https://doi.org/10.19183/how.25.1.436

Gabriel Vicente Obando Guerreroa

Ana Clara Sánchez Solarteb

aUniversidad de Nariño, Pasto, Colombia. E-mail: gobando@udenar.edu.co

bUniversidad de Nariño, Pasto, Colombia. E-mail: acsanchez@udenar.edu.co

Received: October 1, 2017. Accepted: November 20, 2017.

How to cite this article (APA 6th ed.):

Obando Guerrero, G. V., & Sánchez Solarte, A. C. (2018). Learners’ satisfaction in two foreign language teacher education programs: Are we doing our homework? HOW, 25(1), 135-155. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.25.1.436.

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. License Deed can be consulted at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

This article reports the results of a descriptive research project whose goal was to identify the degree of satisfaction of students enrolled in two teacher education programs at a public Colombian university. As satisfaction and quality are prevalent terms in curriculum evaluation, and are encouraged by accreditation and government regulations, learner feedback can be valuable input in these processes. Seventy students of beginner, intermediate, and advanced levels from two programs were surveyed. The findings suggest that besides the mechanisms proposed by the government to collect information, student feedback needs to be considered. Regarding the programs, learners display an overall satisfaction, but methodology and assessment need to be considered in future curriculum development and evaluation processes.

Key words: Curriculum evaluation, learner satisfaction, teacher education programs.

Este artículo presenta los resultados de un estudio descriptivo orientado a identificar los niveles de satisfacción de los estudiantes matriculados en programas de licenciatura en una universidad pública en Colombia. Los términos satisfacción y calidad son comunes en evaluación curricular, y son promovidos por la acreditación y por las regulaciones gubernamentales. En estos procesos, la retroalimentación estudiantil es valiosa. Setenta estudiantes de niveles principiante, intermedio y avanzado de dos programas de licenciatura fueron encuestados y los resultados sugieren que los instrumentos propuestos por el gobierno para recoger información se enriquecen con la retroalimentación estudiantil. En los programas hay satisfacción general. Sin embargo, aspectos como metodología y evaluación deben ser considerados en futuros procesos de evaluación y desarrollo curricular.

Palabras clave: evaluación curricular, programas de educación docente, satisfacción estudiantil.

In Colombia, the Ministry of National Education is pushing toward the establishment of Colombia as a bilingual country (Ministerio de Educación Nacional [MEN], 2009). In light of this goal, the ministry has been aggressive in terms of establishing parameters for the institutions offering teacher education programs, for teacher educators, and for future foreign language teachers. The Decree 2450 from December 17, 2015 makes those demands evident, as it sets high standards for new foreign language (L2) teachers in terms of language proficiency (C1 proficiency level according to the Common European Framework of Reference) and the background they should have to become teachers (pedagogy, didactics, methodology, science, and math). Teacher educators are doing their best to keep up with these demands and self-evaluation processes are underway around the country to make adjustments to curricula. So far, and as different authors have debated (M. L. Cárdenas, 2006; R. Cárdenas, Chaves, & Hernández, 2015; R. Cárdenas & Miranda, 2014; González, 2015; Sánchez & Obando, 2008; Usma, 2009), the government’s goal of moving towards becoming a bilingual country (i.e., referring to Spanish and English) has not been as successful as expected. The reasons for this outcome go beyond the responsibility of teacher education programs, and they are yet to be addressed in the country. The perception is that L2 teachers and teacher education programs may be the ones to blame. Does this mean that these programs are not doing their homework? Beyond the limitations of government policies and demands, accreditation results, and Pruebas Saber-Pro1 results (Gómez Sará, 2017), the programs have to reflect on the educational experiences they offer and how satisfied learners are with them. Becoming aware of factors that affect learner satisfaction encourages the agents involved in curricular evaluation (i.e., administrators, teachers, students) to play up their strengths and work on the weaknesses. Today, programs get permanent learner feedback from end of the course evaluations and from meetings with students as part of self-evaluation processes that aim at guaranteeing quality. This feedback goes to government agencies, but, what about explicit feedback on factors that directly affect learners? Do we have detailed information regarding whether foreign language teachers are satisfied with what they have learned, beyond what external agents like the media or the government agencies say? In the case of the two surveyed programs, the answer is no.

