https://doi.org/10.19183/how.25.2.406

Alexandra Novozheninaa

Margarita M. López Pinzónb

aCentro Colombo Americano, Manizales, Colombia. E-mail: Alexandra.novozhenina@colombomanizales.com

bUniversidad de Caldas, Manizales, Colombia. E-mail: margarita.lopez@ucaldas.edu.co

Received: September 5, 2017. Accepted: February 13, 2018.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Novozhenina, A., & López Pinzón, M. M. (2018). Impact of a professional development program on EFL teachers’ performance. HOW, 25(2), 113-128. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.25.2.406.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. License Deed can be consulted at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This article gives an account of a project aimed at improving the teaching practice and self-reflection of English as a foreign language teachers in Manizales (Colombia) by means of a professional development program. At the initial stage, surveys, class observations, and documentary analysis allowed the researchers to identify teachers’ professional needs, as well as the areas that needed improvement. During the action stage, class observations, informal chats, and a survey were used in order to reveal the impact of the professional development program. Findings demonstrated that although the program initiated some slight changes in teachers’ performance and reflection, it still left space for more training and improvement.

Key words: Teacher performance, teacher professional development, teacher self-reflection, teacher training.

Este artículo trata sobre un proyecto que tuvo como objetivo mejorar la enseñanza y reflexión de profesores de inglés en Manizales (Colombia) por medio de un programa de desarrollo profesional. Durante la etapa diagnostica se realizaron encuestas, observaciones de clase y análisis documental, que permitieron identificar las necesidades profesionales de los docentes y sus áreas a mejorar. Durante la etapa de acción, se implementaron observaciones de clase, charlas informales y una encuesta con el propósito de medir el impacto del programa de desarrollo profesional. Los hallazgos mostraron que, aunque el programa conllevó a unos cambios leves en el desempeño y reflexión de los docentes, todavía quedaron varios aspectos por mejorar.

Palabras clave: auto reflexión, desarrollo profesional, desempeño docente.

The topic of professional development is frequently underestimated both by the administration of the institutions and by teachers themselves in Colombia. It happens due to various reasons. As a rule, a lot of attention is paid to the level of English and the qualifications the teachers have, and as long as they comply with these two requirements, their profile is considered good enough to be given the position. As a consequence, teachers might become less interested in improving their practice and feel no need to continue their professional development. Apart from that, it is common to find teachers who are overloaded with work and taking into account the fact that the teaching profession implies not only class hours, but also a lot of extra work (planning, grading, etc.), it is understandable why teachers have no time left for updating their knowledge.

Nevertheless, lack of continuing professional development may result in serious issues. First of all, it is a fact that the modern world is changing rapidly; therefore, what students learn at the university may become outdated by the time they graduate from it, and some professions that will be highly demanded in ten years might not even exist now. Second, “labeling teachers as ‘highly qualified’ . . . does not in fact make them highly qualified” (Loeb, 2008, p. 1). Moreover, there may be serious consequences when teachers believe that their methodology is the most appropriate while it might be, in fact, outdated. For example, in a study conducted among public school teachers in Cali, Colombia, it was discovered that some teachers still considered the grammar approach as the best way to teach English as a foreign language (EFL). In addition, they “had difficulties when assimilating the information on new trends like CLIL and TBL” (Chaves & Guapacha, 2014, p. 164). Therefore, it becomes obvious that in order to keep up with the modern pace, teachers need to be continuously learning new things, polishing and adjusting their skills according to the needs of the world. Professional development thus becomes the bridge that will connect the point where they are now to the point where they need to be.

Continuing professional development becomes the key to effective teaching and thus a way to progress in the teaching-learning process. This article presents a reflection on a study in which a professional development program (PDP) took place and attempted to improve teachers’ performance by encouraging them to reflect on their practice. Apart from the results obtained after the intervention, some findings allowed us to make conclusions about the differences in the ways that professional development takes place for novice and experienced teachers. How do in-service teachers with different experience and background respond to interference in their teaching process? How does improvement take place? At what point do they start reflecting? These are some of the questions that inspired our curiosity during the research project.

