https://doi.org/10.19183/how.25.2.400

Diego F. Ubaquea

Fredy Pinillab

aCentro Colombo Americano and Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá, Colombia. E-mail: dubaque@javeriana.edu.co

bCentro Colombo Americano, Bogotá, Colombia. E-mail: Samcastellanos.sc@gmail.com

Received: July 4, 2017. Accepted: January 31, 2018.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Ubaque, D. F., & Pinilla F. (2018). Exploring two EFL teachers’ narrative events regarding vocabulary teaching and learning. HOW, 25(2), 129-147. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.25.2.400.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. License Deed can be consulted at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This paper summarizes the results of a collaborative narrative inquiry study conducted by two teachers in an English as a foreign language classroom in Bogota, Colombia. The study places emphasis on teacher learning as a reflective practice to contribute to students’ vocabulary learning. However, the analysis presented in this paper is grounded on teachers’ narrative events to understand their experiences teaching vocabulary over communicative classroom activities. Findings revealed that teachers could claim ownership of their own teaching practice when there is negotiation and collaboration of teaching practices over vocabulary activities; furthermore, data made evident that when collaboration emerges as a driving force, teachers’ learning can become relevant to increase students’ learning since reflection is used to adapt teaching to get learning outcomes.

Key words: Collaboration, experience, narrative inquiry, reflection.

Este documento resume los resultados de un estudio de investigación narrativo realizado por dos profesores de inglés en un aula de clase en Bogotá, Colombia. El estudio hace énfasis en el aprendizaje del maestro como práctica reflexiva para contribuir al aprendizaje de vocabulario de los alumnos. Sin embargo, el análisis presentado en este artículo se basa en eventos narrativos narrados por los profesores para comprender sus experiencias de enseñanza de vocabulario sobre las actividades de clase comunicativas. Los resultados revelaron que los maestros pueden reclamar la propiedad de su propia práctica docente cuando hay negociación y colaboración de las mismas prácticas de enseñanza sobre las actividades de vocabulario. Además, los datos ponen de manifiesto que cuando surge la colaboración como fuerza conductora, el aprendizaje del docente puede ser relevante para incrementar el aprendizaje de los estudiantes ya que la reflexión se utiliza para adaptar la enseñanza a los resultados de aprendizaje.

Palabras clave: colaboración, experiencia, investigación narrativa, reflexión.

Teacher learning has been seen as an essential process that should be ongoing and lifelong. On this, “the process of becoming the best teacher one is able to be, is a process that can be started but never finished” (Underhill, 1999, p. 17). It could also be said that teachers are in need of pursuing change in their own professional skills and practices. Nonetheless, in this aforementioned interest in improving their own practices, teachers have moved away from instrumental practices and have become more interested in undertaking symbolic-interpretive epistemologies (Czarniawska, 1997) where experience is fundamental to understanding life as it is lived.

In the literature available, special attention has also been given to the reflection of teachers regarding their own classroom practices (Littlewood, 2011). Regarding this, Richards and Lockhart (1994) asserted that teachers make use of their own knowledge, training, and teacher experience to build up their own theories in order to improve their teaching practice. This might imply that experience has been, as well as reflection, positioned as knowledge for living (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000; Dewey, 1938). Importantly, this knowledge has concentrated specifically on how teachers construct their professional identities in ongoing interaction with other colleagues (Díaz-Maggioli, 2003), yet barely has it been used to collaborate and help others improve their teaching practice from a more reflective and personal lens.

Moreover, a depth of literature indicates that many English as foreign language (EFL) teachers have undertaken research as a way to inquire about their own practices and about their own identities as professionals. Conducting research has emerged then as a systematic way to dig into the classroom that seems to have made teachers claim that (a) research can work as a way to reduce teachers’ feelings of frustration in isolation (Roberts, 1993) and (b) it has the potential to allow teachers to be more reflective, critical, and analytical about their behaviors in the classroom (Atay, 2006). Despite these benefits, conducting research is not yet capturing the experiences and realities that both teachers and learners encounter and that may be the reason why some still remain skeptical and argue that teacher research is still not seen as practical inquiry (Hammersley, 2004).

