In this manner, education, by being controlled and limited, becomes intone of the main tools with which to practice power, which is exercised through the systems of knowledge (Foucault, 2005). Hence, the principles of what should be known (didactics and learning theories) and the way it should be learned (curriculum) are consequences of power that enclose not only the possibilities of the present but of the future, as they both serve as foundations for shaping teachers’ and learners’ view of the world (Popkewitz, 2000).

Consequently, the language policies adopted by the Colombian government were meant to spread EFL under structured standards having as a result more constraints than advantages (Ayala Zárate & Álvarez, 2005). The first constraint refers to the fact that this foreign model has been perceived as an imposition rather than as an adoption. Guerrero’s (2008, 2009) and Guerrero and Quintero’s (2009) works have revealed that the documents supporting the bilingual policies carried out by the government favored and recognized English as the language of modernization and progress, taking no notice of Colombia’s diversity in terms of languages (e.g., creole and indigenous). Indeed, a similar situation is being evidenced with Spanish which, as claimed by de Mejía and Fonseca (2006) and Ordóñez (2011), has been relegated to a lesser status by educational institutions as the focus of bilingualism is on achieving a high level of proficiency in English.

The second constraint refers to the implementation of foreign models unrelated to Colombia’s geographical conditions, learners’ characteristics, and the particularities of the educational system. As reported by Ayala Zárate and Álvarez (2005), this has led to negative implications for the EFL teaching and learning processes since the foreign language is conceived as a standardized linguistic system, reinforcing the idea that bilingualism can be measured and validated through rubrics. Thirdly, the EFL teaching process has been outshone given that teachers were not part of the decision-making process or the design of language policies, and that the foreign entities in which the government trusts, bring professional growth under their control as they determine “who is competent to teach the language and how these individuals should teach” (Escobar Alméciga, 2013, p. 47).

The fourth concern deals with the breach that bilingual policies broaden between private and public education. As report by Miranda and Echeverry (2010), public education is left behind as the infrastructure, materials, and L2 exposure—in order to reach bilingual standards—are not provided by the government, and the economic resources of these students are not enough to have access to them.

Accordingly, there is a need to take a critical stance concerning bilingualism so as to co-construct bilingual curricula that meet students’, EFL, and self-contained1 teachers’ realities. To do so, self-reflection on educational theories and perspectives and the way these are carried out is necessary (Murray, 2010). This process, as stated by Díaz-Maggioli (2004) is a process implemented not only for professional but also for personal reasons, as even though this is decided and carried out by the teacher him/herself, it has an incidence in the students and the community.

In this sense, sharing with and relying on colleagues are essential moves for teachers to become active participants in the teaching learning process, exploring and learning new ideas and concepts, and making decisions based on their own and others’ experiences and understandings as demonstrated in Ordóñez’ (2011) and González’ (2007) studies with Colombian teachers. Considering Wheatley’s (2002) work about teachers’ efficacy doubts—a term that fosters teacher learning by reflecting and promoting collaboration—exchanging ideas with colleagues also helps teachers to confirm, reject, or suspend judgments of new interpretations and encourages them to become aware not only of their practices but of the effect of those. Therefore, teaching is not just a practice developed within a society, but it has a responsibility that comes with it.

In keeping with this idea, Wenger (1999) declares that learning by means of sharing and participating with others, “shapes not only what we do, but also who we are and how we interpret what we do” (p. 4), implying that both learning and teaching are social practices embedded in and developed within a group. Therefore, belonging to a community of practice (Wenger, 1999) allows teachers to redefine their practices, to get engaged in the construction of knowledge and to improve their and their learners’ realities at the time of endorsing professional development. Hence, this study addressed the need of making teachers’ voices visible about bilingual policies and practices as well as the importance of resisting discourses that prolonged social inequality and injustice inside and outside the classroom so as to enact change.

As previously discussed, it seems relevant for the EFL community to reflect and assume a critical perspective about the adoption of policies and foreign models as well as the way they are reflected within the teaching-learning process. Therefore, a pedagogical intervention was envisaged under the belief that bilingual education in Colombia must be conceived beyond the premise of just learning English or achieving the goals proposed by the government, but also as an opportunity to listen to educators’ voices in relation to policies and curriculum design. Incidentally, the aim embraced individual and collective opportunities to grow professionally by rethinking, evaluating, and renovating educators’ teaching practices, moves which allowed them to position themselves as active members of the educational process.