This study sought to fill this gap by identifying the degree of learner satisfaction in two accredited foreign teacher education programs, while gaining insight regarding the areas that need work to balance the demands of the government and the satisfaction of the learners. After all, they are the ones who will be facing the real teaching and learning conditions of Colombian classrooms. It is worth mentioning that while learner satisfaction is present in current literature addressing areas like online learning, marketing, blended courses, and classroom organization (Al-Azawei & Lundqvist, 2015; Caruana, La Rocca, & Snehota, 2016; S. Li, 2016; N. Li, Marsh, & Rienties, 2016), studies on foreign language education programs are rather limited.

A variety of elements can come into play in foreign language teacher education programs and the satisfaction learners display towards them. Some of those elements are outlined next.

Schick (as cited in Kiely & Rea-Dickins, 2005) suggested that evaluation can have a political dimension and be used in different ways to: make a program look good (i.e., eyewash evaluation), cover the failure of a preferred program (i.e., whitewash evaluation), sink a disliked program (i.e., submarine evaluation), satisfy a condition of funding (i.e., posture evaluation), or delay the need to act (i.e., postponement evaluation). As suggested before, accreditation processes and evaluations for teacher education programs in Colombia have been encouraged in this decade; it might be inferred that this system aims at reducing the number of existing programs, preventing the permanence of programs that display low quality or improvisation and limiting the number and type of programs offered. That is, a program cannot be opened if its title is not included on the list issued in the Resolution 02041 of February 3, 2016 (MEN, 2016). In preparation for accreditation purposes, or as the result of it, many programs are doing curriculum evaluation, looking into their strengths and getting informed about their weaknesses by asking both internal (i.e., teachers, students, administrators) and external agents (i.e., school principals, employers) about a variety of aspects including resources, instructional processes, and assessment. The evaluation and implementation of changes are underway and the outcomes of the accreditation processes fostered by the government and the modifications implemented in the programs will need further analysis.

Since the purposes of program evaluation are varied, the evaluation can focus on different aspects such as outcomes, syllabi, the theoretical foundations, resources and materials, teaching methods, and teachers and teacher training, among others (Richards, 2017).

R. Cárdenas (2009) characterized foreign language teacher education programs in Colombia, concluding that globally and, to some extent, Colombian programs tend to display four variables around which they educate future teachers. The variables are:2

[a] The attitude towards the teaching profession; [b] the knowledge not only of the subject matter (foreign language and methodology), but also of the specific context, its problems and potentialities; [c] skills to be used immediately and skills allowing professional development beyond formal education; and [d] awareness of the meaning and the responsibility that foreign language teaching entails. (pp. 103-104)

These variables include elements that strengthen a teacher’s identity as a professional (e.g., knowledge of the subject matter) and as an educator (e.g., attitude towards teaching). It might be suggested that if foreign language teacher educator programs find a balance between those variables, learners will have the necessary knowledge and skills to approach teaching effectively and might perceive those programs as satisfactory.

The guide for the self-evaluation of undergraduate programs made by the National Accreditation Council (Consejo Nacional de Acreditación [CNA], 2013) encompasses the abovementioned elements and evaluates the quality of a program depending on how satisfied students, teachers, administrators, employers, and other stakeholders are in terms of (a) the mission of the program, institutional educational project, and program curriculum; (b) students; (c) teachers; (d) academic processes; (e) national and international visibility of the program; (f) research, innovation, and cultural and artistic creation; (g) well-being at an institutional level; (h) organization and administration; (i) alumni and their impact on their context; and (j) facilities and financial resources.