In closing the aforementioned discussion, it has to be said that even though teacher research has been mainly carried out in isolation, there has not been much opportunity for teachers to interact with other teachers and learners and with their environment; there has been some acceptance regarding the idea that teachers consider opportunities to talk with other teachers as a means to reflect upon their discipline (Sandholtz, 2002). This interest in improving one’s own practice has opened up room to think of teaching as a reflective yet question oriented activity, which in essence puts forward the idea of “how to frame and then how to solve the question at hand” (Zeichner & Liston, 1996, p. 5).

Therefore, this article aims to report our experience (the researchers) in teaching vocabulary. However, the main purpose hereafter will be to document how we reflected upon our teaching to claim ownership of our own practice and in so doing improve students’ vocabulary learning. We want to make clear that this reflection embraces multiple ways of representing our lived experience discursively. This is why this study acknowledges that “all inquiry is narrative” (Hendry, 2010, p. 73) and then the inquiry process this study accounts for and elaborates on is the result of a process of asking questions to determine how to improve vocabulary teaching.

Narrative Inquiry: The Narrative Event

A narrative is understood as the primary way in which humans make meaning (Bakhtin, 1981; Bruner, 1986). In consequence, this study takes on narrative inquiry as research methodology to understand personal experiences regarding teaching. Since the term narrative has been imbued with a myriad of definitions, the study conceived narrative inquiry as described by Clandinin and Rosiek (2007) who state that narrative inquiry begins with “respect for ordinary lived experience’ as it explores both individuals’ experience as well as the social, cultural, and institutional narratives within which individuals’ experiences were constituted, shaped, expressed, and enacted” (p. 42). As such, any inquiry through narratives should take into consideration those personal, social, and cultural events that can shape the personal experience.

A narrative event would then refer to a meaningful or distinct event that has a pattern that emerges from others and that leads to changes within a defined period as well (Griffin, 1993). In this respect, such patterns in a narrative event are to be seen as “the stories a person constructs from memory about an experienced event” (Westby & Culatta, 2016, p. 261) when interacting with others. For Porter, Larson, Harthcock, and Nellis (2002), a narrative event leads to action since it is based on reflection; thus, a narrative event encapsulates temporal, chronological, and personal accounts of experience that, in this study, work as a mode of inquiry in which there are in fact multiple ways of coming to know our own teaching practice.

Having said this, this narrative study first, begins with an interest in experience (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000); second, proceeds from our own ontological position and a curiosity as EFL teachers to make sense of our own experience teaching vocabulary. Finally, the study concludes with the analysis of the discourse of our professional lives (Foucault, 1972) by understanding this discourse as our narratives.

Reflective Teaching

Teaching English is in essence a reflective endeavor. Zeichner and Liston (1996) argue that

Teaching from a reflective perspective is . . . the critical examination of experiences, knowledge and values, an understanding of the consequences of one’s teaching, the ability to provide heartfelt justifications for one’s beliefs and actions and a commitment to equality and respect for differences. (p. 48)

Amobi (2006) echoes this by seeing reflective teaching as a theory that generates the means for teachers to create their own theories. We might say then that the core of teaching reflection is embedded in the personal commitment of understanding one’s own practice.

Many have contended that reflection is an essential component of professional practice (Bradbury, Frost, Kilminster, & Zukas, 2010). Importantly, “reflection is typically understood as what allows us to learn from experiences either personal or impersonal by thinking back on them” (Khanmohammad & Eilaghi, 2017, p. 547). Then, reflective teaching, in this study, merges both the mechanism to reflect upon one’s knowledge regarding teaching that we will hereafter name as narrative events and one’s beliefs about teaching. These assumptions imply that “not only are we continually producing narratives to order and structure our life experiences, we are also constantly being bombarded with narratives from the social world we live in” (Moen, 2006, p. 62).

Vocabulary

Teaching vocabulary is part of teachers’ agenda in a class. Since “vocabulary is very important, to be sure, and requires a systematic approach in its own right” (Tosuncuoğlu, 2015, p. 4), this study sees vocabulary as “the knowledge of the meanings of words” (Hiebert & Kamil, 2005, p. 3). However, such a perspective is not intended to be a narrow approach to the concept of vocabulary learning; instead, it aims to present vocabulary as a cognitive task that includes the ability to use words automatically as well as the capacity to remember them in wider contexts (McCarthy, 1984).

Even though “when considering teaching vocabulary, perhaps one of the first dilemmas faced by teachers is what to teach” (Wallace, 2007, p. 189), there seems to be a well-known recognition of the fact that no matter what we choose to do, vocabulary is the most sizeable and unmanageable component in the learning of any language (Nation, 2001). Nonetheless, it is in that broad scope of complex instruction that, we believe, there is still room for innovation, for re-thinking vocabulary teaching.