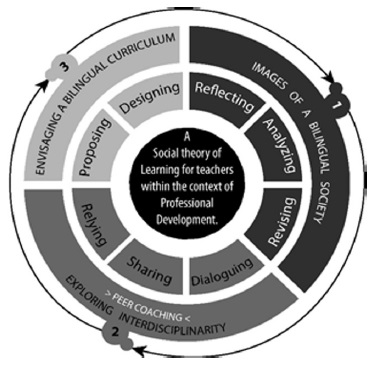

Within this process, it was evidenced that related aspects such as interaction, negotiation of meaning, and collaboration regulated participants’ desire and commitment of belonging. Likewise, the stages proposed supported the idea of professional development as a cyclical and reciprocal process of learning by drawing upon participants’ immediate context and experiences, a condition that in Díaz-Maggioli’s view (2012) can positively affect what happens in and outside the classroom as the teaching process is the result of personal, professional, knowledge, institutional, and curriculum factors. Figure 1 displays the way this pedagogical intervention was conceived.

Figure 1. Instructional Design Stages

As seen in Figure 1, the stages of this pedagogical intervention elucidate a process of reflecting upon pedagogical and personal practices in regard to bilingualism and bilingual education. In this sense, the intention of this intervention was firstly, to make both EFL and self-contained teachers aware of this phenomenon, and secondly, to enact active participation in the development of a curriculum by addressing both learners’ and teachers’ needs. In doing so, teachers have an opportunity to empower themselves and others via sharing and discussing (Murray, 2010). In this sense, the first stage aimed at revising the conceptualization of the terms bilingualism and bilingual education to then analyze the way these notions have been institutionalized and assumed in our context. Listening and debating were key aspects to either shape or reject previous ideas. The second stage focused on endorsing participants’ professional development by highlighting the practices of dialoguing and sharing personal and professional experiences so as to generate new ways of thinking about bilingual practices in Colombia.

This stage was also essential in terms of transforming and enlightening pedagogical practices since through peer coaching (Díaz-Maggioli, 2003), participants realized the importance of relying upon colleagues to integrate knowledge. Visiting the classes of the other participants seemed highly worthwhile as new methodologies, activities, and how to monitor learners’ knowledge were learnt. Opposite to the traditional vision described by Richards and Farrell (2005), the peer coaching strategy did not intend to supervise or evaluate teachers’ knowledge but for them to learn from each other. This was possible as non-hierarchical social relationships among participants were established, so that the principles supporting this strategy were reliance, learning, and transformation. Hence, both teachers—one who observed (coach) and one who was being observed (coached)—were encouraged to reflect and to link their own pedagogical practices to what had been discussed in the first stage, constituting then a collaborative peer coaching which in Fahim and Mirzaee’s (2013) view, allows teachers to be more creative and aware of new teaching styles.

In addition, this tool allowed participants to reinforce the idea of approaching bilingual practices from a social perspective as well as making them understand and assume an active role within this practice regardless of their area of knowledge—either EFL or self-contained—by means of dialoguing. This last argument was examined and evidenced in the last stage where the teachers had the opportunity to picture a bilingual curriculum aimed not only at language proficiency, but also at awareness on sociocultural issues. Naturally, their proposal considered the school’s identity, the Proyecto Educativo Institucional (the institution’s educative project) and the ideas that resulted from discussing and interacting. Figure 2 displays the bases of this proposal considering the information obtained in the discussion group sessions and Protocol 2.

Figure 2. Participants’ Proposal

Setting and Participants

This study took place at a private school in an upper-middle-class neighborhood in the Usaquén location in Bogota (Colombia). The school claims to be bilingual regardless of not having a bilingual curriculum. Participants were four high school teachers and one elementary school teacher. They are referred to in the study by the pseudonyms of Mrs. L., Mrs. P., Mrs. C., Mrs. N., and Mrs. J. All five females’ ages ranged from 25-44. The first three are self-contained teachers while the last two are EFL teachers.

Data Collection Instruments and Procedures

The data collection process was done within the natural setting of the case (Shagoury & Miller, 1999). Data were collected within a 12-week period where both EFL and self-contained teachers met for about an hour, mainly on Mondays. As this study is qualitative in nature, data were collected through three means: discussion group sessions, protocols, and teachers’ reflective journals. The first instrument is a technique in which meaning is constructed among participants from a particular setting (Martín Criado, 1997). In this sense, the researcher’s role is not limited to posting a topic to be discussed or to structuring the conversation, but to participating and reacting towards the ideas generated there. The comments and ideas were tape-recorded.