When reviewing the literature for the present project, we had to comply with two tasks. First of all, to cover the literature devoted to the methodology in order to be able to prepare the content of the PDP correctly. Second, to scrutinize articles and books related to the topic of teacher professional development so as to design the program properly. In this chapter, we present the results of the careful literature examination.

Teacher Quality

It has always been difficult to define the qualities that constitute a qualified teacher. As a matter of fact, the term has been “a common concern in daily life, in education policies, and in academic literature” (Chaves & Guapacha, 2014, p. 8). First of all, the concept changes depending on different contexts: for instance, one would not expect a university professor and a first-grade teacher to share exactly the same characteristics. Second, there are so many details to be included in the description that it might seem quite difficult to embrace them all. In addition, each person, just like each student, can have a different idea of what “a good teacher” means.

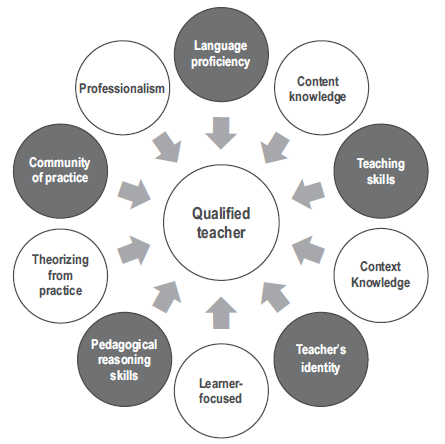

Richards (2010) made an attempt to unite all the characteristics of a “good teacher”, and as a result, he came up with ten characteristics that define a qualified teacher (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The “Qualified Teacher” Concept (Richards, 2010)

Nevertheless, even the author admits that his description will not apply everywhere by saying that it grasps the notion of a good teacher from the point of view of “western orientation and understanding of teaching (Richards, 2010). One can notice that his idea of a good teacher is quite wide and includes a lot of various features; therefore, it might take teachers several years to possess all of them which may seem to be quite challenging.

At the same time, some other experts define teacher quality in a less complex way. For instance, Kunter et al. (2013) write about professional competence and say that it includes “the skills, knowledge, attitudes, and motivational variables that form the basis for mastery of specific situations” (p. 3). This perspective is somewhat different from Connelly, Clandinin, and He’s (1997) viewpoint which refers to knowledge in action rather than to passive knowledge. According to them, this is “what teachers know and how their knowing is expressed in teaching” (Connelly et al., 1997, p. 665).

Teacher Professional Development

“An education system is only as good as its teachers,” (UNESCO, 2015, p. 4). This means that anyone interested in having a successful system of education ought to look for ways in which teachers can become better educators, which brings us to the topic of teacher professional development. First of all, it is important to define the term. According to Glatthorn (1995), professional development can be seen as “a result of gaining increased experience and examining his or her teaching systematially” (p. 41). This definition encompasses two essential aspects of teachers’ professional growth: first, the need of learning through experience rather than from mere memorization of literature, and second, the importance of reflecting about one’s own performance. On the other hand, Freeman (1989) placed reflection much higher than teaching practice stating that a change can happen due to “increasing or shifting awareness” (p. 40). However, the definition proposed by Day (1999) includes several aspects and adds emotional intelligence as an essential component that should be developed in an educator.

Whichever definition one agrees with, there are always numerous reasons why teachers should engage in professional development. The first and most obvious reason is the fact that good teaching results in good learning. “In education, research has shown that teaching quality and school leadership are the most important factors in raising student achievement” (Mizell, 2010). Without a doubt, the improvement in teachers’ day-to-day practices will result in better learning by their students. Murray (2010) also adds empowerment to the list. According to her, it can encourage teachers to become more involved in the teaching-learning processes that take place at their institutions and thus contribute to the overall improvement. Furthermore, Murray also adds that professional development helps teachers overcome their isolation and, as a consequence, share and get rid of any possible frustration they might experience due to some issues they face in their classroom.