This study took on narrative inquiry as both phenomenon and methodology (Clandinin & Connelly, 2000). Since this study presents a pedagogical intervention from where the analysis and reflections of our teacher practice emerged, the study also adopted Macintyre’s (2000, p. 10) model of action research in which planning, reflecting, and acting are the main stages to account for the pedagogical intervention regarding vocabulary teaching. This epistemological decision is grounded on the assumption that all inquiry is narrative and therefore narrative as one particular form of inquiry provides a critical space for merging the principles of action research and narrative as inquiry.

If we take into consideration that action research has the potential to change and empower teachers in their own teaching practice (Kemmis & McTaggart, 1988; McMahon, 1999), it seems to be valid merging it with narrative inquiry. Action research is an approach to “enhance the lives of professionals” (Mills, 2003, p. 10); then, this study sees action research as a process to change actions yet inform on experience (Kolb, 1984). Consequently, due to its reflexive, collaborative and interventionist nature (Cooke & Wolfram Cox, 2005), action research was chosen to bridge the gap between the pedagogical intervention we conducted in our classrooms and the narrative events we chose to report in this manuscript to make sense of our experience as teachers.

Context

The study was conducted in a private but non-profit English language teaching institution in Bogota, Colombia. It was carried out in an adult English program (AEP, hereafter). The program takes on the philosophy of teaching students to become better communicators. Therefore, teachers are to uphold and foster the creation of appropriate conditions for students to learn. This implies the necessity of placing students in the center of the process. Since the program prompts the growth of communicative teaching by incorporating elements of project-based and task-based learning, vocabulary, grammar, and other formal elements of the language are expected to be embedded within the usual teaching practices and learning routines of students.

Since learning is a continuous process (Kolb, 1984), the purpose of the study was to document how two EFL teachers (us) engaged in reflective teaching to claim ownership of their own practice and in so doing improve students’ vocabulary learning. To understand our teaching practice regarding vocabulary teaching, collaborative lesson plan meetings were held, recorded and transcribed to reveal our individual conceptions regarding vocabulary. In addition, class sessions were recorded, as were teachers’ insights about the classes where vocabulary was taught. Data were collected for a period of six months and ten collaborative sessions were recorded as well as twelve classes in which there were sixty students involved.

The purpose of the study was to look for specific narrative events where we could reveal traces of reflection upon our own teaching practice and therefore document how we were engaged in reflective teaching to claim ownership of our own practice. To do so, data analysis departed from the use of a thematic analysis of the transcripts in order to uncover a collection of themes, “some level of patterned response or meaning” (Braun & Clarke, 2006, p. 82) within a data-set. Consequently, data presented in this manuscript serve to reveal both the pedagogical component that has to do with vocabulary teaching in some pedagogical intervention stages (Macintyre, 2000) as well as the experiential component that emerged from our reflection and experience.

Stage 1: Planning - Collaborative Lesson Plan Meetings

From the collaborative lesson plan meetings, we started by mapping our own practices regarding vocabulary teaching. In so doing, we came to the realization that our vocabulary teaching practices followed two main trends in our classes. These were limited to either having students notice or repeat words in class.

Topic of reflection: How vocabulary has been taught

T1:1 I...I always have my students prepare the lesson. I mean, they check the lesson before class to see if they know the words and if not they just look for their meaning. In class, I sometimes ask for the pronunciation as well. For example, once I did something different with slides and games but that did not work, you know...maybe I was not that convincing.

T2: I know what you mean, I have done that too but in my case, I have them repeat those words they prepare but I tell them: “If you do not use them, you lose them”. [sic]

Interestingly, when we revised our practices under the light of some literature consulted, we noticed that these personal theories of teaching were to some extent echoing what Nation (2001) had already proposed regarding vocabulary teaching: Noticing may occur either “when learners look up a word in a dictionary, deliberately study a word, guess from context, or have a word explained to them” (p. 63). Repetition has more to do with the spacing of repetition in class (Nation, 2001). We could see that even though what we were doing was not consciously theory-based, our practices did have theoretical ground we were not aware of.

Our personal epistemological belief regarding what was effective or not when teaching vocabulary also emerged from discussing our practices. These beliefs were indeed to further delimit how to teach vocabulary, yet when we sat to explore our practices we could notice we had different conceptions regarding vocabulary teaching. The excerpt below can be used to understand this.