In addition, two protocols were proposed for the first and third sessions in order to capture participants’ ideas before and after discussing bilingualism and bilingual education. Both protocols (see Appendix) were taken and adapted from Barkhuizen and Wette’s (2008) work on narrative frames. Regarding the reflective journals, they addressed inside and outside factors that might have an influence on the teaching-learning process. Likewise, this strategy, as described by Díaz-Maggioli (2004), provides a way for professionals to focus on and document their own professional development. In that sense, participants’ journals did not have any particular structure or guidelines to follow other than being written and collected at the end of each session so as to ensure that the ideas emerging from the discussion group were communicated in a spontaneous manner.

According to Jørgensen and Phillips (2002), discourse analysis as a method aims at an understanding of discourses as a social phenomenon. Therefore, both participants and their discursive practices were analyzed with the intention of understanding the way meaning in relation to bilingualism was constructed and mediated. As this research aimed at unveiling EFL and self-contained teachers’ discourses on bilingualism within the context of professional development, it became necessary to implement the qualitative content analysis (QCA) in order to describe the meaning of data and to establish insightful relationships among data that could contribute to both research fields: discourse studies and teacher professional development.

Besides, it was relevant to understand participants’ social reality by going beyond the mere fact of counting words or extracting objective content from texts. As a result, I was able to examine not only the relationships among concepts in a text but to reveal the means through which individuals recognize and experience themselves as members of a community. Hence, to analyze EFL and self-contained teachers’ discourses regarding bilingualism from this perspective is to understand the relationship among discourse, social practices, and the teaching-learning process.

Similarly, participants’ professional development construction through the exercise of sharing, reflecting, and dialoguing could be portrayed by using this method as it produces descriptions or typologies along with expressions from subjects reflecting how they see and perceive themselves within the social world (Zhang & Wildemuth, 2005). Figure 3 displays the stages followed to analyze data.

Figure 3. QCA Data Analysis Stages (Zhang & Wildemuth, 2005)

It is important to state that as this research dealt with a great amount of data, I decided to use the Atlas.ti software to systematize, control, and organize step-by-step the text analysis. At the end of this process, two main categories emerged with a view to giving an answer to the research question leading this work. The first category describes how the phenomenon of bilingualism in Colombia has been the result of the government’s and foreign entities’ efforts to assure international links regarding politics and the economy through education (Escobar Alméciga, 2013; Guerrero, 2008; Valencia, 2013).

First Category: Bilingualism as a Phenomenon of Social Control

Most of these discourses deal with the ideas of success, economic stability, access to qualified education, and trading. In this sense, English has been designated as the language to be learnt and foreign entities are in charge of developing the appropriate methodologies and materials to do so, influencing practices in schools and universities (Guerrero & Quintero, 2009).

This is evidenced in the following excerpt, in which the participant enlightens one as to how the educational practices in terms of bilingualism are limited to teaching English so as to access industrialized technology and qualified knowledge. Likewise, it reflects how some features in relation to the capitalism discourse have become naturalized and are reinforced in the classroom (Foucault, 2005).

Well, I would say because it is mainly about trading, about who the dominant country is and if you want to succeed in life, you must know English, why? Because you, because everything that comes here, everything that is knowledge, everything that refers to technologies and all this kind of things are developed in countries where English is spoken, what happens then? Then, in Colombia it is wanted, it is wanted that students speak English so they can go and get trained there so we can handle the technology that is done there so we can apply it. (Mrs. N, Discussion Group Session 2)2

As noticed in the second line, the conditional statement gives account on how this participant conceives learning English as a vital aspect to do well in life, which is translated into having better incomes and getting access to advanced knowledge which, of course, is deemed as being only produced in the dominant country. By asserting this, an opposite discourse in terms of the knowledge and the technology developed or constructed in our country (or any that is not the dominant one) is generated.