Professional development may take various forms, and the best one should be found by each institution individually based on many factors, such as context, background, and needs (Diaz-Maggioli, 2004). In general, all the different types of professional development can be divided into two big groups: “organizational partnership models” and “small group or individual models” (Villegas-Reimers, 2003, p. 70). The former implies certain institutional support and, as a rule, takes the form of a life-long professional development that guides teachers throughout their career. Moreover, it frequently includes partnerships between institutions and universities that provide support in teacher education. As for the latter, that group includes more personalized ways of professional development, for instance, classroom observation, teaching conferences, case studies, and so on.

When designing a PDP, “it is important that educators create a space where they contribute to decision-making and have a voice” (Rodríguez Bonces, 2014, p. 310). First, they might have a different opinion regarding the needs that they have. Second, the more involved teachers are in the design of a PDP, the higher responsibility they will take for their own learning.

Finally, something that should also be taken into account when planning is teachers’ individual characteristics (Diaz-Maggioli, 2004). In other words, teachers’ learning should be personalized according to their background, experience, and career stage at which they find themselves at the moment. If this is taken into consideration, teachers might feel much more satisfaction from their own development and consider it much more useful and productive.

Reflecting on Teaching Practices

Improving teaching practice requires a lot of effort, patience, and persistence. However, apart from that, it also requires an inner trigger that can initiate change, and that trigger is reflection. According to numerous experts, reflection is an essential element, a “vital factor” (Saylag, 2012, p. 3851) in teachers’ development processes. Due to the fact that “personal beliefs and reflections on . . . professional development inform . . . pedagogical choices” (Saylag, 2012, p. 3851), it becomes of paramount importance to ensure that teachers’ reflective process goes in the right direction. Moreover, reflecting on their own practice helps teachers to become more autonomous and capable of developing on their own.

Another important reason to reflect is the fact that “without more time spent focusing on or discussing what has happened, we may tend to jump to conclusions about why things are happening” (Tice, 2004). Unless one clearly understands why certain events do or do not take place in one’s classroom, one cannot shape further classes accordingly in an efficient and productive way. Reflection thus becomes the bridge that connects practice to theory and that formulates our future actions.

The worldview proposed in this study was pragmatic; as a result, the approach used was mixed methods due to the fact that it incorporated parts of both qualitative and quantitative approaches. The approach was also selected because, according to Creswell (2014), it gives a more complete picture of the problem that is being analyzed.

Qualitative methodology was applied in the current work due to the fact that we were focused on exploring and understanding how various teaching strategies worked. Apart from that, the study was conducted in the participants’ setting (classroom) which is essential for qualitative research.

Quantitative methodology was implemented in many of the instruments used during all the three stages of the research. It helped to “build in protections against bias” (Creswell, 2014, p. 4) and thus make the study more objective.

We used the model of action research. Since one of the main focuses was analyzing how teachers applied theoretical concepts in practice, action research was very appropriate due to the fact that it bridges the gap between theoretical ideas that teachers learn in teacher training and professional development courses and what they need to do in their own classroom contexts with their colleagues and students (Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, 2007).

Participants

There were 35 in-service teachers. Twenty-five of them were experienced with more than five years of experience. It is also important to highlight that all the teachers at the institution where the study took place either hold a BA degree or have completed an English teaching course, such as TEFL, TESOL, among others. Although the teachers mentioned above were the main participants due to the fact that they took part in all the stages of the present research, there was also a group of students that took part only in the diagnostic stage with the purpose of identifying institutional needs.

Data Collection Methods

Four instruments were used in the diagnostic stage to collect data. First of all, a class observation journal was used in order to record how teachers applied their knowledge in practice and how they dealt with issues that arose in their classrooms. Second, a teachers’ survey was implemented to identify problematic teaching areas, weaknesses, and willingness to participate in a professional development program. Third, a students’ survey was conducted in order to find out what they thought about the learning and teaching process in the program, as well as its strengths and weaknesses. Finally, a documentary analysis was carried out, where several lesson plans were examined in order to detect teachers’ strengths and weaknesses in lesson planning.