Topic of reflection: Conceptions of how vocabulary should be taught

T1: I... I think when I have my students prepare the class I know I cannot just do that, I mean...I know I should use more exercises for students to use those words in context but to be honest at times the lessons have so many expressions that it is hard to know which I should focus on the most. What I think word for real is when I have them speak and in way, I make them use the words.

T2: I know what you mean...but I know students like to be given games. I use some Apps. They use them and it triggers their attention.

T1: But do they use them? I mean the words.

T2: Sometimes, but they eventually do it. I think that works too. Besides, if they improve their speaking I think is because what I do works, no? and you know we have to teach what there is in the book. [sic]

These conceptions of how and why vocabulary should be taught were linked to effective learning (Brownlee, 2001) since what we were proposing was in essence personal pedagogies to approach the teaching of vocabulary. However, when transcribing this recording, we noticed that our arguments were, as well, acknowledging that language teachers and learners are faced with a rather narrow range of communicative contexts in the classroom, and classes are often limited to “discussion topics presented in language learning materials intended to reinforce previously introduced vocabulary and grammar lessons” (van Compernolle, 2010, p. 451).

Our negotiation of how to teach vocabulary effectively helped reveal some of the epistemological beliefs we held and that were a lens through which we were interpreting our own practice and the practice of the other. What really came out from these collaborative sessions was that since our personal epistemology or beliefs regarding teaching were not fixed but ongoing, we had the chance to modify them.

Topic of reflection: How vocabulary can be taught

T2: When students memorize vocabulary they do not use those words, I think it is because they just find it hard to know where they can use that, no?

T2: Yeah! Or at least they do not want to. But I think we can begin by revising what we have done, I mean...can I see the material you have used? You can see mine and see if we can make both work in one.

T1: OK, but mine are just copies!

T2: [Laughs] mine too, I have some games on some apps but I think once we can change that and see how we can improve that, we will see what works for real. [sic]

Since these ongoing and open to change one’s own theories of knowledge and knowing processes were to be linked to students and their processing of our teaching, we decided to act. However, as our teachers’ beliefs were constructed in the context of our experience, we needed to start with exploring one more time what we thought we knew.

Stage 2: Acting

Even though the previous stage of the study followed narrative inquiry to understand our own epistemologies regarding vocabulary teaching; Stage 2—acting—elaborates on the pedagogical intervention of the study. Then, when lesson planning collaboratively, we agreed on acknowledging that vocabulary was obviously an essential element within language. Therefore, we organized a pedagogical intervention that we broke into two main stages hereafter briefly reported.

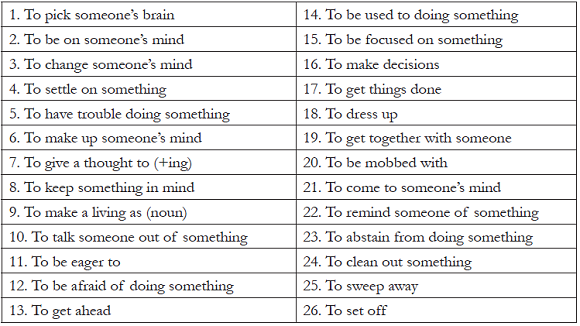

The diagnosis. After having explored personal pedagogies and epistemologies to approach the teaching of vocabulary, we decided to begin by diagnosing students’ knowledge of vocabulary. To do so, we compiled a set of frequent vocabulary words we expected to reinforce (see Table 1); these words were chosen due to the number of times they appear along the units of study. The aim was to explore how knowledgeable learners were regarding the vocabulary they were going to encounter. Regarding this, students were administered some pre-tests with some specific expressions taken from each unit to be covered along the course. The pre-tests aimed to expose students to vocabulary in order to gauge their lexical repertoire and their ability to make meaning out of expressions that were presented out of context and in isolation (see Appendix for a sample of the pre-test).

Table 1. List of Vocabulary to Be Learned

Nonetheless, not only were pre-tests used as a pedagogical mechanism to have students become aware of their own weaknesses regarding vocabulary, they were also used to understand the extent students were knowledgeable of the use of the words given. Inasmuch as students are to go from basic to upper-intermediate levels, they have shown a tendency to either make use of the same expressions when speaking or to show little abilities to incorporate the vocabulary previously learned into the new communicative situations. As far as this article is concerned, this tendency prevents students from moving forward in their process and attaining higher levels of proficiency.