In this sense, the participant is drawing on hegemonic discourses as the idea supported is that people cannot succeed unless they reproduce what is done or said by others, which in her words is to be “trained”, a concept that has assured the powerful countries of exercising economic control over the developing ones (Kachru, 1992). Likewise, it was observed that the participants’ discourses, in relation to the phenomenon under study—bilingualism—were centered on English prevalence and its importance over other languages, including their mother tongue. This ideal, as described by Pennycook (1998), is rooted in colonial discourses that served to be the foundation of some of the central ideologies of current English language teaching, where the foreign language is promoted under the premise of being superior to other languages. The next excerpt, displays the previous avowal.

Mrs. C: I consider the way bilingualism has been seen for many years is good, that second language, and English has been reinforced without diminishing other languages as seen in many educational institutions when it is either French, German, Mandarin, but English has been taken as a reference point to precisely make an exchange not only in terms of knowledge as a language base but also as a cultural exchange seen from Colombia, where there are many people coming from other regions of the world where English is spoken regardless of whether it is a British English or...

Mrs. J: American?

Mrs. C: or American then is as that ideal not only seen from the Colombian politics to make a bilingual Colombia from the youngest up to the adults in different contexts but also as a way to look for exchange eh cultural, scientific, among other areas with these countries. (Discussion Group Session 1)

The first affirmative sentence implies that bilingualism is a concept that has been present in our country for a good while and that this participant agrees with the notion given to it in the Colombian context, which as previously discussed, is limited to the fact of speaking English. This last premise is reinforced when acknowledging that even though there are more languages being taught in different institutions, English is the one that allows citizens to have cultural and scientific exchange and, in that sense, the policies carried out by the government are acceptable. The Colombian government through educational material such as the Estándares3 (Ministerio de Educación Nacional, 2006) has promoted this discourse of manipulation, as reported by Guerrero and Quintero (2009). This will explain then the fact that both participants restricted the linguistic variation of English to the American and British ones, a common phenomenon that in Kachru’s view (1992) allows countries from the inner circle to exercise economic control over the countries from the expanding circle. As a result, citizens are subjected to learn and teach this language while being positioned as followers. The following excerpt evidences this assertion:

And it is sad that it is just English; it is not that you say if I like romance languages then I will study French and that, but no, we say I don’t care, why? Because most of the people worldwide speak English. (Journal Entry 3, Mrs. P)

As read in the first line, it seemed as if Mrs. P was somehow showing her disagreement with the fact of having to learn English. Nonetheless, her words “I don’t care” suggest somehow indifference and acceptance towards this circumstance, a contrast that could also be identified by the use of the conjunction but. Hence, it could be said that she draws upon colonial discourses as she holds strong views towards learning the foreign language due to its ideal status and worldwide acceptance; features that reinforce the idea of English supremacy, where its relevance and influence is unquestionable and it rather turns out to be a common sense matter. As well, her statement constitutes hegemonic discourses as ideas, meanings, and values are experienced as absolute reality and are designated to influence the decisions, thoughts, and actions of others (Tollefson, 2000). The intention of reproducing these discourses in relation to bilingualism then will always favor English over other languages.

With this in mind, it could also be asserted that not knowing the language would presuppose a negative effect on an individual’s self-esteem. However, the following sample, a fragment of a journal entry, shows us how speaking English could also lead to a negative effect on teachers’ personal and professional identities as aspects such as competitiveness and language proficiency tests have increased.

Most of the people I have talked to since I was in the school, agreed on the fact that speaking English will give us a lot of opportunities both professional and personally, but now that I have had the opportunity to study it as a major, I realize that the opportunities are not so great: Our salary is not increasing as time passes by; we have more competence than ever before, we are forced to accept teaching other classes as social studies, math, or science even though we were not prepared for that and we have to take tests to demonstrate that we really studied and know English. (Reflective Journal Entry 1, Mrs. J)

Taking this into account, one sees it could be asserted that either speaking English or not, citizens from the expanding circle do not experience the same opportunities to triumph in terms of their personal and professional life than the ones belonging to the inner circle (Kachru, 1992). The next piece of data evidences, first, how the conception of bilingualism under hegemonic and colonial discourses indulges native English speakers within monolingual contexts over local teachers and, secondly, how this assumption has led teachers to wonder whether or not to continue being educators.