During the action and evaluation stage, several other instruments were applied. Class observation checklists (internal and external observer) were aimed at identifying how well teachers could apply the new knowledge that they received during the workshops in their classrooms. Lesson plan analysis was used in order to find out if the teachers were putting into practice the knowledge they obtained during the workshop. A teacher questionnaire, which was administered after each class observation, intended to learn about the participants’ opinion about their own performance, as well as the effectiveness of the workshops. Finally, we applied a survey to find out what the teachers felt towards the program, and suggestions that could help improve it.

Diagnostic Stage

After all of the instruments were applied, data triangulation was performed in order to identify what issues turned out to be the most problematic. During the analysis, we used the grounded approach to find categories and codes as the data were analyzed. Figure 2 provides information about the categories encountered and their main issues.

Figure 2. Issues Identified During the Diagnostic Stage

Action Stage

When designing the action stage, two main aspects were taken into account: the topics to be covered in the PDP and the activities.

Defining the topics of the PDP. The topics were defined according to the results of the diagnostic stage. In total, ten workshops were designed and six implemented. They are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Action Stage Outline

Defining the design of the PDP. Due to the fact that all the participants were in-service teachers, they were most likely to have studied the topics mentioned above. Therefore, the objective of the program was to revive the theory and put it into practice. The workshops were designed taking into account the structure suggested by Diaz-Maggioli (2004). Figure 3 shows the steps followed in the design:

Figure 3. Workshop Design (Diaz-Maggioli, 2004)

Evaluation Stage

As for the evaluation stage, different instruments were implemented to evaluate the effectiveness of the topics introduced in the program. There were three classroom observations after each workshop; in each of them, we used a checklist that included topics covered in the corresponding workshop. Furthermore, there were informal chats with the participants which were complemented with questionnaires in order to analyze their opinions about their own development. In addition to that, there was an external observer who observed some classes at the end of the PDP and thus contributed with a different perspective on the overall effect of the program. Finally, the teachers filled out a questionnaire at the end of the program in which they expressed their impressions.

Having collected and analyzed all the data, we obtained the results summarized in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Evaluation Stage Results

After triangulating the action and evaluation stage, the following categories appeared:

Positive Results

Application of the new knowledge by teachers. Teachers demonstrated that they started to apply the concepts they had learned in their classroom. Some of them followed the strategies that they were taught in the course of the program such as the right lesson sequences, stages of the grammar lessons, and classroom management. As stated by Villegas-Reimers (2003), this is one of the most important results of a PDP because one of its main objectives should be “enhancing teaching effectiveness” (p. 67).

Positive learning effect from the PDP/Usefulness of the PDP.“Individual satisfaction”, as mentioned by Villegas-Reimers (2003, p. 19), is a very important aspect that should derive from a PDP. As a result of the current study, teachers expressed quite positive opinions towards the program in general. They stated that they had learned new things and that the program was useful for their daily practice. Furthermore, the participants made very positive comments in the questionnaire which showed that they enjoyed the workshops, learned from them and, on the whole, were satisfied with the results of the PDP: “I found useful everything but especially the workshop about error correction” (Participant). Apart from that, they had the same impressions during the informal chats—except for a single occasion in which a teacher stated that he had not learnt much due to his rich experience.

Some excerpts taken from the questionnaires reflect teachers’ positive reaction:

Teachers’ reflective approach. Many authors agree that reflection is a crucial skill for teachers (Clarke, 1995; Potter & Badiali, 2001; Zeichner & Tabachnik, 2001). If teachers are to become reflective, they need to “pay attention to daily routine and events . . . and to reflect on their meaning and effectiveness” (Villegas-Reimers, 2003, p. 104). After analyzing the results of the study, it can be concluded that some of the teachers improved a little in terms of reflection. After attending each workshop, they were aware of the fact that they still needed to improve and develop their skills, and they also understood that simply attending a workshop was not enough. Some examples of the teachers’ opinions are the following: “I became aware of things I didn’t notice before like making corrections and verifying if students understand the correction”; “we need to learn more about that topic.”