Bearing the aforementioned in mind and after having collected and analyzed the information from the pre-tests administered to students, we came to the realization that the great majority of students had some knowledge in terms of the semantic use of the expressions. This knowledge had to do with the possibility of recognizing synonymous language that could state the same or similar meaning regarding the word provided.

As can be seen in Figure 1, most of the students tested exhibited understanding of the phrasal verb run into which is used in the upper-intermediate level studied. However, the fact most students had some prior knowledge in terms of vocabulary did not necessarily mean students would actually use it on a regular basis when engaging in communicative situations.

Figure 1. Knowledge of Vocabulary: Students’ Response to the Meaning of the Expression “To Run Into Someone”

However, the data shown in Figures 2 and 3 also make evident that some other students seemed to be unclear of the meaning of other words. They were either confusing meaning with synonymous language or just selecting any option at random. Then, out of these findings we confirmed that for learners to make the most of the vocabulary proposed for the learning process, it was necessary not only to set the scene to use the above vocabulary purposefully, but also to design a new pedagogical intervention to avoid blurring out the main communicative purpose of learning vocabulary in an EFL classroom.

Figure 2. Knowledge of Vocabulary: Students’ Response to the Meaning of the Expression “Discourteous”

Figure 3. Knowledge of Vocabulary: Students’ Response to the Meaning of the Expression “Unavoidable”

The intervention. After having gotten the results from the diagnosis stage, we directed our attention to the communicative events of our classes. In this respect, we took on a communicative event from Savignon’s (1983) notion of communicative competence:

It is a dynamic rather than a static concept . . . it depends on the negotiation of meaning . . . it applies to both written and spoken language as well as too many other symbolic systems . . . it is context-specific . . . it takes place in an infinite variety of situations . . . it is defined as a presumed underlying ability . . . it is relative, not absolute, and depends on the cooperation of all the participants involved. (pp. 8-9)

Thus, we directed attention to this moment of the class to explore how by exposing students to more communicative situations, they could integrate the new vocabulary and use it in a more purposeful way. This decision was made due to the lack of communicative events we used to provide students with. As presented in the diagnosis stage, we wanted to integrate other modes of learning and teaching vocabulary that were different from having students memorize or repeat words. To do so, we first decided to read some literature regarding the philosophy we were following in the language teaching institution where this study took place.

On this, we realized that the AEP revolved around task-based learning as the main teaching approach. This implies that language should be a communicative activity and not a system for the coding of meaning. Thus, having students memorize or repeat words was simply a very lexical-structural view of language we had to move away from. The excerpt below helps reveal a moment of reflection we set for this discussion.

Topic of reflection: Theories of language and learning

T1: I think we do not really know what we are following. I mean, we do many things, we assess, we elicit, we teach grammar inductively, and so on and forth but when I read the program’s philosophy, I saw I am not aware of what task-based learning is really about.

T2: I know, I remember this is about negotiation of meaning and stuff like that. So, what we do in classes has nothing of negotiation because, you know [hesitation] what negotiation is there in memorizing or repeating?

T1: [laughs] I know but anyway we can have students speak more about what they know. I mean the book is OK, we have to use it, but we can spice up classes a bit more. [sic]

Then, in accounting for this stage of intervention, we decided as well to audio record students’ interactions. We decided to do this inasmuch as any learning situation can be meaningful if (a) learners have a meaningful learning set—that is, a disposition to relate the new learning task to what they already know—and (b) the learning task itself is potentially meaningful to the students.

The transcription below is an excerpt of one of the interactions recorded. In this excerpt, students were to discuss some controversial issues in the local community. They decided to speak about prostitution.

S1: No offense, but I just can’t agree, why? because... eh no offense but I just can’t agree. Why? because in the downtown you can run into some prostitutes that does not use condom for example, are not like the prostitutes in the “piscina”, it’s just prostitutes related with sexual services for people, for people poor, really poor people homeless people things like that it is related with virus and control virus and I think we need to control that thing in some specific places, I think the real...could be a good way to improve our society and our life eh...quality I think, I think that’s all. [sic] (Unit 9. Communicative event, Controversial issues)

In the excerpt above, we could see this student was indeed using one the expressions taught. This was evidence for us that not only were students acquiring some vocabulary repertoire but they were also trying to adapt the meaning they had learned before to the new communicative situation. Then, even though “learning new words is often considered a very difficult task” (Gore, 2012, p. 29), we came to the realization that by having exposed students to more communicative tasks, new vocabulary could be used in a more meaningful and purposeful way if it is given to discuss something that is both familiar and interesting for them.