It is to think that the native speaker is better, I do not know if you knew that two years ago a foreigner came to this school, a gringo, to teach science in elementary and obviously he spoke English so everybody thought he was like Super Peter, and when the guy arrived to the school he did not do anything, he did not prepare [the lessons] or anything at all, but as he was an American native no one said anything, and that happens in Colombia, they bring foreign teachers, gringos, and they do not know anything at all about pedagogy but they’re still teaching in bilingual schools. (Discussion Group Session 2, Mrs. L)

As declared by Mrs. L, the fact of being a native speaker within a country as ours is synonymous with getting job opportunities regardless of having or not having a degree. Likewise, it gives us a look at the way educational and governmental actors position them above local teachers in terms of expertise, which reinforces the idea of native English speakers’ superiority, as her words “Super Peter” denote. González and Sierra (2005) described parallel results in their study with eighteen Colombian teachers who give account of their professional alternatives to achieve higher standards in their jobs.

Second Category: The Art of Questioning, Reflecting, and Envisioning

With reference to the second category, it designated the process in which participants were involved in order to resist the hegemonic, colonial, and manipulative discourses previously identified, allowing them to be empowered and engaged in critical praxis (González, 2007). By doing so, their voices in terms of curriculum design and bilingual education became heard. The participants in this study showed that questioning, reflecting, and envisioning are main issues within general education and professional growth.

Participants’ voices also denote the means of looking into both the past and the present to picture a future; actions that according to authors such as Johnson and Golombek (2002) and Biesta and Tedder (2007) suggest reflecting on experiences, making sense of a phenomenon, and constructing agency. The following excerpt reveals, firstly, the way the bilingualism concept is co-constructed by means of interaction and, secondly, the way this practice reshaped or confirmed educators’ beliefs in relation to the phenomenon under study.

Mrs. C: The schools have to be clear as well by saying whether they are bilingual or if they have intensive English because they sell the idea of being bilingual when they just have an emphasis and in many institutions this happens.

Mrs. J: But then we will have to look at the way bilingualism is being measured.

Mrs. C: Exactly.

Mrs. L: If it can be measured because I cannot say that.

Mrs. C: If it can be measured.

Mrs. L: I cannot say that here the bilinguals are not really bilinguals because as Mrs. P. said, the use of the mother tongue is omitted and suppressed then it is not bilingual.

Mrs. C: Exactly.

Mrs. J: It is still being monolingual but in a foreign language, then the concept of bilingualism is really wrong because everybody is [bilingual], here the bilingualism is only associated with the fact of speaking English.

Mrs. P: Yes.

Mrs. N: It is what you said about the Wayuu, because [their knowledge] is not acknowledged.

Mrs. P: I mean many children speak Wayuu and they have to arrive due to different factors, for displacement, or well, different factors they arrive to a, what is it called? To a community, to a school, and Spanish is being imposed which is traumatic for them and English, and they are not acknowledged as bilinguals because they have an indigenous language.

Mrs. J: Of course.

Mrs. N: Then the concept of bilingualism is not there, there is only one, speaking English and that is it, there is nothing else. (Discussion Group Session 1)

As evidenced, the process of co-constructing the concept of bilingualism was given by means of interaction. To do so, elements from participants’ immediate and common contexts were used to exemplify the practices regarding the phenomenon under study as well as being able to establish a consensus. This peer dialogue, as established in Nielsen, Triggs, Clarke, and Collins’ (2010) research, encourages participants to generate new ways to think about the practicum and their work with the other teachers. The following journal entry presents this EFL teacher’s concerns about the way bilingual education is conceived in Colombia and her personal and professional commitment to change.

I guess most of us just believe what they say, that if we are certified or if we achieve the Estándares or follow the methodology and books provided by the publishing houses we will be better...but better for whom? What for? Certainly not for the students nor the teachers...yes of course, some students like that and learn that way, but other find it boring...I hate working on grammar or being pressed by the international test scores...and I guess not all the teachers like doing that, but I guess we do not have enough spaces to discuss these things, we do not get together to talk about methodology or tools or government decisions that of course affect us even though we are not “public schools” so we do not care much about doing other stuff that are most of the time, time consuming. I like this time with my colleagues, it feels refreshing and useful, I feel better and try to do better my job based on what we have discussed and learn, I think we have an excellent opportunity to make a change, at least for us since I suppose as always, nobody is going to listen or appreciate what we are trying to do. (Journal Entry 3, Mrs. J)

Mrs. J. posted two questions with answers that seem to give account of the reflection process she followed after dialoguing with her peers, as her words are opposite to the success and benefits promoted through those colonial and hegemonic discourses. Similarly, she recognized the importance of working together and relying upon others to improve and enrich pedagogical practices. In addition, the participant acknowledged the fact of being aware of bilingualism policies regardless of the school category—a claim made by many Colombian researchers.