The guide issued by the Colombian ministry for the self-evaluation of undergraduate programs whose goal is to receive accreditation (CNA, 2013) suggests that in self-evaluation and accreditation processes, students can describe their experience regarding how they enter a program, how they participate in activities aimed at providing a wholesome education, and how the academic and student life is regulated. The information collected about these sub-areas allows curricular agents and government stakeholders to get a general picture of how satisfied learners can be in a program agreeing with the idea that program evaluation can focus on students “to find out what they learned from the program, their perceptions of it, and how they participated in it” (Richards, 2017, p. 278).

Macquarie University highlights the importance of student evaluation and feedback stating that they inform the institution and teachers about learning experiences, the effectiveness of instruction, and that both also serve as input for teacher evaluation and curriculum development along with “ensuring that students enjoy high quality learning experience at Macquarie . . . the continual improvement of the unit and program of study that is being offered, and ensuring that the University is achieving the desired standard of quality in students’ learning experiences” (“Student Evaluation and Feedback,” n.d., “Why do we use,” para. 4).

Context

The study focused on two foreign language teacher education programs at a public university in Colombia, one whose emphasis is on English as a foreign language and Spanish as a native language and the other on English and French as foreign languages. Curricula in these programs are organized in four areas: the development of communicative competence, pedagogy, methodology, and research, concurring with the areas outlined by R. Cárdenas (2009) and Fandiño Parra, Bermúdez Jiménez, and Varela Santamaría (2016). The courses that aim at preparing students to become L2 teachers include linguistics, morphology, syntax, semantics, educational psychology, foreign language methodology, and second language acquisition (SLA). Both teacher education programs and the university the programs belong to, have been accredited by the Colombian National Accreditation Council.

Participants

Thirty-three female (age x̄ = 20.3) and thirty-seven male students (age x̄ = 21.3) from two foreign language teaching education programs were chosen using a random sampling by listings. This group included learners at beginner, intermediate, and advanced stages in the program: Eleven students belonged to first semester, six to third semester, fifteen to fourth semester, fourteen to sixth semester, twelve to eighth semester, and twelve to ninth semester.

Type of Research and Design

Both quantitative and qualitative paradigms were used in the study as a way to collect abundant and relevant information about the factors that contribute to learners’ satisfaction. This study displayed a descriptive design, in line with the research purpose, and adhered to the fact that no conditions in the context were intervened.

Data Collection Procedures and Data Analysis

The participants completed an anonymous survey containing 32 items with a five-point Likert scale and one open-ended question. The instrument used (Sánchez Solarte, Obando Guerrero, & Ibarra Santacruz, 2017) was previously administered and proved to be effective in terms of the quantity and quality of the information elicited. The 32 statements covered wide areas that were likely to affect learners’ satisfaction. The questions addressed these areas: course organization (Items 1, 2, 5, 15, 16, 20, 21), students’ performance (Items 6, 7, 8, 10), teacher and students’ interaction (Items 3, 4, 11, 12, 13), assessment practices (Items 14, 17, 18, 19, 21), facilities and resources used (Items 9, 23, 25, 26, 32), and methodology used in the courses (Items 24, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31) (see Appendix). The answers to the closed-ended items were run through a statistics analysis program, the SPSS 24, for frequency and percentages. The responses to the open-ended question were processed with NVivo to facilitate the grouping of data into categories such as class size or classroom management. These categories provided detailed information about factors affecting learners’ satisfaction and pointed at specific ideas to enhance the effectiveness of the programs that could be analyzed in future curriculum evaluation processes.

Quantitative Findings

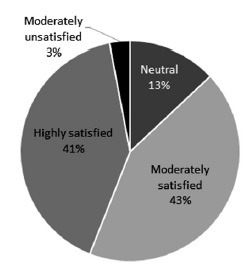

The answers to the closed-ended questions show an overall positive assessment of the courses administered at the moment. Some of the surveyed students provided additional comments about the factors influencing their answers.

As can be seen in Figure 1, the future foreign language teachers feel satisfied with the interaction they have with most teachers in the two programs, describing it as constant, supportive, and open. Learners remarked that this may not be the case for students in other programs. Additionally, being on a separate campus where the Linguistics and Languages Department is located, seeing teachers and students interact in another language, and having access to a specialized library with resources in Spanish, English, French, and even in German, Portuguese, and Italian contribute to a positive learning environment and foster the practice of foreign languages (i.e., English and French).