In the same communicative event we referenced above, we could also notice the other students’ reactions towards the discussion set in class, apart from the intervention of a third student who wanted to give a hand confirming the meaning of a word. We could also notice that not only were students trying to use the expressions required, but they were also contesting or resisting discourses that were being constructed at the moment of the conversation.

S1: I do not think it is easy for prostitutes to make a living in this way...eh no teacher is this okay?

S2: yeah, that is ganarse la vida (make a living) you know you make money in that way!

S1: OK, so as I was saying, you need to do something to survive and if you can live a good life working like them you just cannot say that prostitutes are the problem, I think you men who love sex are the ones who want to pay so you have to think first. [sic] (Unit 9, Communicative event, Controversial issues)

Stage 3: Reflecting on Outcomes

Since reflection is claimed to improve learning, we realized that reflection upon what students did in class was also pivotal to understanding how vocabulary was learned. In this respect, we began exploring data from the classes recorded and the lesson plans we had previously created. We found out that students seemed to use the vocabulary of the class when exercises were monitored by teachers and, as a result, seemed to be eager to find possible synonyms or similar expressions. However, we also noticed that the personal discourses regarding social realities emerged and those discourses made students work individually to structure ideas in a different way.

Topic of reflection: Use of vocabulary

T1: I saw they used some words. Some of them tried, you know...but I still feel they do not get it. I mean, some of them do great but others, I am not sure but in general, I think that if we have them speak more at some point they will use those words properly. I like the fact they notice they speak better. I ask them: “how do you feel using the new words?” And they say things like: “better teacher, I know more ways to express the same idea not that basic.”

T2: Yes, mine also say that but I noticed they feel challenged. You set the criteria for the activity and tell them they have to use new expressions. They stress out at the beginning but end up doing well. You know...in the assessment I have them repeat the pronunciation if they make a mistake but now I think it is more communicative.

T1: you know what, I think they also say what they think. I know they used the expressions that was great but didn’t you see they were very passionate in the discussions? [sic]

Interestingly, this process allowed us to think we needed to re-orient activities designed to help students take their first step to initiate their “self-directed” learning process. Regarding this, we took on self-directed learning as the individual learner capacity and maturing ability to reflect upon, set goals for, make decisions in regard to, and take responsibility for her/his own learning over time (Knowles, 1975). Therefore, within this new orientation, we had to conceive the idea of not just looking at vocabulary from the instrumental lens we took it on from the beginning of the study, but as something more multidimensional and socially constructed that could include students’ own voices and ideas.

Through lesson planning, it was possible to put together different activities and classroom perspectives. Then, planning served to establish a road map to put individual epistemological beliefs into a more collaborative perspective. In this respect and grounding this on the reflective perspective the study took on, we would like to acknowledge first, that action research is indeed a vehicle for personal and professional development (Burns, 1999) yet, it can only be a possibility for professional development if it explores our own realities as teachers with the aim of encouraging us to learn from our practice.

Secondly, those continuous processes of sharing one another’s efforts to sort out problems in the classrooms led to construct better professional scenarios in order to interact as professionals. Then, if we take into consideration that inquiry “tells us about something unexpected” (Bruner, 1996, p. 121), we manage to put our life experiences in narrative form to claim that it is through narratives that we can find those hidden but multiple ways of coming to know. Consequently, we want to acknowledge that even though knowledge is indeed constructed through social interactions, including daily conversations, discussions, and negotiation processes (Luria, 1976; Rondon-Pari, 2011), it requires collaboration as the core principle for professional development. Learning is only possible through teaching and through a process of reflection, self-monitoring, and self-evaluation (Roberts, 1998). With this, we do not mean that self-reflection does not produce knowledge, but what we do want to contend is that when it comes to professional development, collaboration becomes the driving force to adapt teaching to get better learning outcomes.