Because she used positive adjectives in the last lines, it could be asserted that by sharing experiences and knowledge that has been significant for each teacher during the process, it became significant as well. Likewise, it gives account as to how encountering constructive experiences with colleagues is a powerful tool to encourage teachers to face discourses and practices that aim at diminishing them as professionals, as stated in her final sentence. Thus, sharing, dialoguing, and witnessing others’ pedagogical practices heighten teachers’ personal and professional identities as they become aware of the role of others, developing a sense of change contained by their opinions and actions (Harré, 1993). Likewise, collaborative work among peers can be seen as a very fruitful interaction to learn from, since it provides opportunities to develop teacher leadership, enhances student learning, and promotes school success (Wang, 2013).

The following excerpt displays how the peer coaching strategy was an opportunity for teachers to learn and grow, as they were able to explore new and contextualized methodologies, materials, and strategies.

I visited Mrs. L’s class in which she was deepening in the concepts of the bio...the bio-elements, and let’s say that I really liked something that I believe is not only useful for a bilingual project but for another, let’s say, another context, and it is the use of technology because she played a video in English which it was explained in a very graphical way, very clear to students, what the bio-elements were and their function in the human body and all these things, so it will be the aspect I would emphasize the most, that for any topic it is good to use audiovisual aids that take out the abstract sense of the concepts, because when saying bio-element no one does necessarily relate it easily to what it is, with the real life, and with the video she used, it was done, and obviously the teacher, she did the synthesis, the reflection, the feedback about what we saw in the video and this is what happens in real life, and how that is located in the periodic table, and like that, right? It is like that way of uniting, of linking what students know in real life with the theory. (Discussion Group Session 8, Mrs. N)

Considering the sample below, it could be avowed that by envisioning a contextualized bilingual curriculum in which different content area teachers are involved, the participant believes that not only a significant contribution in terms language development might be made, but also one to the integration of knowledge, which indeed, will benefit not only learners and educators, but the school itself. Above and beyond, teachers—regardless of their nature—are acknowledged as designers, planners, evaluators, and agents of change, roles that considering Johnson and Golombek’s view (2002), have been denied by the fact of being perceived as objects of study rather than as knowing professionals.

I think that in the school where I work at nowadays, we could develop a bilingual proposal by articulating a curriculum based on the science and technology development and its impact on societies and aspects such as planning, organizing and executing the proposal with a team of teachers from all the content areas should be considered as well as clear policies regarding the implementation of a bilingual project. This could be beneficial for the institution, the teachers, and the students as it would be the beginning of a project articulated to the curriculum and based on the educational community and country real needs. (Protocol 2, Mrs. L)

Overall, the discourses both EFL and self-contained teachers draw on in relation to bilingualism are grounded on hegemonic, colonial, and manipulative notions that circulated and are accepted both naturally and worldwide due to economical commodities. Henceforth, this phenomenon has been limited to the English language, which has had an effect on local participants’ pedagogical practices and personal and professional identities. Nonetheless, by working together, both EFL and self-contained teachers can resist discourses that have been perpetuated through the EFL teaching-learning process in Colombia, as they acknowledged themselves as designers of curriculum and methodologies dealing with sociocultural and scientific perspectives.

It is important to highlight the urgency of understanding the powerful linkage between political and socioeconomic forces in regard to bilingualism and its influence in the educational practices. What is more, having both EFL and self-contained teachers as participants allowed them to find their voices with respect to a specific concern that has been believed to be exclusive of the EFL/second language acquisition field, as claimed by Pennycook (1998).

Considering the outcomes, it can be asserted that participants’ discourses in regard to bilingualism are grounded in hegemonic, colonial,and manipulative ideas, favoring English over other languages. Data revealed that this assumption had a direct impact on participants’ personal and professional identities, since their world, language, and different roles have been modeled and limited, influencing their classroom practices (Piliouras, Plakitsi, & Nasis, 2015).

Nevertheless, it was shown participants somehow resisted these discourses by being involved in a community, where they had the opportunity of firstly, reshaping, contradicting, confirming, and constructing pedagogical beliefs and practices by means of dialoguing and sharing; and secondly, of de-privatizing their pedagogical practices while supporting the group’s individual and collective professional development.