Figure 1. Teacher-Student Interaction

Figure 2 indicates how the strong trend towards high satisfaction continues in this category. Students indicated they are satisfied with their performance, acknowledging they have adequate support in the program. Classes are perceived as communicative and learners are given ample opportunities to participate in class, which ensures sufficient input and interaction to advance their L2 knowledge. The methodology courses are perceived to be well organized and provide an important foundation for the students’ future professional practice. The environment is conducive to interaction and students have positive feelings towards the institution.

Figure 2. Student Performance

Figure 3 displays students’ overall satisfaction regarding course organization in spite of a visible divergence in the answers. Learners report that due to the university requirements, the courses do follow a consistent organization. They report that most of the teachers discuss their syllabi at the beginning of the semester, as required by the university. Additionally, many teachers start a dialogue with their students and reach agreements on aspects like assessment, strategies, deadlines, and materials, and then come up with a final blueprint for their academic work.

Figure 3. Course Organization

It can be seen in Figure 4 that learners are satisfied as regards facilities and resources, and the bibliography found in the resource center is described as useful and updated. However, learners deem it a necessity to have permanent access to more computers and TV sets in the classrooms. They want to be exposed to different types of media and materials that will increase exposure to meaningful input and bring variety to the lessons as well as to be able to self-access resources whenever they need them.

Figure 4. Facilities and Resources

Learners stated that, in general, the assessment practices fulfill the requirements of the university, but this area is a sensitive one. It had the lowest percentage of learners reporting being highly satisfied, and many informal comments made after the surveys were administered addressed issues related to assessment. These comments had to do with the clarity of the parameters, the contribution of assessment to learning, and the cohesion between class procedures and assessment tasks in all the courses. Some learners explicitly said they were not sure about their perceptions since the regulations for assessment are clear and foster objectivity and a focus on performance, but the real assessment practices were contradictory.

Figure 5. Assessment Practices

In the final category—methodology—diverging views and a tendency towards a moderate satisfaction are observed. Learners are satisfied with classroom procedures, but they state that a negative experience with just one teacher might affect their motivation and even their permanence in the program. Learners suggested that teacher development should be compulsory for all teachers because they notice that teachers with ineffective strategies tend to be the same ones who are not involved in activities such as conferences, research, or advising on graduation papers. The learners explained they want teachers who are role models for them, who show in real life what they have read about teaching.

Figure 6. Methodology

Qualitative Findings

This section summarizes the answers to the open-ended question, “Could you make three suggestions, if any, for the courses to be more effective?” The suggestions provided fall in the categories of Methodology, Assessment, Class contents, and Other factors affecting learner satisfaction.

Methodology. Learners in both programs identified this as an area for improvement. Learners in advanced semesters were very specific about their observations regarding methodology because they had already taken courses related to teacher preparation and they got a better understanding of theoretical foundations and effective teaching practices. Learners were articulate in their ideas and even used terminology belonging to foreign language teaching. The answers are summarized next in sub categories: Teachers’ role, Classroom management, and Classroom activities.

Teachers’ role. Regarding this factor and its influence on learner satisfaction, the students suggested that they observe some variations regarding the role teachers play in the classroom. They stated that while some teachers tend to have an authoritative role and attitude and their teaching goals are clear, others tend to be passive and seem unprepared for the class they are teaching. Learners manifest that this may have an influence on learner motivation, and even though they understand that not all the teachers must have a uniform attitude, they think teachers in the department need to begin a dialogue to establish a common ground and a stable progression in the program. Additionally, some students suggested that sometimes the government decisions need to be discussed and revised, and they would like the teachers in the department to take a stance regarding these issues and interact more with the students regarding aspects like practicum or national language policies.