Pedagogically speaking, conducting action research as a collaborative endeavor turned out to be paramount to “transform the educational practice into a meaningful pedagogical process” (Kapachtsi & Kakana, 2010, p. 44). Research served to develop a deeper understanding of our practice. Through action research, we framed our own questions, interests, and inquiries into a strong reflective component and method to document and enhance what we knew in terms of vocabulary instruction. We reflected upon personal conceptions and experiences regarding the matters of vocabulary teaching and learning. By doing so, we came to the realization that successful vocabulary practices go hand in hand with the pedagogical resources and teaching tools the teacher uses inside the EFL classroom.

Vocabulary, as well as other components of the language, is pivotal for the development of effective communicative moments. As such, it needs to be presented from multiple perspectives and approaches that permit the integration of other language skills. Moreover, if self-directed learning is defined as “a process in which individuals take the initiative, with or without the help of others, in diagnosing their learning needs, formulating learning goals, identifying human and material resources for learning, choosing and implementing learning strategies, and evaluating learning outcomes” (Knowles, 1975, p. 18); vocabulary teaching practices, then, must engage students in self-directed learning routines to allow them to deal with the communicative demands of the class. As such, vocabulary would definitely improve since a word learned in a meaningful context would be best assimilated and remembered (Schmitt & McCarthy, 1997).

In closing, there seems to be room for teachers to continue exploring vocabulary teaching from a more experiential lens. If learning is indeed a process and not an outcome, exploring teachers’ narratives regarding their teaching practices would become relevant to continue mapping teachers’ processes of learning. However, this sort of exploration would be done from the reflective lens needed in the process of critically examining practices and in turn having a better vision of one’s own teaching practices (Richards & Lockhart, 1994) in the classroom.

1T1 and T2 are used for the two teachers whose narratives are being examined. Students’ interventions are coded with an S followed by a number.

Amobi, F. A. (2006). Beyond the call: Preserving reflection in the preparation of “highly qualified” teachers. Teacher Education Quarterly, 33(2), 23-35.

Atay, D. (2006). Teachers’ professional development: Partnerships in research. TESL-EJ, 10(2), 1-14.

Bakhtin, M. M. (1981). The dialogic imagination: Four essays. Austin, US: University of Texas Press.

Bradbury, H., Frost, N., Kilminster, S., & Zukas, M. (2010). Beyond reflective practice: New approaches to professional lifelong learning. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

Brownlee, J. (2001). Knowing and learning in teacher education: A theoretical framework of core and peripheral epistemological beliefs. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education & Development, 4(1), 131-155.

Bruner, J. (1986). Actual minds, possible worlds. Cambridge, US: Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. (1996). The culture of education. Cambridge, US: Harvard University Press.

Burns, A. (1999). Collaborative action research for English language teachers. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Clandinin, D. J., & Connelly, F. M. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research. San Francisco, US: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Clandinin, D. J., & Rosiek, J. (2007). Mapping a landscape of narrative inquiry: Borderland spaces and tensions. In D. J. Clandinin (Ed.), Handbook of narrative inquiry: Mapping a methodology (pp. 35-75). Thousand Oaks, US: Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452226552.

Cooke, B., & Wolfram Cox, J. (2005). Fundamentals of action research. London, UK: Sage.

Czarniawska, B. (1997). Narrating the organization: Dramas of institutional identity. Chicago, US: University of Chicago Press.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. New York, US: Collier Books.

Díaz-Maggioli, G. (2003). Fulfilling the promise of professional development. IATEFL Issues, 4-5.

Foucault, M. (1972). The archaeology of knowledge. London, UK: Routledge.

Gore, V. G. (2012). Vocabulary conundrum: A practical approach. IUP Journal of Soft Skills, 6(3), 28-37.

Griffin, L. J. (1993). Narrative, event-structure analysis, and causal interpretation in historical sociology. American Journal of Sociology, 98(5), 1094-1133. https://doi.org/10.1086/230140.

Hammersley, M. (2004). Action research: A contradiction in terms? Oxford Review of Education, 30(2), 165-181. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305498042000215502.

Hendry, P. M. (2010). Narrative as inquiry. The Journal of Educational Research, 103(2), 72-80. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220670903323354.

Hiebert, E. H., & Kamil, M. L. (Eds.). (2005). Teaching and learning vocabulary: Bringing research to practice. Mahwah, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Kapachtsi, V., & Kakana, D. M. (2010). Cooperative action research as a model of educator professional development. Action Researcher in Education, (1), 40-52.

Kemmis, S., & McTaggart, R. (1988). The action research planner. Victoria, AU: Deakin University Press.