Results in Need of Improvement

Lack of application of the new knowledge by teachers. On many occasions, teachers showed a lack of ability to turn the theory into practice. For instance, they were not always able to implement strategies that dealt with error correction, teacher and student talking time, teaching writing and listening. Furthermore, the class observations (both by the researchers and the external observer) revealed the fact that the teachers did not apply the concepts, strategies, and techniques that were presented in the course of the program to the full extent. Therefore, despite teachers’ positive perception of their own performance, they still lacked the ability to connect theory and practice which would allow them to implement the knowledge they acquired in the program to their daily practice. A good example here might be the topic of error correction: During the class observations, we noticed that teacher correction still prevailed and that very few error correction techniques were actually implemented.

Moreover, in one of the class observations, a teacher inquired whether she had to apply the sequence that she was taught during the workshop (pre, while, and post activities for a listening exercise) and then admitted it was the first time she had used it since the workshop. According to Knowles (1973), “continuity” is an important concept in the theory of adult teaching. Therefore, effective teaching is not shaped as a result of occasional applications of a certain technique but rather “builds up experiences that are worth while” (Knowles, 1973, p. 72). The above-described case with the teacher clearly showed that she still lacked the ability to see the connection between theory and practice and the need to continuously follow the strategies that have been developed by EFL experts throughout decades of research.

No new theory in the PDP. A few teachers (6%) admitted that they did not learn new things during the development of the program, stating that they had vast experience in the field. However, the majority of the participants had an open-minded approach towards their own teaching that let them accept new ideas. This finding may speak in favor of many experts’ opinions that professional development should be personalized. Various reasons may cause that; however, the one that is mentioned more frequently is the fact that at different stages of their careers teachers may have different learning needs (Eros, 2011).

Lack of teachers’ reflective approach. This aspect is probably one of the most important ones. In his theory of andragogy, Knowles (1973) stated four assumptions that should characterize adult learning which teacher education certainly is part of. Two of them relate to the ability to reflect: “changes in self-concept” and “orientation to learning” (Knowles, 1973, p. 12). Therefore, teachers’ reflection is of paramount importance as it leads to further improvement of their performance. In the present research, some teachers demonstrated that they had a lot to improve regarding reflection. A good example here could be a teacher who said that he had never really thought about whether his listening activities were effective and productive for his students. Some of the participants did not seem to think much about the results and the effect that their lessons had. Although the teachers did demonstrate some reflection during the evaluation stage, we believe that the number of times they did it (a total of eight in all the instruments applied) was insufficient.

First of all, the cases in which the participants demonstrated reflection on their teaching practice are less frequent than one would expect from in-service teachers. In addition, occasional resistance to reflect also advocates for the fact that the participants have to continue improving on that aspect. For example, one participant stated that he “had already seen it all” and thus did not need to worry about improving any longer. Moreover, teachers were often not very objective when talking about their own classes; therefore, they still need to improve on their ability to self-assess.

Teachers always represent the educational institution where they are working. Therefore, they have to be aware of their own growth and professional development, experiment with new strategies that can help them improve and always have spaces to challenge their skills. As stated by UNESCO (1990), “because the teacher is the linchpin in the system of education, teacher preparation should be of paramount concern in any society” (p. 65). The conclusions of the present study are illustrated below.

Academic Aspects of a PDP

It is important to begin by stating that a PDP that consists of a series of workshops definitely impacts teachers and their knowledge. Nevertheless, that impact is rather theoretical than practical. It helps teachers to learn/refresh their fundamental knowledge but does not necessarily result in considerable changes in their practice. However, it is crucial to highlight that the most important factor that has to be worked on is not only teachers’ knowledge but also their ability to express, or apply, that knowledge when teaching (Connelly et al., 1997). Thus, the transition of the knowledge from theory to practice becomes the key goal. Although teachers do somewhat demonstrate improvement by applying what they learned in practice, they do so only 50% of the time; unfortunately, the rest of the time they tend to fail to successfully implement the right pedagogical strategies. Apart from that, training sessions on their own do not help teachers to become reflective and capable of looking at their performance objectively. They still perceive their skills in a very positive way, while, in fact, they might need to work more on some of them.