Similarly, it was found that the dynamical process they went through along this research, enabled self- and others reflection upon the bilingualism phenomenon and gave account of their active thinking and decision-making process by drawing on local contexts, learners’ needs, language status, and citizenship. Bearing this in mind, one can see this research calls attention to being aware and taking a stance on the way discourses and practices in regard to bilingualism are being perpetuated—even by us—and secondly, on the need of researching and developing different strategies to enhance teachers’ professional development.

1The self-contained teacher is the one responsible for the instruction of more than one academic subject.

2The excerpts have been translated for publication purposes.

3A document proposed by the Colombian government for the teaching of English process in elementary and high school education. The document draws on the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages.

4Protocols 1 and 2 were applied in Spanish but have been translated for publication purposes.

Ayala Zárate, J., & Álvarez, J. A. (2005). A perspective of the implications of the Common European Framework implementation in the Colombian socio-cultural context. Colombian Applied Linguistics Journal, 7, 7-26.

Barkhuizen, G., & Wette, R. (2008). Narrative frames for investigating the experiences of language teachers. System, 36(3), 372-287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2008.02.002.

Biesta, G., & Tedder, M. (2007). Agency and learning in the lifecourse: Towards an ecological perspective. Studies in the Education of Adults, 39(2), 132-149. https://doi.org/10.1080/02660830.2007.11661545.

de Mejía, A.-M. (2004). Bilingual education in Colombia: Towards an integrated perspective. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 7(5), 381-397. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050408667821.

de Mejía, A.-M., & Fonseca, L. (2006). Lineamientos para políticas bilingües y multilingües nacionales en contextos educativos lingüísticos mayoritarios en Colombia. Retrieved from http://www.colombiaaprende.edu.co/html/productos/1685/articles-266111_archivo.pdf.

Díaz-Maggioli, G. (2003). Professional development for language teachers. ERIC Digest. Retrieved from http://unitus.org/FULL/0303diaz.pdf.

Díaz-Maggioli, G. (2004). Teacher-centered professional development. Alexandria, US: ASCD.

Díaz-Maggioli, G. (2012). Teaching language teachers: Scaffolding professional learning. New York, US: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers.

Escobar Alméciga, W. (2013). Identity-forming discourses: A critical discourse analysis on policy making processes concerning English language teaching in Colombia. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 15(1), 45-60.

Fahim, M., & Mirzaee, S. (2013). Peer coaching: A more beneficial and responsive inquiry-based means of reflective practice. International Journal of Linguistics, 5(3), 245-254. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijl.v5i3.3935.

Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing discourse: Textual analysis for social research. London, UK: Routledge.

Fandiño-Parra, Y. J. (2014). Bogotá bilingüe: tensión entre política, currículo y realidad escolar [Bilingual Bogotá: Tension between policy, curriculum and actual conditions in the schools]. Educación y Educadores, 17(2),215-236. https://doi.org/10.5294/edu.2014.17.2.1.

Foucault, M. (2005). El orden del discurso (A. González, Trad.). Barcelona, ES: Tusquets Editores.

González, A. (2007). Professional development of EFL teachers in Colombia: Between colonial and local practices. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 12(18), 309-332.

González, A., & Sierra, N. (2005). The professional development of foreign language teacher educators: Another challenge for professional communities. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 10(1) 11-39.

Guerrero, C. H. (2008). Bilingual Colombia: What does it mean to be bilingual within the framework of the national plan of bilingualism? Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 10(1), 27-45.

Guerrero, C. H. (2009). Language policies in Colombia: The inherited disdain for our native languages. HOW, 16(19, 11-23.

Guerrero, C. H., & Quintero, Á. (2009). English as a neutral language in the Colombian National Standards: A constituent of dominance in English language education. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 11(2), 135-150.

Harré, R. (1993). Social being (2nd ed.). Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers.

Johnson, K. E., & Golombek, P. R. (Eds.). (2002). Teachers’ narrative inquiry as professional development. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Jørgensen, M., & Phillips, L. (2002). Discourse analysis as theory and method. London, UK: Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849208871.