Classroom management. This area is related to the previous one, but here students discussed the inconvenience of being in a large class. Every year, an average of 60 students are admitted to each program and take most of their classes together. The students are initially divided into two groups and remain separated until fourth semester when it is assumed that the number of students might decrease and the two groups can become one group. Nevertheless, the students stated that the dynamics of the classroom is affected by this in different ways: First, the number of students in the classroom increases dramatically and the groups in advanced semesters can easily have 40 students. Given that the goals of the teaching programs are to prepare future foreign language teachers to be proficient in the L2 and to be skillful in how to teach, class size is an aspect that hinders the achievement of the former goal. When asked specific ways in which class size affected them, some students stated that they could not explain it, but it did. Class size has a negative impact on pedagogical, management-related, and affective dimensions as suggested by LoCastro (2001). In fact, it was acknowledged that teachers attempt to keep the pace of the class to provide communicative activities and to keep everybody participating, but unfortunately, having a large class reduces the learners’ chances to engage in negotiation of meaning and interaction. Students also mentioned that when the two groups come together, they need to start interacting with an entirely new group of people and they might feel less confident to participate or produce output in the L2. They said they sometimes felt observed or judged by their classmates and this might contribute to lower participation in class activities.

Classroom activities. Learners were concerned with the government demands mentioned earlier. Some expressed that in order to reach a C1 level they needed to work hard and be exposed to varied and authentic activities, but that they felt discouraged when the tasks and strategies used by some teachers did not reflect these features. For them, lessons need to be conducted in the foreign language to ensure enough exposure and practice in the L2. They also want teachers to provide classroom exercises similar to those found on standardized tests like TOEFL or FCE since some advanced learners want to pursue graduate studies. The final suggestion they made was to improve the use of the materials. Currently, learners are using two textbooks and feel frustrated when teachers do not follow the book at all or stray from the book contents. They suggest better lesson planning so that all teachers use the textbooks as the main resource in the class in order to guarantee a logical progression between semesters. Advanced learners also pointed out that courses offered by the School of Education could be more specific and oriented towards the topics they encounter when they take the Pruebas Saber Pro (e.g., education policies, legislation, pedagogy) so they are better equipped to address these matters.

Assessment. The comments related to assessment in the teacher education programs mostly have to do with the type and amount of assessment tasks they carry out in the different courses. As mentioned before, students feel that class size affects assessment. Learners feel that in courses related to speaking, they could have more interactive tests, but having to assess forty or more students hinders the quality and amount of feedback. The same happens with courses such as Writing Research Papers, where individual feedback is required. Additionally, it was stated that assessment can be confusing and frustrating due to divergences in the way teachers administer tests, suggesting the need for clear assessment parameters so learners know what is expected of their performance. They added that teachers can enhance assessment and make better use of the available time using resources such as YouTube, Facebook, Moodle, or cell-phones for oral activities because they said that sometimes it is better for them not to speak in front of the whole class. They want assessment to be varied, authentic, demanding, and related to class contents. Finally, learners reiterated that they would like to be exposed, from early semesters in the programs, to exercises based on standardized tests. Learners clarified, however, that they cannot take standardized tests at different times during their stay in the program because standardized tests are expensive, but they could and would like to take mock exams as a way to self-assess their progress.

Class contents. This category is directly related to the multidimensionality of teacher education programs. The learners are aware of the fact that being a teacher is a challenging activity and that these programs must offer courses that cater to learners’ needs. That is, there must be courses focused on the development of communicative competence in English or French along with courses related to the structure of language such as phonetics and phonology or morphology. Finally, the curriculum needs to include courses about research, foreign language methodology, assessment, cultural aspects of language, and second language acquisition. Students see theoretical courses as opportunities for gaining more exposure to the foreign language. Thus, they would like teachers to provide materials in the L2 and use it as a medium of instruction. Outside school they speak Spanish at home and on the street, and they think it is fair that English or French use is compulsory in theoretical courses by the teachers assigned to those courses. Another suggestion regarding content is that courses can be complemented with materials featuring cultural content. Finally, one advanced learner commented that the communicative competence courses and the methodology courses need to be more connected so that learners are constantly reminded that they are in the program to become teachers.