Furthermore, it is also essential to understand that professional development is an ongoing and endless process that develops throughout teachers’ whole career. According to Yates (2007), “their continuing education and training is . . . central to the achievement of quality learning” (p. 2). Therefore, improvement may take place continuously and little by little, and one of the things that can accelerate the process is reflection, which every teacher should develop. In that way, they could become more aware of their own learning and of the gaps they need to fill. Furthermore, institutions should look for different alternatives for professional development and never be limited to the format of workshops due to the fact that they may not lead to the desired results.

Teachers’ Role in a PDP

Pajares (1992) affirms that “attention to the beliefs of teachers and teacher candidates should be a focus of educational research and can inform educational practice” (p. 307). Hence, when an institution plans a PDP, teachers’ voices should play a very important role. First of all, their opinions may help to define the topics that have to be dealt with. Furthermore, they can help to shape the design of a PDP by expressing their needs and preferences regarding the various forms that it can take; the more comfortable they feel with the training format, the better the results can be. Finally, the fact that teachers play an active role in their own learning leads to the greater responsibility they take for it and, therefore, it helps them to grow as professionals.

The Design of a PDP

One of the major considerations that should be kept in mind when designing a PDP is the fact that “most professional-development initiatives use a combination of models simultaneously, and the combinations may vary from setting to setting” (Villegas-Reimers, 2003, p. 69). Hence, any PDP should be built by each institution individually and by taking into account several factors. One of them, as previously mentioned, should be the teachers’ voices. However, not only teachers, but also the direction/administration ought to express their opinion that can come both from classroom observations and from the needs of the institution.

In addition, when coordinators design a PDP, they should plan for several sessions per topic. Knowles (1973) writes that repetition and reinforcement are essential for learning. Indeed, as a rule, it appears that one training session is not enough for teachers to grasp the whole scope of an issue, thus it may turn out to be not as effective and productive as expected. Furthermore, relying on workshops only might not be sufficient for improvement to take place. Without a doubt, they do help teachers to learn; nevertheless, a format of a workshop might not always allow for much reflection or practical application. Of course, one may say that micro-teaching sessions could be held in order to help teachers learn to apply new concepts in practice; however, micro-teaching represents a sort of “green-house” condition that might be far from the real setting—just like classroom practice of a language for students is not the same as real language use outside the classroom walls.

In the fifteen different country overview of teacher professional development made by UNESCO (1990), it was affirmed that “growth experiences for teacher should be individualized” (p. 58). That being the case, it can be stated that professional development must be more personalized due to the fact that teachers are often at different stages of their careers. Even though they can be working at the same institution, their perceptions can be extremely different. Furthermore, it is possible that young teachers might find certain workshops extremely useful while more experienced teachers may feel bored with topics they already know, and vice versa.

To summarize, it is important to bear in mind that designing a PDP is an extremely complex task that implies a lot of details to be taken into account. Yet, it is also rewarding as it “enables the teachers to keep pace with new trends in education” (UNESCO, 1990, p. 9). The people who plan it should be very familiar with the institution, the context, with the teachers, their needs and styles, and should always remember that this process “extends throughout an individual’s career” (UNESCO, 1990, p. 58). A PDP should include a variety of techniques that would allow for different kinds of participation, as well as for a variety of interaction forms: both group and individual activities.

Chaves, O., & Guapacha, M. E. (2014). Impact of a professional development program on the teaching of public schools English teachers in Cali. Manizales, CO.

Clarke, A. (1995). Professional development in practicum settings: Reflective practice under scrutiny. Teacher and Teacher Education, 11(3), 243-261. https://doi.org/10.1016/0742-051X(94)00028-5.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2007). Research methods in education. Oxon, UK: Routledge.