Kachru, B. B. (1992). Teaching world Englishes. In B. B. Kachru (Ed.), The other tongue: English across cultures (2nd ed., pp. 355-366). Urbana, US: University of Illinois Press.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2003). Beyond methods: Macrostrategies for language teaching. New Haven, US: Yale University Press.

Martín Criado, E. (1997). El grupo de discusión como situación social. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas, 79, 81-112. https://doi.org/10.2307/40184009.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional. (2006). Estándares básicos de competencias en lengua extranjera: inglés. Formar en lenguas extranjeras: el reto. Retrieved from http://www.colombiaaprende.edu.co/html/mediateca/1607/articles-115375_archivo.pdf.

Miranda, N., & Echeverry, Á. P. (2010). Infrastructure and resources of private schools in Cali and the implementation of the Bilingual Colombia Program. HOW, 17(1), 11-30.

Murray, A. (2010). Empowering teachers through professional development. English Teaching Forum, 48(1), 2-11.

Nielsen, W., Triggs, V., Clarke, A., & Collins, J. (2010). The teacher education conversation: A network of cooperating teachers. Canadian Journal of Education, 33(4), 837-868.

Ordóñez, C. L. (2011). Education for bilingualism: Connecting Spanish and English from the curriculum, into the classroom, and beyond. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 13(2), 147-161.

Pennycook, A. (1998). English and the discourses of colonialism. London, UK: Routledge.

Piliouras, P., Plakitsi, K., & Nasis, G. (2015). Discourse analysis of science teachers’ talk as a self-reflective tool for promoting effective NOS teaching. World Journal of Education, 5(6), 96-107. https://doi.org/10.5430/wje.v5n6p96.

Popkewitz, T. S. (2000). The denial of change in the process of change: Systems of ideas and the construction of national evaluations. The Educational Researcher, 29(1), 17-30. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X029001017.

Richards, J. C., & Farrell, T. S. C. (2005). Professional development for language teachers: Strategies for teacher learning. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667237.

Shagoury, R., & Miller, B. (1999). Living the questions: A guide for teacher-researchers. Portland, US: Stenhouse Publishers.

Tollefson, J. W. (2000). Policy and ideology in the spread of English. In J. K. Hall & W. G. Eggington (Eds.), The sociopolitics of English language teaching (pp. 7-21). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Usma, J. A. (2009). Education and language policy in Colombia: Exploring processes of inclusion, exclusion, and stratification in times of global reform. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 11(1), 123-142.

Valencia, M. (2013). Language policy and the manufacturing of consent for foreign intervention in Colombia. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 15(1), 27-43.

Wang, L.-Y. (2013). Non-native EFL teacher trainees’ attitude towards the recruitment of NESTs and teacher collaboration in language classrooms. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 4(1), 12-20. https://doi.org/10.4304/jltr.4.1.12-20.

Wenger, E. (1999). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge, UK. Cambridge University Press.

Wheatley, K. F. (2002). The potential benefits of teacher efficacy doubts for educational reform. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18(1) 5-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00047-6.

Zhang, Y., & Wildemuth, B. M (2005). Qualitative analysis of content. Analysis, 1(2), 1-12.

Jennyfer Paola Camargo Cely holds a Master Degree in Applied Linguistics from Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas. She is currently an EFL teacher at a private university in Bogota. Her interests are in the fields of bilingualism, professional development, and the reading comprehension process.

Co-Constructing the image of Bilingual Colombia

Protocol 1

I am a _______________ teacher and teach _____________ students. Bilingualism for me is _______________________________________________. Hence, bilingual education is _________________________________. The school where I currently work at conceives bilingual education as ______________________________________________________________ since the bilingualism proposal is focused on _________________________________________________________________________. My role in this proposal was _________________________________________________________________________, since ____________________________________________________________________. I consider positive of this proposal _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________. On the other hand, a disadvantage is ____________________________________________________________. I believe that in the future things could be implemented _________________________________________________________________________.

Protocol 2

After discussing the concepts of bilingualism and bilingual education with my colleagues I have concluded that __________________________________________________ and that the National Bilingual proposal is _____________________________________________. This policy has influenced my teaching practices in a ______________________ way ___________________ since ______________________________________________. Likewise, my professional teacher development has _________________________________________________________. I think that in the school where I currently work we could develop a bilingual proposal based on _____________________________________________ and taking into account aspects such as ______________________________________________________. This could be beneficial to _______________________________________________________________ because __________________________________________________________________.