Other factors affecting learner satisfaction. This category encompasses some comments that can enhance the effectiveness of the programs. The first idea is having the same teacher in charge of all the research courses so that there is coherence, cohesiveness, and a sense of progress between them. Another one points out that the classroom tasks in research classes need to be done directly in the language in which they intend to write their project (i.e., Spanish, English, or French).

Increasing tutoring sessions is also suggested since these activities prevent students from falling behind and failing courses. The participants would also like to see tutoring extended to theoretical courses in English, French, and Spanish because they think that the complexity of the topic is what needs to be addressed, not the language proficiency of the students.

One remark that was prevalent has to do with teacher evaluation: Learners expressed their frustration with it because regardless of the answers they provide, changes are not significant. They even said that sometimes they complete the teacher evaluation survey automatically because they do not think teaching practices will be modified by the results of the evaluation. It was added that while teachers who excel should be rewarded, those who do not need follow-up to ensure they improve their performance and make an effort to guide learners to their goals. Specific comments also addressed punctuality, teachers giving them large amounts of work to be handed in the next day, and the language proficiency of some of the teachers. Students commented that they are, in general, satisfied with their preparation for becoming teachers and they think the programs are academically strong. They feel proud of their knowledge, confident with their performance, and expect to be able to teach successfully thanks to the courses they have taken.

The ideas expressed by learners in these two programs relate to their particular learning experience. However, they can also be used to reflect on similar programs around the country and on the factors that affect learner satisfaction.

As suggested earlier, this study intended to collect specific student feedback regarding different factors that might affect learner satisfaction. One main conclusion is that foreign language teacher education programs would benefit from having permanent and detailed information about learner satisfaction. This will allow curricular agents to get acquainted with issues that might be overlooked by relying solely on multiple choice surveys.

A combination of quantitative and qualitative instruments is needed to ensure quality and learner satisfaction in the BA programs. In this study, a generalized degree of satisfaction is perceived among beginner, intermediate, and advanced learners in both programs, and the suggestions provided are similar in the two programs as well, but the specific comments provide a rich source of information that can help teachers and administrators introduce positive changes.

There are no significant differences between programs, or among male and female participants. There is, however, a higher perceived satisfaction among advanced learners. Students in their last year perceive that they are sufficiently equipped to successfully face their responsibilities as teachers in practicum and afterwards.

Learner satisfaction is an area that deserves further exploration and analysis given that teacher education programs cover dissimilar areas that go from communicative competence to research, but they are all interconnected. If one dimension fails, it will affect the others. It is then our responsibility as teachers, researchers, and administrators to listen to the students and try to incorporate those ideas and expectations. The best space to discuss these ideas and come up with tangible strategies is the self-evaluation process that programs undergo permanently.

Being satisfied with a program does not necessarily have to do with having the latest technological resources, high-level classrooms, or numerous native speakers. The surveyed students expressed that satisfaction also comes from elements such as respect, openness, warmth, and honesty in the interaction of the members of the academic community and this is an area that deserves attention. Activities that encourage the strengthening of interpersonal relationships and cooperation need to be permanently fostered.

Advanced learners display more satisfaction than beginner or intermediate learners. This might be due to the fact that they have already taken courses related to methodology, research, and assessment, and they have a better understanding of their role as future teachers.

Learners are satisfied with the development of foreign language proficiency, but it can be improved by implementing technology in the classroom and ensuring that the L2 courses enforce the same standards, organization, and learning experiences. For Rojas (2007) teachers can use resources that allow them to cooperate in a virtual environment, jointly solve pedagogical challenges, and use technology to “help each other, engage in collaborative projects and training, evaluate programs, and discuss possible solutions and future plans. In other words, technology not only facilitates learning and teaching processes, but also fosters professional development and teacher training endeavors” (p. 148).