Connelly, F. M., Clandinin D. J., & He, M. F. (1997). Teachers’ personal practical knowledge on the professional knowledge landscape. Teaching and Teacher Education, 13(7), 665-674. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(97)00014-0.

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. Thousand Oaks, US: Sage Publications.

Day, C. (1999). Developing teachers: The challenges of lifelong learning. London, UK: Falmer Press.

Diaz-Maggioli, G. (2004). Teacher-centered professional development. Alexandria, US: ASCD.

Eros, J. (2011). The career cycle and the second stage of teaching: Implications for policy and professional development. Arts Education Policy Review, 112(2), 65-70. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632913.2011.546683.

Freeman, D. (1989). Teacher training, development, and decision-making: A model of teaching and related strategies for language teacher education. TESOL Quarterly, 23(1), 27-45. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587506.

Glatthorn, A. (1995). Teacher development. In L. Anderson (Ed.), International encyclopedia of teaching and teacher education (pp. 41-57). London, UK: Pergamon Press.

Knowles, M. (1973). The adult learner: A neglected species. Houston, US: Gulf Publishing Company.

Kunter, M., Klusmann, U., Baumert, J., Richter, D., Voss, T., & Hachfeld, A. (2013) Professional competence of teachers: Effective instructional quality and student development. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(3), 805-820. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032583.

Loeb, S. (2008). Teacher quality: Improving teacher quality and distribution. Retrieved from https://cepa.stanford.edu/content/teacher-quality-improving-teacher-quality-and-distribution.

Mizell, H. (2010). Why professional development matters? Oxford, US: Learning Forward.

Murray, A. (2010). Empowering teachers through professional development. English Teaching Forum, 48(1), 2-11.

Pajares, M. F. (1992). Teachers’ beliefs and educational research: Cleaning up a messy construct. Review of Educational Research, 62(3), 307-332. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543062003307.

Potter, T. S., & Badiali, B. J. (2001). Teacher leader. Larchmont, US: Eye on Education.

Richards, J. C. (2010). Competence and performance in language teaching. RELC Journal, 41(2), 101-122. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688210372953.

Rodríguez Bonces, M. (2014). Organizing a professional learning comminuty: A strategy to enhance professional development. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 19(3), 307-319.

Saylag, R. (2012). Self reflection on the teaching practice of English as a second language: Becoming the critically reflective teacher. Procedia: Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, 3847-3851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.06.158.

Tice, J. (2004). Reflectvie teaching: Exploring our own classroom practice. Retrieved from https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/reflective-teaching-exploring-our-own-classroom-practice.

UNESCO. (1990). Innovations and initiatives in teacher education in Asia and the Pacific region (Vol. 1). Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/education/pdf/412_35a.pdf.

UNESCO. (2015). The right to education and the teaching profession. Paris, FR: UNESCO Education Sector.

Villegas-Reimers, E. (2003). Teacher professional development: An international review of the literature. Paris, FR: International Institute for Educational Planning. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0013/001330/133010e.pdf.

Yates, C. (2007). Teacher education policy: International development discourses and the development of teacher education. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0015/001557/155738E.pdf.

Zeichner, K. M., & Tabachnik, B. R. (1999). Participatory development and teacher education reform in Namibia. In K. Zeichner & L. Dahlstrom (Eds.), Democratic teacher education reform in Africa: The case of Namibia. Boulder, US: Westview Press.

The Authors

Alexandra Novozhenina obtained her BA degree from Southern Federal University in Russia and graduated in the Master’s in English didactics program of Universidad de Caldas. She has taught adults, teenagers, and children at English and bi-national centers. She has also been working as an academic supervisor.

Margarita M. López Pinzón holds an MA in English didactics from Universidad de Caldas. She is the director of the master’s program in English didactics at the same university and has been teaching graduate and undergraduate courses. She has been doing educational research and sharing her findings at different events in Colombia.