Khanmohammad, H., & Eilaghi, A. (2017). The effect of self-reflective journaling on long-term self-efficacy of EFL student teachers. In J. Vopava, V. Douda, R. Kratochvil, & M. Konecki (Eds.), Proceedings of AC 2017 (pp. 547-561). Prague, CZ: MAC Prague Consulting.

Knowles, M. S. (1975). Self-directed learning: A guide for learners and teachers. Englewood Cliffs, US: Prentice Hall/Cambridge.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, US: Prentice-Hall.

Littlewood, S. (2011). Transforming the practice of student teachers in the UAE through action research. Education, Business and Society: Contemporary Middle Eastern Issues, 4(2), 97-105. https://doi.org/10.1108/17537981111143828.

Luria, A. R. (1976). Cognitive development: Its cultural and social foundations. Cambridge, US: Harvard University Press.

Macintyre, C. (2000). The art of action research in the classroom. London, UK: David Fulton.

McCarthy, M. J. (1984). A new look at vocabulary in EFL. Applied Linguistics, 5(1), 12-22. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/5.1.12.

McMahon, T. (1999). Is reflective practice synonymous with action research? Educational Action Research, 7(1), 163-169. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650799900200080.

Mills, G. E. (2003). Action research: A guide for the teacher researcher. Upper Saddle River, US: Pearson Education.

Moen, T. (2006). Reflections on the narrative research approach. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(4), 56-69. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500405.

Nation, I. S. P. (2001). Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139524759.

Porter, M. J., Larson, D. L., Harthcock, A., & Nellis, K. B. (2002). Re (de)fining narrative events. Journal of Popular Film and Television, 30(1), 23-30. https://doi.org/10.1080/01956050209605556.

Richards, J. C., & Lockhart, C. (1994). Reflective teaching in second language classrooms. New York, US: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667169.

Roberts, J. R. (1993). Evaluating the impact of teacher research. System, 21(1), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1016/0346-251X(93)90003-Y.

Roberts, J. (1998). Language teaching education. London, UK: Arnold.

Rondon-Pari, G. (2011). Comparative analysis of classroom speech in upper level Spanish college courses: A social constructivist view. Contemporary Issues in Education Research, 4(12), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.19030/cier.v4i12.6664.

Sandholtz, J. (2002). In service training or professional development: Contrasting opportunities in a school/university partnership. Teaching & Teacher Education, 18(7), 815-830. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(02)00045-8.

Savignon, S. J. (1983). Communicative competence: Theory and classroom practice. Boston, US: Addison Wesley.

Schmitt, N., & McCarthy, M. (Eds.). (1997). Vocabulary: Description, acquisition and pedagogy. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Tosuncuoğlu, İ. (2015). Teaching vocabulary through sentences. Journal of History, Culture & Art Research, 4(4), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.7596/taksad.v4i4.501.

Underhill, A. (1999). Continuous professional development. IATEFL Issues, 149.

van Compernolle, R. A. (2010). Towards a sociolinguistically responsive pedagogy: Teaching second-person address forms in French. Canadian Modern Language Review, 66(3), 445-463. https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.66.3.445.

Wallace, C. (2007). Vocabulary: The key to teaching English language learners to read. Reading Improvement, 44(4), 189-193.

Westby, C., & Culatta, B. (2016). Telling tales: Personal event narratives and life stories. Language, Speech & Hearing Services in Schools, 47(4), 260-282. https://doi.org/10.1044/2016_LSHSS-15-0073.

Zeichner, K. M., & Liston, D. P. (1996). Reflective teaching. Mahwah, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

The Authors

Diego F. Ubaque works for the Centro Cultural Colombo Americano and Pontificia Universidad Javeriana (Colombia) as an EFL teacher. He holds an MA in applied linguistics to the teaching of English from Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas (Colombia).

Fredy Pinilla works for the Centro Cultural Colombo Americano (Bogotá) as an EFL teacher. He holds a Bachelor’s degree in education from the University of South Carolina (USA). His research interests have to do with assessment practices in the EFL classroom.

Unit 2: Health Matters, Task Sk4

Name:

Date:

Pre-testing exercise II

Read the words below. You are to choose the one word or phrase that best keeps the meaning of the original one. Make sure to circle the one you consider may the best option.

1. To be wondering

2. To fit someone in

3. To bring in

4. To bother

5. To have a look at something