One important conclusion is that the analyzed programs are perceived as academically strong, organized, and oriented towards providing high-quality preparation for future foreign language teachers. Learners feel confident in their proficiency and teaching skills and feel ready to successfully participate in openings for scholarships, to look for jobs outside the region and the country, to compete for a permanent job in public schools. This is particularly important because, as Akcan (2016) states,

The first few years of teaching are a critical time for professional development (Farrell, 2009; Warford & Reeves, 2003). During this period, novice teachers either strengthen the belief that they will become competent teachers or they leave the profession (Tschannen-Moran & Woolfolk Hoy, 2007). (p. 56)

Public universities and their L2 teacher education programs in Colombia need to keep striving for autonomy because learners do perceive them as effective and satisfying. Despite the sometimes negative external appraisal, universities are aware of their context and of the varied learning experiences future L2 teachers need. Reflective teaching, constant self-evaluation and understanding not only of the government goals but also of learners’ satisfaction, can help future L2 teachers fight what González (2009) calls “standardization, exclusion, inequality, and businessification of their professional development” (p. 185).

Finally, considering the degree of satisfaction reported and the comments made by the participants in this study, it can also be concluded that, in the case of L2 teacher education programs, doing our homework and striving for excellence should involve carrying out research projects, publishing in academic journals, giving lectures and making presentations (both teachers and students) at local and international events.

1A test Colombian students must take in their last year of undergraduate studies in order to graduate.

2Translation made for publication purposes.

Akcan, S. (2016). Novice non-native English teachers’ reflections on their teacher education programmes and their first years of teaching. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 18(1), 55-70. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n1.48608.

Al-Azawei, A., & Lundqvist, K. O. (2015). Learner differences in perceived satisfaction of an online learning: An extension to the technology acceptance model in an Arabic sample. The Electronic Journal of e‐Learning, 13(5), 408‐426.

Cárdenas, M. L. (2006, January). Bilingual Colombia: Are we ready for it? What is needed? Paper presented at the 19th Annual English Australia Education Conference, Perth, Australia. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/238773867_Bilingual_Colombia_Are_we_ready_for_it_What_is_needed.

Cárdenas, R. (2009). Tendencias globales y locales en la formación de docentes de lenguas extranjeras [Global and local trends in foreign language teachers’ formation]. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 14(22), 71-106.

Cárdenas, R., Chaves, O., & Hernández, F. (2015). Implementación del programa nacional de bilingüismo, Cali Colombia: perfiles de los docentes [Implementation of the National Bilingualism Program in Cali, Colombia: Teachers’ profiles described]. Santiago de Cali, CO: Fondo editorial de la Universidad del Valle.

Cárdenas, R., & Miranda, N. (2014). Implementación del programa nacional de bilingüismo: un balance intermedio [Implementation of the National Bilingual Program in Colombia: An interim assessment]. Educación y Educadores, 17(1), 51-67. https://doi.org/10.5294/edu.2014.17.1.3.

Caruana, A., La Rocca, A., & Snehota, I. (2016). Learner satisfaction in marketing simulation games: Antecedents and influencers. Journal of Marketing Education, 38(2), 107-118. https://doi.org/10.1177/0273475316652442.

Consejo Nacional de Acreditación, CNA. (2013). Autoevaluación con fines de acreditación de programas de pregrado (Guía de procedimiento Nº 3) [Procedural guide for the self-evaluation of undergraduate programs with accreditation purposes]. Bogotá, CO: Ministerio de Educación Nacional. Retrieved from http://cms.colombiaaprende.edu.co/static/cache/binaries/articles-186376_guia_autoev_2013.pdf?binary_rand=6331.

Fandiño Parra, Y. J., Bermúdez Jiménez, J., & Varela Santamaría, L. (2016). Formación docente en lengua materna y extranjera: un llamado al desarrollo profesional desde el empoderamiento [Teachers’ education in the mother tongue and foreign languages: A call for the profesional development through empowerment]. Revista Virtual Universidad Católica del Norte, (47), 38-63.

Gómez Sará, M. M. (2017). Review and analysis of the Colombian foreign language bilingualism policies and plans. HOW, 24(1), 139-156. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.24.1.343.

González, A. (2009). On alternative and additional certifications in English language teaching: The case of Colombian EFL teachers’ professional development. Íkala, Revista de Lenguaje y Cultura, 14(22), 184-209.

González, A. (2015). ¿Nos han desplazado? ¿O hemos claudicado? El debilitado papel crítico de universidades públicas y los formadores de docentes en la implementación de la política educativa lingüística del inglés en Colombia [Have we been removed? Or have we given up? The weakened critical role of public universities and teacher educators in implementing linguistic and educational policy regarding English in Colombia]. In K. A. da Silva, M. Mastrella-deAndrade, & C. A. Pereira Filho (Eds.), A formação de professores de línguas: políticas, projetos e parcerias (pp. 33-54). Campinas, BR: Pontes Editores.

Kiely, R., & Rea-Dickins, P. (2005). Program evaluation in language education. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230511224.

LoCastro, V. (2001). Large classes and student learning. TESOL Quarterly, 35(3), 493-496. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588032.

Li, S. (2016). A study of learners’ satisfaction towards college oral English flipped classroom. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 6(10), 1958-1963. https://doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0610.10.

Li, N., Marsh, V., & Rienties, B. (2016). Modelling and managing learner satisfaction: Use of learner feedback to enhance blended and online learning experience. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 14(2), 216-242. https://doi.org/10.1111/dsji.12096.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional, MEN. (2009). Programa Nacional de Bilingüismo: Colombia 2004-2019. Bogotá, CO: Author. Retrieved from http://www.mineducacion.gov.co/1621/articles-132560_recurso_pdf_programa_nacional_bilinguismo.pdf.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional, MEN. (2015). Decreto 2450 [Decree 2450]. Retrieved from http://wp.presidencia.gov.co/sitios/normativa/decretos/2015/Decretos2015/DECRETO%202450%20DEL%2017%20DE%20DICIEMBRE%20DE%202015.pdf.

Ministerio de Educación Nacional, MEN. (2016). Resolución 02041 [Resolution 0241]. Retrieved from https://www.mineducacion.gov.co/1759/articles-356982_recurso_1.pdf.

Rojas, J. (2007). Technology applied to ELT: Reviewing practical uses to enhance English teaching programs. HOW, 14(1), 143-155.

Richards, J. C. (2017). Curriculum development in language teaching (2nd ed.). New York, US: Cambridge University Press.

Sánchez, A., & Obando, G. (2008). Is Colombia ready for “bilingualism”? Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 9, 181-195.

Sánchez Solarte, A. C, Obando Guerrero, G. V., & Ibarra Santacruz, D. (2017). Learners’ perceptions and undergraduate foreign language courses at a Colombian public university. HOW, 24(1), 63-82. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.24.1.310.

Student Evaluation and Feedback. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://staff.mq.edu.au/teaching/evaluation/evaluation_methods/student_feedback/.

Usma, J. (2009). Education and language policy in Colombia: Exploring processes of inclusion, exclusion, and stratification in times of global reform. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 11(1), 123-141.

Gabriel Vicente Obando Guerrero is an associate professor in the Linguistics and Languages Department at Universidad de Nariño (Colombia). He holds a master’s degree in TESOL/Linguistics from the University of Northern Iowa (USA). He is currently enrolled in the PhD program in Foreign and Second Language Education at Florida State University (USA).

Ana Clara Sánchez Solarte holds an MA in TESOL/Linguistics from the University of Northern Iowa (USA). She is the director of the “Lenguaje y Pedagogía” research group at Universidad de Nariño (Colombia). She is currently enrolled in the PhD program in Foreign and Second Language Education at Florida State University (USA).

Sex: Male __ Female __ Age: ___ Semester: ______ Survey number: ______

This survey was designed to gather information related to your experience as a student of the courses offered by the programs in the Linguistics and Languages Department. This information will allow us to determine the degree of satisfaction regarding such courses. The information collected will remain anonymous and will only be used for research purposes. Thank you for your cooperation.

I. Below you will find a series of statements related to different aspects of your experience as a student in the two levels of foreign language courses. Mark with an X the option you consider best describes the degree to which you agree or disagree with each of them.

II. Could you make three suggestions, if any, for the courses to be more effective?

1.

2.

3.